Splitting the Family Story

The plastic sandwich baggie in my ex-husband’s hand was scalloped in fog; all I could see of what was inside was a folded paper towel and some dirt. The Long Island summer heat wafted up from the gravel in waves. Even though we were shaded by the canopy of my neighbor’s chestnut tree, we could still feel the sun. The children ran around us in lazy figure eights, stretching their legs after the long drive. My ex’s pickup truck clicked and popped next to us as it cooled. He thrust the bag at me like a bouquet.

We stood a few feet apart as we spoke; I stretched my arm out to receive the bag, keeping my feet planted. I was surprised at its coolness and prodded whatever was folded into the paper towel gingerly with my fingertips through the plastic. I could feel two hard knots, each the size of a stone. We both took a step backward.

“It’s garlic,” he explained. “From the garden.” We both knew which garden he meant. His sister saved some bulbs the last time she visited our farmhouse in rural Pennsylvania. She’d planned to plant them in her back yard in Michigan, but never got around to it. He’d just taken the kids on a road trip to visit her there and she’d given him the cloves that she’d kept in cold storage. He tucked the baggie in a cooler in the back of the pickup truck for the twelve-hour drive home.

He nodded to a small two-by-ten plot next to the front door of my apartment that I’d tried to turn into a garden. Scarlet runner beans climbed a trellis of bamboo stakes and sunflowers taller than the kids swayed happily at the edge. A purple milkweed plant that a man had brought me as a gift on our second (and last) date exploded messily between them.

The children’s loops slowed and they began to tussle. It had been a long ride and their father still had another hour between us and his own apartment in Brooklyn. “Thank you,” I told him, holding the baggie up again between us. And meant it.

He shrugged and turned back to the car, accepting sweaty hugs from the boys before climbing back into the driver’s seat. As the engine roared to life and the children ran toward my apartment door, eager for some cold water and cartoons on the couch, I stood at the end of my driveway and watched him three-point turn out of the dead end and drive down the street. We didn’t wave. I don’t think he looked back.

Fifteen years earlier, after we were married but before we had children, we’d also taken a road trip, this one from our apartment in New York up to the Gatineau Hills in Quebec to visit my then-husband’s old professor and mentor—a very talented and very gruff painter—and his second wife, a much younger professor of accounting named Mary Anne.

Each day during our stay there, my husband and his professor would pack their travel easels and drive out into the Ottawa Valley to paint landscapes. Each evening, we would go to boozy dinner parties with older academics and artists who summered in the area.

One night, gathered for a party at another couple’s home, Mary Anne obsessed over the invisible fence that kept the couple’s pair of standard poodles on the property. The guests were sitting outside in the dark at a picnic table still set with the remainders of our roast-chicken dinner, and the fireflies were out. We’d all had plenty to drink, so no one was quick enough to stop Mary Anne when she whipped off one of the dog’s collars and snapped it around her own neck. Her bob glowed in the moonlight, getting smaller and smaller, her little white head bounding through the field like the lifted tail of a doe. Eventually, her head dropped from sight. Later she’d explain that when she hit the line of invisible fence, she’d expected a small jolt. Instead, the shock felt like her body had been short-circuited—not hurt, necessarily, just sent somewhere a bit far away, as if the current had reset something and she was just coming back online.

Mary Anne was fun—unpredictable and wild. She’d speak as easily about the Group of Seven as she would the GDP of Ireland. At sixty, she was twenty years younger than her husband. Her energy reminded me of a dam about to burst—full to the brim, curious and uninhibited. She couldn’t sit still and her cheeks were pink without makeup. I remember feeling older than her, even though I was half her age at the time.

The two of us stayed in the house together during the day while the men painted. Sometimes we’d play cards on the back deck. I would read, mostly, and ask her questions about how to be an artist’s wife, a role whose weight I was only beginning to understand. Every wall of the house held a painting by her husband. When she invited the wife of another artist over for lunch, I perched on the edge of their conversation, listening and learning, as they talked about collectors and dealers and disappointments, their husbands like glass houses they had to protect and shine up. There was a camaraderie between them, an exhaustion and sense of duty, as if they were wartime nurses. They believed in their work as artists’ wives, but still looked at me a little sorrowfully for what I was getting myself into.

On our last day, Mary Anne’s husband stayed in bed, worn out from all the hiking and outdoor painting. Mary Anne and I found our way to the kitchen at lunchtime like usual, with my husband joining us at the small table. Mary Anne decided to cook for us. She’d made clear that week that she was not a cook—we’d usually just grabbed sandwiches from town or picked at leftovers in the fridge—but she rustled around in the pantry and was soon heating up some butter in a pan. She pulled some garlic out of a paper bag beneath the sink.

“This is the last of my father’s garlic from his garden,” she said matter-of-factly. He’d died the year before and she’d taken his death hard; her depression since his funeral was something we’d talked about over the last week. It was why she was drinking so much, she said. It was why she’d run at that invisible fence with the dog collar on—she was just trying to feel something again. While she talked, she chopped the garlic, fried it lightly in the pan, then layered the browned slices inside two grilled cheeses. This combination was a surprise to me, and it was magnificent. She asked if we could taste the difference in the garlic from his garden, how it was nothing like what you could buy at the store. I realized then that she wasn’t eating. “Don’t you want some?” I asked, offering her the half I hadn’t eaten. “You said this was the last of it?”

But she was looking out the window over the sink at the hills.

“I can’t eat it,” she said. “If you don’t, it’ll just rot under the sink.”

My husband’s plate was already empty; he was busily finishing his last bite. I looked out the sliding glass door to the hills that Mary Anne was watching, could see the summer light hitting the tops of a few trees already starting to turn red. I picked up the second half of my sandwich and began to eat.

Part of the lily family, garlic’s botanical name is allium sativum, though across its four-thousand-year-long cultivation history it has been called many things, from Stinking Rose to Nectar of the Gods. Most of the names refer to the plant’s medicinal properties and its accessibility: Camphor of the Poor, Churl’s Treacle, Poor Man’s Treacle. Treacle does not refer to the dark syrup, as I initially assumed. It comes from the Latin theriac, or “antidote,” in this case, most often for an animal bite. Poor Man’s Treacle, then, translates to “Poor Man’s Medicine.” Churl simply means “peasant” or “common man” in Middle English, essentially translating to “Man’s Medicine.”

The churl’s assumptions were proven by Louis Pasteur in the mid-nineteenth century when he scientifically demonstrated the antibacterial properties of garlic. The clove must be chopped, crushed, or bitten to result in the production of allicin, an antimicrobial compound often compared to penicillin. It must be destroyed or sacrificed, in other words, for its healing properties to be released. Maybe Mary Anne inherently knew this. Maybe this is why she chose to serve her father’s last cloves to us rather than return them to the ground. Or maybe she just felt it more fitting for her father’s garden to die with him.

As a kid, I used to love eating shrimp. But one day, I thought too long about it, looked at my order of battered butterfly shrimp and thought, This is taking six lives. Chicken wings seem horrible in much the same way. Every plate brings the vision of half a dozen chickens running around in a panic, wingless bodies skittering without balance.

The math of garlic feels similar to me. When we eat a clove of garlic, we are eating its bulb as well. Every clove is a choice: Plant it and regenerate life, or eat it and that life cycle is over.

A year or two after Mary Anne’s grilled cheese, we moved to rural Pennsylvania and cleared a patch of land in front of our farmhouse for a garden. The soil was sandy and full of rocks, and the large plot enjoyed full sun. I ordered packets from seed companies: lemon cucumbers, jewel- toned rainbow chard, Top Hat sweet corn. Year after year, the animals, droughts, floods, or our busy schedules would decimate the rows. We’d forget to water or a groundhog would snap the cornstalks in half and feast. Only two plants grew reliably: zucchini, in a wild mash of yellow trumpets and green goose-necked fruit whose abundance I learned to hate, and garlic.

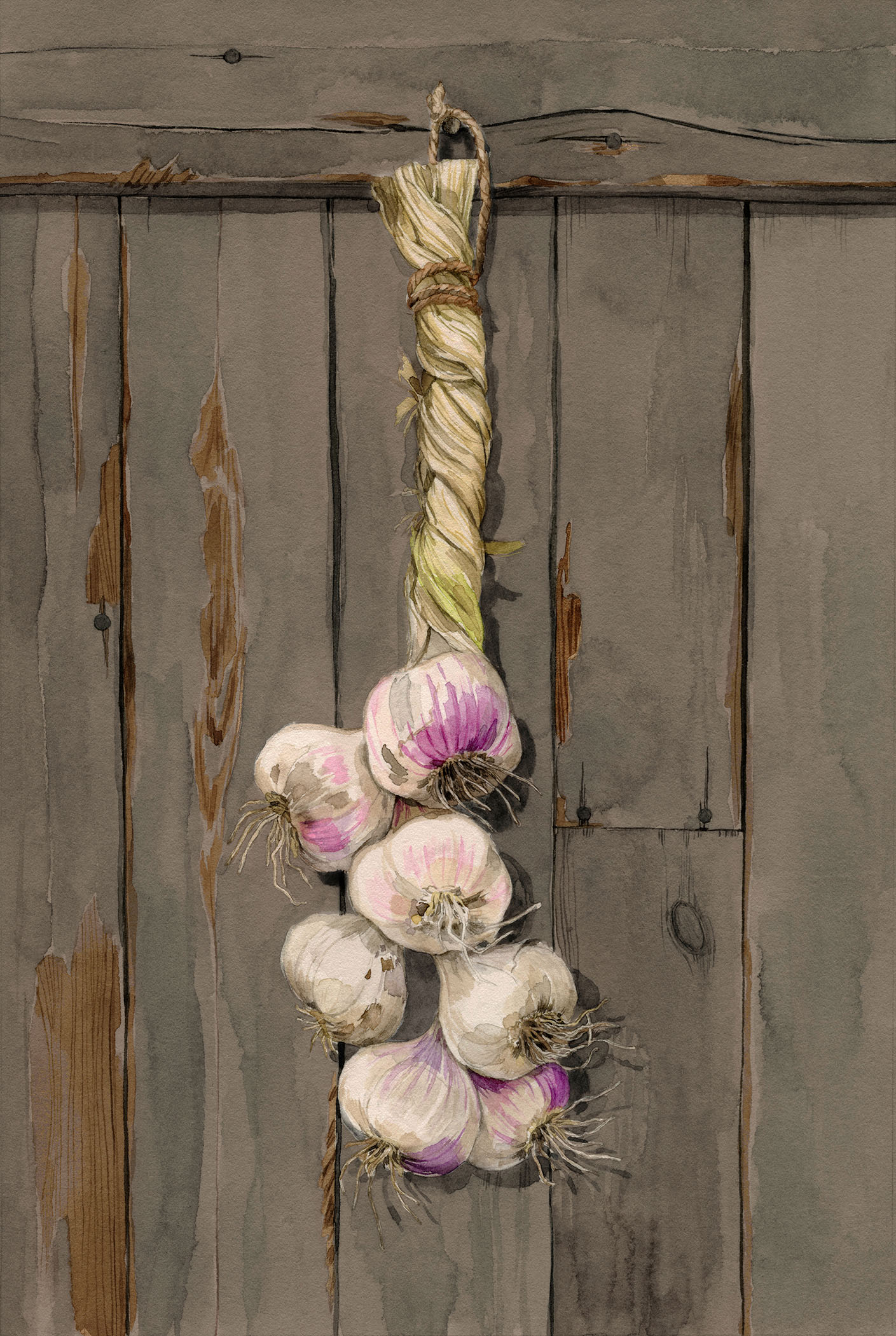

We started with one row and that led to another, and another. Garlic is one of the few deer-resistant vegetables. Each fall, the small barn falling down to one side of the house was strung up with garlands of drying heads. Quickly, we had enough to last us year-round. Soon, we had enough to give away.

Not much about our life at the farmhouse turned out the way we had imagined or hoped. But garlic we were very good at.

We used the Plant Hardiness Zone Map to understand what and when to plant in our region. The map is updated periodically, accounting for the constant warming of the earth. There were eleven zones painted across the map when we first started growing garlic. In 2012, two new zones were introduced, though the northeast corner of Pennsylvania—our corner—hung onto its 5b designation even as the rest of the state crossed into the warmer 6 category. According to The Old Farmer’s Almanac, the best zones for growing hard-necked garlic are in the 3–5 range, since the bulbs thrive in cold. It is still possible to grow garlic in warmer zones, though it gets a bit trickier. In Pennsylvania, we’d plant the garlic in October, often digging as the season’s first snow would lightly fall. Then we’d cover the patch with hay and wait.

In late spring, the garlic’s small green shoots would poke through the bed of hay. As I looked out over the garden from the hill above, the uniformity of the rows reminded me of looking out at a classroom of eager students, each with a single hand raised. We planted hard-necked varieties, which send up slender scapes from their shoots around the summer solstice. Scapes act like periscope scouts, searching for information about the above-ground world, absorbing sunlight for photosynthesis. After a short while, they curlicue into themselves. At this point, they can be snipped off and cooked, their scouting job complete. Any left behind will straighten back up and produce a spiny purple flower. Cutting the scapes as soon as they curl allows the plants to return all their energy into the bulb below the surface.

Usually, we’d harvest by July or August—about a nine-month growing cycle. Even though we harvested the garlic year after year, we still consulted The Old Farmer’s Almanac and googled timing and tools, just to be sure. I am a researcher, a planner by nature. When I was pregnant with my first son, I spent weeks on my ten-page birth plan, detailing my preferred lighting and range of movement, who was allowed in the room. I did not want my baby’s umbilical cord to be cut immediately, preferring him to be placed on my chest for skin-to-skin contact first. A friend had saved her placenta, burying the iron-rich mass in her garden, and I was still debating whether to include that request in my plan when my contractions started more than a month early. My labor was so fast that by the time the anesthesiologist showed up to assess me for an epidural, I was already wrapped in a foil blanket, shaking from shock with my baby under heat lamps next to me, my birth plan at home on my hard drive.

When we eat a clove of garlic, we are eating its bulb as well. Every clove is a choice: plant it and regenerate life, or eat it and that life cycle is over.

I liked the slow, ritual harvesting of the garlic because it was the opposite of my birthing experience; I enjoyed imagining myself as a kind of garlic midwife. In the same way that I knew—from research, from sonograms, from intuition—what my son would look like when he emerged that day, I knew our garlic would likely look like last year’s, since that’s where the planting cloves came from. We’d drag them out of the earth and hold them up in the air, dangling in front of us as we assess their heartiness. When first pulled from the ground, the skin of a garlic bulb is translucent white, soft and fleshy; if you press your fingernail into the skin of new garlic, it feels more like a plum. The bulbs need to be cured, hung up by their hair, dozens of shrunken heads strung up in the beams of the barn by their ropy braids until that soft baby skin wrinkles into a tough papery husk. An entire life in one season.

That final year in Pennsylvania, I left my husband before the garlic was ready to pull, before the rhubarb’s stalks turned fuchsia, and before the soft fronds of fern unfurled around the tree stump where we’d all carved our initials. That last batch of unharvested garlic haunted me. Dreaming of garlic, dream dictionaries told me, means you will uncover a secret. In ancient Greece, midwives hung garlic cloves in birthing rooms to ward off the evil eye. The Greeks also placed garlic on piles of stones at crossroads as supper for Hecate, a goddess associated with childbirth, crossroads, and wilderness. They hoped she might guide evil spirits in the wrong direction as they approached the town, sending the spirits away from their homes, from their children. And then, of course, there are the vampire stories. Birth, secrets, crossroads, protection: That’s a lot of power assigned to a small sachet of stink. We’ve been telling these stories for so long now, and yet so little about humans and our appetites has changed.

I didn’t know what to do with the garlic he had given us. My children don’t like garlic. It felt wrong to eat it myself, much less share it with my new partner. If we ingested this garlic, would we carry around some slice of that doomed Pennsylvania garden’s story with us forever? Part of me wanted the garlic bulbs to spoil on their own, to spare me the misery of choosing what to do with them. So I left the bag in the fridge, tucked behind a bottle of ketchup.

Stepfamilies are not a modern construct. In an essay about the trope of the wicked stepmother, Hilary Mantel reminds us that these familial structures date back to the time of fairy tales when maternal mortality rates were high, and a widower would mourn for a bit and then quickly take a new wife. “If the houses in fairytales are ever orderly, neat and safe,” she writes, “it is a momentary illusion; you may be sure there is a nasty surprise lurking.”

Fairy tales are where I first learned that mothers and fathers, natural and step, are often wicked. In The Juniper Tree, after a man’s beloved wife dies and leaves father and son on their own, he finds a new wife who swiftly sets about murdering her new stepson, then cooks him up for family dinner. Mantel points out that the “father devours his own son with relish.” Hansel and Gretel are abandoned in a forest. Snow White’s stepmother attempts her murder many times. “Step-parenting,” Mantel writes, “with its grudges and feuds over rights and inheritance, was a fact of life through the ages, and now, because of frequent divorce, has become a fact of life again.”

Birth, parenting, splitting, and stepparenting all require a kind of death in exchange for new beginnings. Before soap operas or Grimm’s fairy tales we had mythology: Hera, Poseidon, Hades, Hestia, and Demeter all spent their first years in their father Kronos’s belly because he’d heard a prophecy that one of his children would dethrone him. Only because his mother handed Kronos a stone wrapped in a blanket to swallow in his stead did Zeus escape the same fate. Of course, the prophecy was right. Zeus lived to rule the skies after sending his father to the pits of Tartarus.

Autumn came and went. The sunflowers’ faces grew brown and shaggy. The milkweed went from purple to puffy lace. The last few runner beans twisted and turned to small husks. And my new partner and I decided to move in together.

We found a house closer to my boys’ school. The garlic was the last thing I packed; the plastic baggie made the trip inside a shoebox of other fragile things, like my journals and my grandmother’s vase painted with forget-me-nots. We moved in July, too early to plant the cloves in the garden, so I stuck the garlic in our new fridge, this time behind a bottle of my partner’s capers. There were still places for secrets, even though the boys were growing taller and we now shared the space with another man.

That first summer with the new garden was mostly spent getting to know the plants already there. Our property came with a wall of thick skip laurel overlooking a small patch of strawberries and sorel. The soil was dry and the spot sunny, perfect for garlic. I watched October tick down on the calendar until the eve of Halloween. I waited until I was alone in the house and shook out the garlic from its bag. Bright-green legs sprang out of both cloves, which remained, somehow, white and crisp looking.

Was this some kind of ghost garlic? I wondered. A zombie superstrain that had special powers of preservation? Seed bulbs could keep up to a year, but two years? Possibly three? I understood that even if they looked just fine, they likely wouldn’t produce once in the ground. They weren’t, after all, magic beans.

I planted them anyway. I didn’t prep the soil. I didn’t aerate or fertilize or test the pH. I just went out with my little trowel, picked a spot that wouldn’t get in the way of anything else, and tucked them into the ground, sticking a chopstick nearby so I wouldn’t forget the exact spot. I felt like I’d thrown a child into the deep end of the pool and was waiting to see if they could swim. We’d find out sometime next year, I thought.

A few weeks later, I watched from the kitchen window as my partner rooted around in the corner of the garden where I’d planted the garlic. He’d lived the past fifteen years in Brooklyn and was excited finally to have a yard. He’d spent the spring and summer planting and harvesting tomatoes, eggplant, and peppers. He’d put in a blueberry bush, learned how to wrap our fig trees. I hadn’t mentioned my plan, so I was surprised when I walked over with my coffee cup that Saturday morning in November and he proudly showed off his three tight rows. Garlic! he announced. He’d bought some seed bulbs from the farmer’s market and, after testing a few different soil patches across the property, determined that this was the best place to plant them. I laughed and pointed to my little chopstick poking out of the ground a few feet away.

I told him I didn’t expect the Pennsylvania garlic to grow. I think I meant it. He ordered some garden straw and covered the soil. From the kitchen window, the patch of hay glowed in the moonlight, as if it were Rumpelstiltskin’s tower- room floor, waiting to be transformed to gold.

The next spring, I watched twenty-one green shoots emerge from the perfect rows my partner had planted. Every morning, I counted them, charted their growth. And every morning, the dirt by my little chopstick remained flat and sandy. It was only May; we had time. As spring pressed on, the lilacs bloomed, the figs unfurled their leaves, and I stopped worrying so much about the Pennsylvania garlic. The roses and peonies shook out their bright heads, the Montauk daisies popped. In early June, I spent an afternoon pruning the lilac trees.

Did you look up on the internet how to do that? my partner asked that night. Often, he will tell me how to grow plants and vegetables. I’ll listen and wonder, does he not remember that I spent ten years in the country before I met him? Instead, I hold my tongue. When he planted the garlic in mid-November, I did not tell him I thought he’d waited too long. When he planted the bulbs so close to one another, I did not suggest he thin them out. When it was time to cut the scapes, I tried to note this neutrally: The scapes curled! Want me to cut them, or would you like to do the honor? He replied that one should not cut the scapes, but snap them off. Sure, I thought, if you want your fingers to stink like garlic for a week; I’ve done both. What matters is that you get the scapes off the plants within a week of them curling. It’s the timing that matters, so that the scapes don’t suck the life out of the bulbs below. Of course, he didn’t seem to follow the rules I knew, and yet his garlic was growing.

I wonder how much I’ve actually said out loud. We’ve been together for years, but we each had whole lives before. He couldn’t know my hands were, for so long, permanently calloused in the summer from weeding, crosshatched with yellow-brown along my thumbs and pointer fingers. Or how my husband and I would set the babies down in the dirt for the first snow shower to seed the garlic patch, using the rocks that ringed the garden as a makeshift playpen. Did he know I drove around for two weeks with my old wedding dress in the back of my car because I did not want to bring it into our house? Could he sense how much I wanted those little garlic cloves to die and, at the same time, prove to me that something could be transplanted and survive?

By the time I heard the news about Mary Anne’s cancer, I hadn’t seen her for years. She went quickly, with only a few short weeks between diagnosis and hospice. I did not go to her funeral, did not send flowers or my regrets, though I had many.

No one in my new life knew her, so I mourned alone. I read her obituary, her Rate My Professors page. I looked at grainy photos of her bright-white bob and thought about the afternoons we spent together so long ago, when she was trying to bury her father and I was trying to learn how to be an artist’s wife. I made myself a grilled cheese with supermarket garlic and ate the whole thing at my kitchen table, surrounded by my children’s art.

I don’t think I ever mentioned Mary Anne to my new partner. Or if I did, I don’t think I mentioned the garlic, or our talks. I don’t know where I would begin. How would I explain that, at the time, sixty seemed so far away; now I’m nearly there and my life looks nothing like I thought it would.

As I kept daily vigil over the little chopstick, watching for signs of growth, I continued to think about Mary Anne and her choices. I’d already put the garlic in the ground; it was too late to cut it up, to serve the cloves to someone else to swallow down. For a while, I imagined that, if the plants survived, I would split and replant them the following year, again the year after that. And after a few seasons, when I had enough to spare, maybe I would wrap two cloves in a paper towel and seal them in a plastic bag and gift them back to their father.

But now, if the garlic makes it, I think I would like to drive up into the Gatineau Hills, find out where Mary Anne is buried. I’ll check the Almanac for the best time to go and, trowel in hand, I’ll tuck the garlic close to her headstone to give the green spears the best shot at escaping the caretaker’s Weedwacker.

Perhaps the garlic will molder and die. Or maybe, nine months later, a tender shoot will emerge from the dirt and begin the process anew.

Melinda Josie is a freelance illustrator whose clients include the New York Times, the Atlantic, TIME magazine, Chronicle Books, and Penguin Random House Canada.