Beauty Is the Only Language Worth Speaking

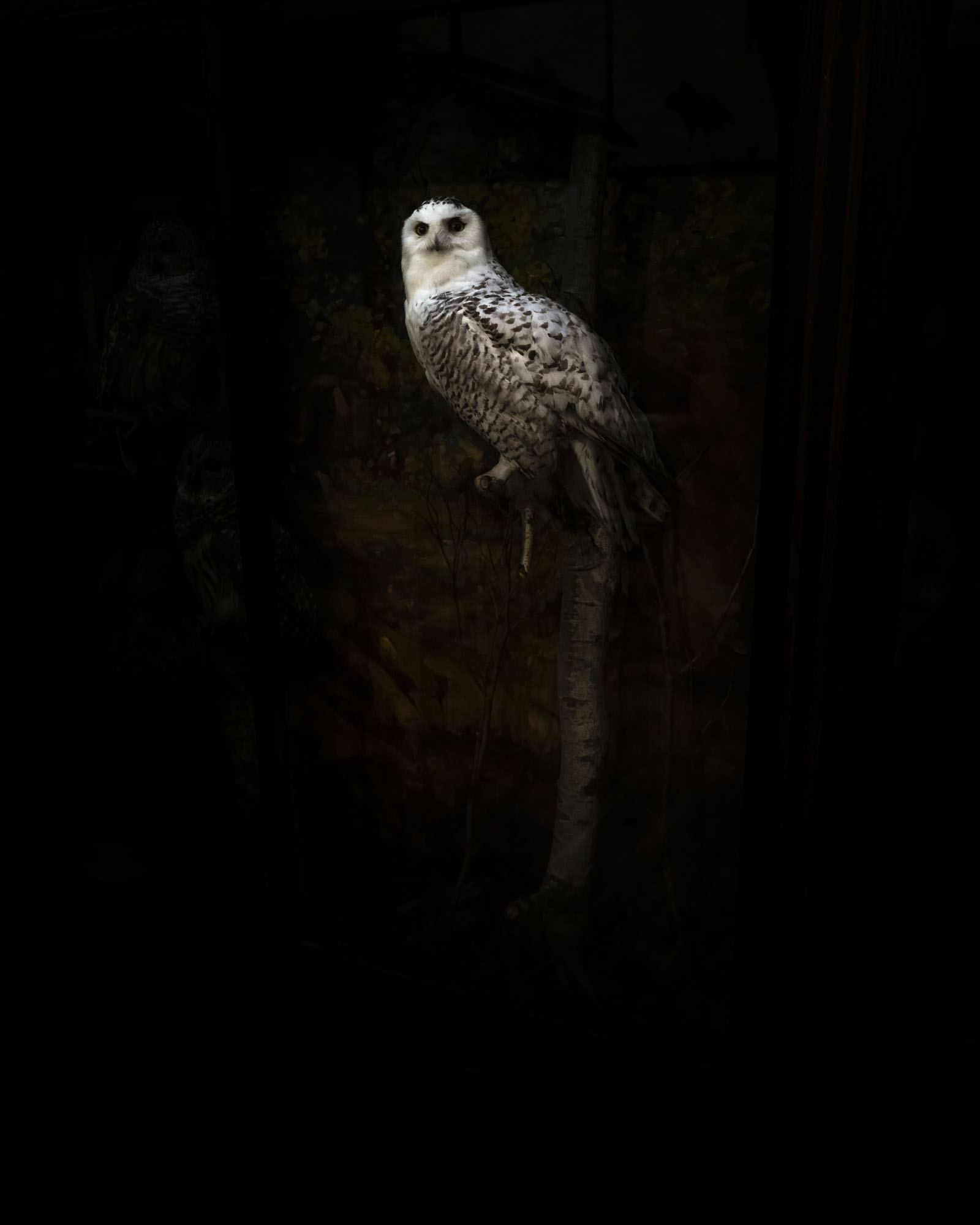

Deep inside our eyes, next to the dark velvet lake of the aqua vitreous, are cones and rods. The rods allow us to see in the gloaming, but only in grayscale. The cones are responsible for color, but they need light to work.

The camera sees things differently than our eyes do. This is the reason photographing at night is so addictive. The camera becomes the youthful eye. The camera is an owl. We are shown something outside of typical human perception.

We have three types of cone receptors in each eye: red, green, and blue. If you stare at a slice of red velvet cake for one minute and then look at a white wall, you will see that cake projected in a verdant bluish green. This is because your red cones are now exhausted. Certain animals have more cone receptors than humans do and can see well beyond our red-to-violet light spectrum. Butterflies have at least five kinds of cones. Mantis shrimp have as many as sixteen. This means that a mantis shrimp—an animal that lives in the shallows, not the deep—has the potential to see millions more variants of colors than humans do. Mantis shrimp practically speak color. A few people, primarily women, have four types of cones. These women are tetrachromats, so seeing color is one of their many superpowers. But some people, primarily men, only have two cone variations, making them blind to the color they are missing. If you are missing red, then a juicy strawberry appears beige. No wonder some men overcompensate.

We see color in two ways. Seeing the color in a rainbow or TV screen is the result of wavelengths of light coming straight and uninterrupted to the eye. But when we see something red, like a ruby, it is because all the other colors have been absorbed by its most basic structure, its atoms, and red—its ruby-ness—has been spat back out for us to see. It’s counterintuitive, but a forest is only green because it refuses its greenness. A peach is only peach because it will not soak up that orangey-yellow, pushing it out to the world and keeping all the other colors absorbed safely inside. The overflow of that peach color is called scattering. This seeping out helps us discern the depth, texture, and shape of things, the roundness of the circle, the silkiness of the silk.

Color resists logic. Color is more like magic. Matisse said, “With color one obtains an energy that seems to stem from witchcraft.” People go to extremes to replicate color in the forms of dyes and paints, or to possess color in the form of gems and precious stones. To live without color is like watching the symphony on mute. Imagine living under a colorless sky. Achilles wept for two reasons: His feet hurt, and the sky and ocean were the same endless, dull hue. Isaac Newton must have been obsessed with blue and divided almost half the visible light spectrum into its three variants: blue, indigo, and violet. Many scientists now believe that indigo doesn’t have enough wavelengths to warrant being its own color, and so indigo, like the planet Pluto, is about to be pink-slipped.

I can no longer see as I used to. Three years ago, my eyesight began to change. The precision of a royal-blue pen, the decisive moment on the page, now just lines and shapes. Camera controls organized by touch, four twists left for a sixtieth of a second, five clicks to the right for F2.8.

At the optician, I stare into a bunch of machines that hiss, spit, and flash. After thirty minutes, he tells me that I’m fine, just getting older, and I leave the office with a prescription for reading glasses.

I take the back roads home in the dappled-late-afternoon-anything-is-possible light—a flickering strobe of sunlight that, for a brief moment, gives me back my youth. Flashes of greens, orange, blues, blacks, yellow—a color continuum of time, light, and space. Driving through that emerald tunnel of summertime, with its smell of pines, past the black holes of lakes, into the infinite blue sky, I’m thirty-one again at full throttle in a skiff across the harbor; twenty-five drinking a beer in the back of a pickup; seventeen, cruising the Chagford road across the moors in Devon. My right shoulder doesn’t ache. I don’t need readers. There’s nowhere to be. No responsibility. I am free and limitless.

In that light, I feel my relationship with sight—especially with color—grow more desperate. My work has become an urgent call to live, a primal roar telling me not to waste a second, to be here now.

Look at this. Experience this. Feel this.

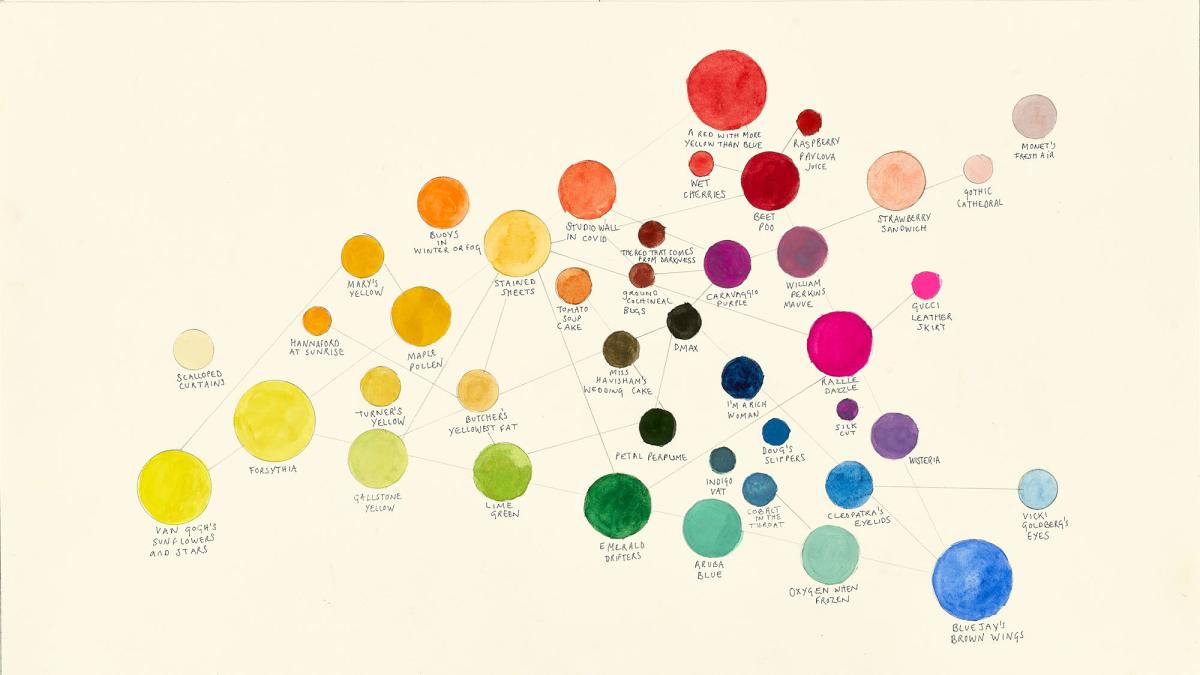

Time is the only currency. A birthday remembered by five red cherries wet on a pale pink tablecloth. A trip to Russia mapped in light coming through thin yellow scalloped curtains. A series of multicolored cakes memorializing a woman who loved to live. I want you to have the same experience with this collection of pictures as I had when I first found the images—the feeling in the body that comes with bearing witness to something rare.

In the time it took to write this sentence, somebody died, somebody was born, a language disappeared, a forest fire began, an insect was crushed, an idea inched forward. When I am dying, I want to think of the bounty of an orchard, a tree laden with one thousand apples, rosso corsa, and bees abounding.

Earlier this year, in a discussion about my work, a friend told me I had dedicated my life to something that doesn’t exist. He said, “Color isn’t real; it’s just our brains’ interpretation of light wavelengths.”

I have been annoyed ever since.

There is a twenty-by-eight-foot wall in my home studio, and I paint it the color I want to be surrounded by, the color I need in my pictures, the color I want my body to absorb and reflect—a color that clashes or balances my outfits, skin, and mood.

The paint gets thicker and thicker each year. By the end of my life, the wall will be out into the middle of the room, the years cataloged and marked. We can never move.

When I was pregnant, I painted the wall a soft pink to match my baby, but it felt too sweet: It wasn’t the rope I needed to pull me through the monotony of the first year of parenting. I kept adding darker and darker shades of pink until I ended up with Benjamin Moore’s violent magenta Razzle Dazzle.

The following winter, I painted the wall gold, folded one hundred paper cranes, and pinned them in a V-shape flying south.

Six months later, I painted the wall silver, hung a disco ball in the window, and wrote short staccato sentences about time in a 2H pencil every morning.

As summer ended, I painted the wall a teal green (misnamed Aruba Blue) to match a dead cormorant I had found in the middle of the road. I arranged it in front of the green—a still life. Scout, then a toddler, shushed me, pointer finger to lips, and whispered, “Why is the birdie always sleeping?” Cormorants are one of the only birds whose wings become waterlogged to help them dive deeper, so they must dry their wings at dusk, a sight that chokes me every time.

After that green, I decided to paint the wall a deep sapphire blue because sitting in front of that color makes me feel like a rich woman. (I usually only feel that rich when I have a box of forty Tampax, a case of Spindrifts—preferably pineapple—a pack of AA batteries, a book of stamps, an E-ZPass, and a full tank of gas.)

A few years later, after my best friend Mary died, I painted the wall her favorite color—a shade of warm saffron that will always be—Mary’s Yellow. I would lean my cheek against that color to soothe myself when I couldn’t stop crying.

Color is a balm.

The year COVID hit, I dripped an orangey-red paint all over the walls and floor to make the room a vibrant tomato womb. I dragged my computer in front of it and started to dress only in pink, so the screen lit up like a beating heart on my daily Zooms.

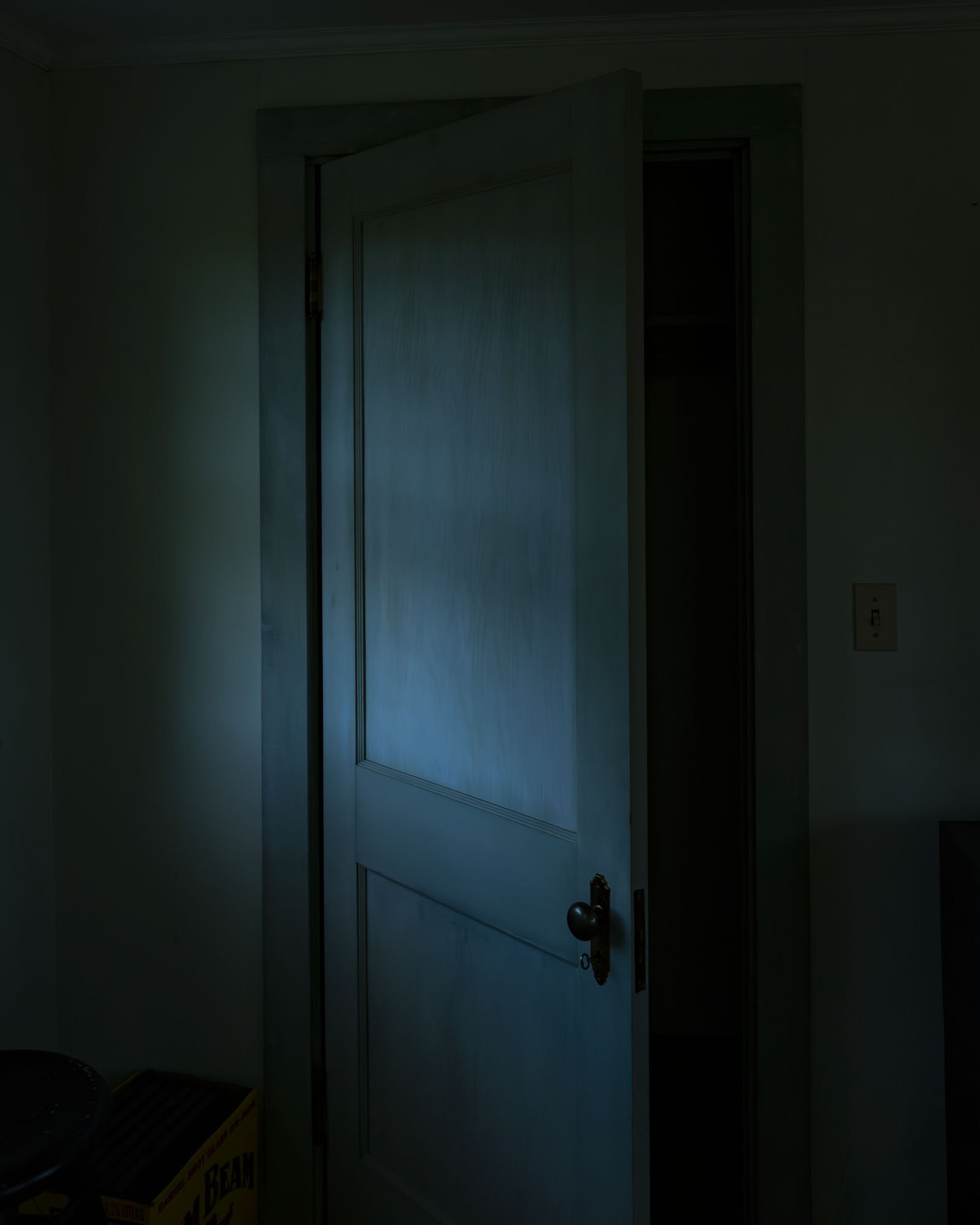

And last winter, obsessed with Flemish eighteenth-century still lifes, I painted the wall a rich plum, but it dried to black. Each word I wrote became more and more internal until I was underground, digging deeper and deeper into the dark.

Cig Harvey is a fine-art photographer and writer whose photographs and books appear in the permanent collections of museums such as the Library of Congress (New York), Museum of Fine Arts (Boston), Philadelphia Museum of Art, and more. Her latest book, Emerald Drifters (Monacelli, 2025), explores a life through color.