Do I Know You?

I’m an old man—not as old as Robert Frank was when I last saw him, but old. And now that I’m old, most every night an overflow of memories, doubts, regrets, images, and yearnings chew at my brain and keep me from sleeping. Still, come morning, whatever force it is propels me back to work.

My son, Sam, says that I’m a “serial trespasser.” Best I remember, he said this to me when we were wandering around in an off-limits oil field in North Dakota. Or maybe it was after I told him about an incident in Kansas. My friend Les and I were south of Wichita when I asked him to pull the car over. I’d spotted the remains of an old farmhouse on a bluff above the road, and up I went with my camera, only to slide back down ten or fifteen minutes later, disappointed with what I’d found. I was kind of shaky climbing back over the barbed wire, which is why I didn’t hear the pickup pulling up. And that’s how the landowner found me, hooked on the wire. Then he began cursing.

I told him that if I’d come across anyone for miles around, I would’ve asked them about this place, and that really got him going. He reached behind his head for his gun.

“What you’re doin’,” he said, “is snoopin’, snoopin’. You’re snoopin’.”

WILLISTON, NORTH DAKOTA

After the police cleared everybody out of the Walmart parking lot, the parking lot at the Concordia Lutheran Church became the next refuge. You wouldn’t know that the rows of cars and pickups were being lived in but for the blankets hung up to keep gawkers from looking in, and the occasional sight of someone sleeping with their feet out a window.

The job-services office was a short distance from the church. Men and women looking for work began lining up there at five in the morning. Mostly they stood in the dark, nodding hello here and there, smoking cigarettes, stomping their feet to ward off the stiffness and chill.

Back at the church lot, as it began to grow light, people got up out of their cars and pickups and trudged over to the church to use the bathrooms, drank the coffee that was offered to them. If they had jobs to apply for or go to, they headed out.

It was 8:00 a.m. Janice’s husband, a small, mustached, burdened-looking former policeman, had departed an hour earlier for his new job stocking shelves at an Army–Navy store. After feeding and walking their two Chihuahuas, Janice stored clothes, family pictures, knives and forks, and whatever else they couldn’t risk losing in a trunk bolted to the bed of their pickup. Then she set to work combing out her platinum hair, adding a touch of color to her cheeks, penciling in her eyebrows, applying silvery eye shadow, enlarging her already full lips—transforming herself, so as not to look like someone who’s living out of a car.

“My husband,” she said, “treats me like a queen.”

HELENA, ARKANSAS

Helena, Arkansas, had been a freewheeling, anything-goes kind of town, the place to go to gamble, drink, visit a “good-time house,” feel like you’d gotten out from under. Robert Johnson, Sonny Boy Williamson, Sunnyland Slim, Memphis Slim, Roosevelt Sykes—they all played in the juke joints here, in the cafés and dance halls, and hung out plenty too. Sharecroppers left the cotton fields to work there. All that’s left of the old river town now is a kind of nothingness.

I drove back down there thinking that maybe there was something to photograph that I’d missed before, a place that hadn’t been looted, burnt, or knocked down. Ducking in through a broken window, I rummaged around in one of the last buildings left standing on the block.

There was a toilet sticking up out of the collapsing floor, heaps of trash, a mural of a guitar peeling off a wall. I hid when I saw a guy in a pickup coming up the street. It got real quiet after the pickup passed.

On my way back up Highway 1 toward Memphis, I came upon another deserted building. I don’t ask myself anymore why I do such things, just pushed inside. It was like being a scared little kid again, squeezing my eyes closed in the dark, opening them when it got light. The room at the top of the stairs was a jumble of overturned church pews and fallen plaster. There was only one window that, in the darkness, had the look of a TV screen. I caught a glimpse of a small boy streaked with dust squiggling up from under the house trailer across the street. He ran around in an adjoining lot strewn with discarded toys, a seesaw, plastic pails, then down the road. He kept running until a boy, who looked to be his older brother, took off after him.

By the time I made my way back down the stairs, the two of them were waiting for me. The older boy—he was seven or eight—wanted to know what I was doing. I explained that I was a photographer, and that I liked to take pictures of old buildings. The younger boy asked if I would take his picture. “Please,” he said. I looked around for their mom or dad, for someone to talk to, aware of how I’d look to anyone passing by—a bony old guy, dusty, sweaty, carrying a shiny camera, with a car close by.

As I turned to cross the street, the older boy pressed in close and put both his arms around me. He asked me to give him a hug. “I want a hug too,” the younger boy said. I tried to push them away, but they hung onto me, looked up at me, smiling, as if I were someone they knew.

EARLE, ARKANSAS

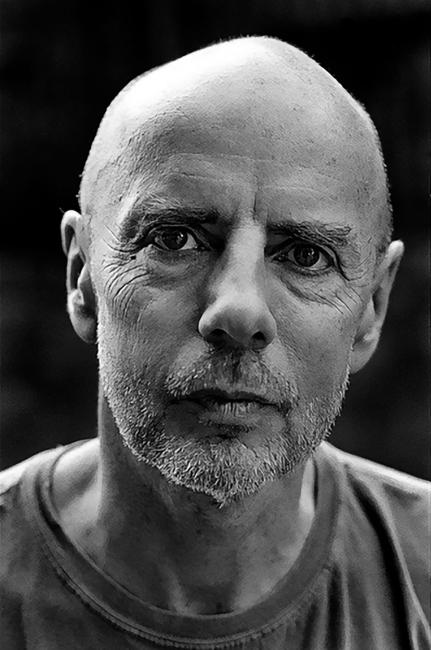

Not having stopped by in a couple of weeks, I hugged Sandra hello, tapped David on his bald head, asked if they’d seen Tim. They pointed to the kitchen at the back of the apartment where Tim Way was sitting, finishing a pencil sketch of a lacy dress with embroidered flowers at the hip. It was a pretty enough dress, I suppose, though not nearly as dramatic as the bejeweled turbans and caftans he wears around town every day.

There’d always been a kind of teasing in Tim’s and my relationship. But that morning there was a hint of worry in his eyes. “I’ve got to apologize,” he said.

“Apologize? For what?”

“I was talking to the lady who lives across the street and told her that you’re a photographer from New York. And she got to telling me about her granddaughter, Mikey. Mikey’s getting married and would like to have some pictures of the wedding, but doesn’t have the money for them. So the lady asked me if I would ask you if you’d take the pictures.”

Suddenly feeling a bit put upon—I didn’t even know these people—I cut Tim a nasty look. He covered his mouth with his hand, the way he does when he’s embarrassed or hurt. “It’s no big thing,” he said. “Just isn’t.”

Mikey nodded hello when I walked into the chapel, while her mother began to order me about. “Get some good pictures of the wedding gown…get Mikey putting on her makeup…get the flower girls…make sure you get Mikey walking down the aisle with her grandmother.” I did manage to break away before things really got going to ask Mikey if there were any pictures that she might want me to take.

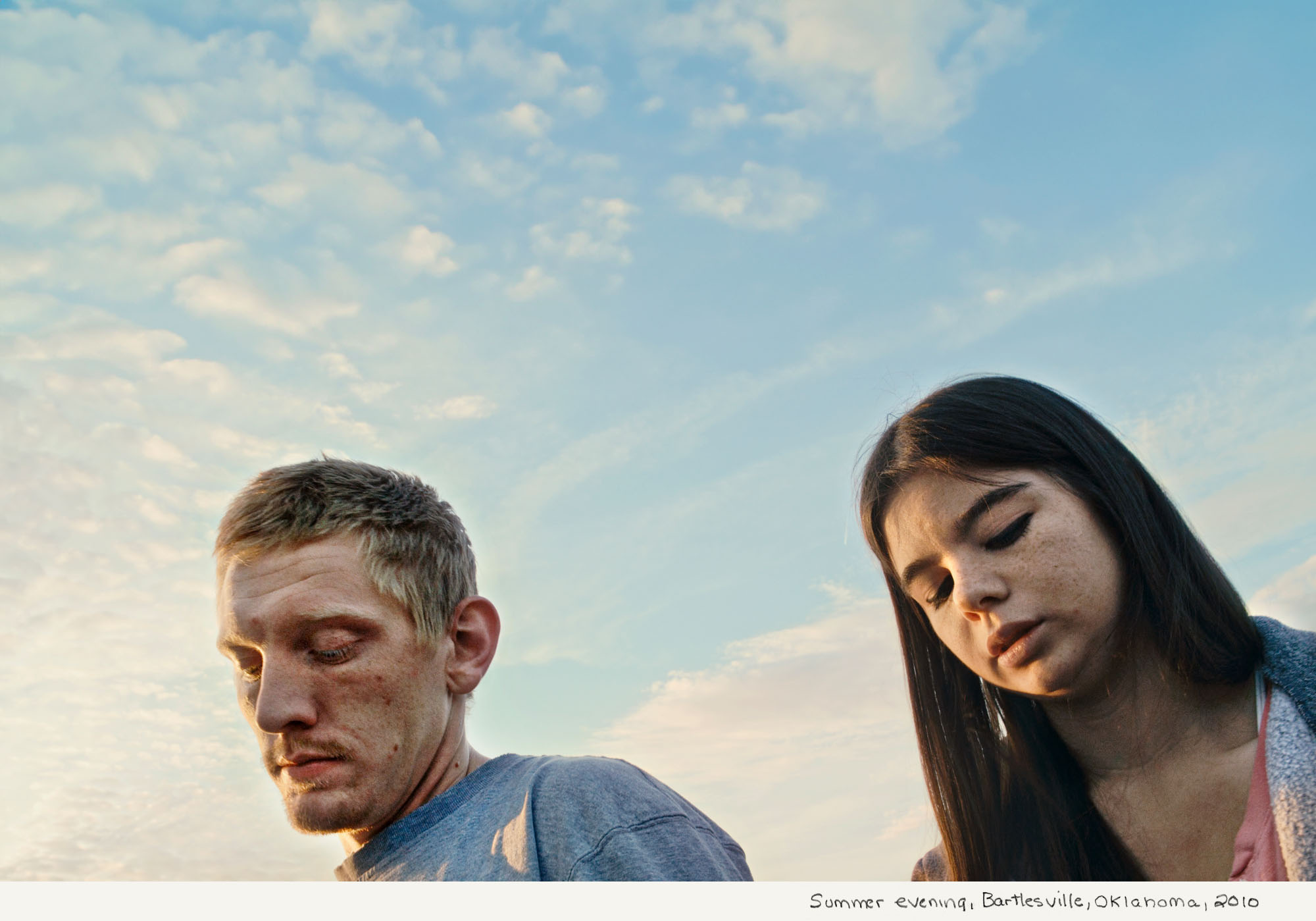

Looking dour and tense, she told me that what she wanted most was a picture of her fiancé, Ethan, waiting outside the chapel for the service to begin.

“I want to see him nervous, smoking a cigarette. That’s how I want him.”

TIOGA, NORTH DAKOTA

I drove up to Tioga for their Fourth of July celebration. I’d never been there before, but walking around, you had to think that, appearance-wise anyway, the place was a stand-in for most any small, upper-Midwest town.

It was hot, the parade delayed. Elderly people fell asleep in their folding chairs, kids cried to go to the bathroom. I was starting to feel that there were better things to do when there was some movement on the horizon, the glitter of sequins, sunlight reflecting off a windshield.

Finally, the parade started down the street: police cars sounding their sirens, a pickup sailing an American flag, American Legionnaires, Veterans of Foreign Wars, a fire engine, baton twirlers, antique cars, horse-drawn wagons, Boy Scouts, beauty queens, brass bands. People placed their hands over their hearts when they heard the national anthem.

The boy I photographed at the fairgrounds that afternoon was like a cherub, his face so pink from the sun he could have been on fire. I spoke with his father, to be sure that my taking pictures was okay with him, then asked for the boy’s name. Luke. Luke was five. Meanwhile, I didn’t want to interrupt the old soldier near us. I’d caught a glimpse of retired Sargeant Halvorsen during the parade, a little lost-looking in the back seat of a convertible. Now he was the center of attention. He was pointing to the Bronze Star, Silver Star, and other military decorations he’d earned in combat during World War II, trying to explain the significance of each of them. You could tell that the young people leaning in to hear him couldn’t quite comprehend the gravity of what he was saying. Still, he kept talking.

It was late in the day. I was trying to find my car, when I walked past a barrel filled with torn, crumpled-up, faded American flags. The flags had been taken out of service and were being disposed of according to protocol. Still, there was this ominous, anarchistic feel to watching them burn.

Eugene Richards is an award-winning photographer and filmmaker. His films include Thy Kingdom Come (2018 Atlanta Film Festival Jury Award finalist) and But, The Day Came (2000 New York Expo of Short Film winner, documentary). Richards is the recipient of the W. Eugene Smith Memorial Award, a Guggenheim Fellowship...