The Distance Between Us

audio slideshow

-

It’s two in the afternoon, and he’s finally waking up. The night before, Nick was alone in the basement surfing the Internet, playing games, and going outside three or four times for a smoke in the backyard.

-

Nick has been getting bad cramps again. Earlier tonight he came out of his bedroom with his knee turned in, barely able to walk. It was hard to look because it appeared broken at the knee. Mom and Dad helped him into bed, straightened his leg against the end of his bed, and gave him medicine to relax his muscles.

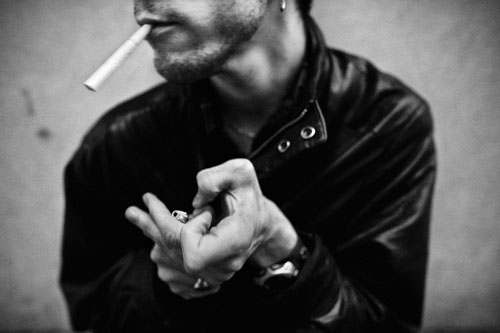

The way I remember it, there was such coldness in the air that it cut right through us on that January morning in New York City. Nick leaned against a fire hydrant and lit up a Marlboro red. It was a normal winter day in 2007, and everyone on the street was bundled up, but Nick was only wearing his leather coat. He looked like such a rock star in that jacket. While we waited for him to finish his cigarette, a passing woman glanced at me, then down at Nick, who looked up slowly and grinned. She fleetingly returned his smile, and he took another drag with the fading smirk still on his lips.

I’d like you to meet my brother. I’ve been drawn to photographing him for as long as I’ve been making pictures. The time I spend with him, looking through my camera has forced me to ask questions about suffering, and faith and why anyone is born with disease. Nick has cerebral palsy. The pictures have been a way for me to deal with the reality of having a twin brother who struggles through life in ways that I do not. Photographing him was not something I set out to do, but over the years, one picture has lead to another and his story has emerged.

On that January morning, we were staying with our sister at her place in Brooklyn. When we filed onto the R train around the corner from her apartment, we were all looking forward to seeing the rodeo at Madison Square Garden later that evening. But as Nick stood in the jostling car, holding onto the overhead bar, I could see his hand begin to turn in, clenching tightly. His leg buckles inward and he swayed as the train jerked and came to a screeching stop. When the man next to him got up, Nick sat, and I could see it beginning to happen.

A cramp was coming.

Click below to watch Christopher Capozziello’s audio slideshow “The Distance Between Us.”

Nick’s countenance changes when a spasm is coming on, even before his body goes rigid. His mouth shuts and his lips pinch together. I can see it in his eyes, the way he looks slowly at me and then slowly away. It is this look that transforms him from my twin, my equal, to a younger dependent brother. But this is just the beginning. Next, he will be unable to talk and his body will contort and lock: his right arm will twist behind him, his right foot will curl beneath him and he will be incapable of walking on his own. It may last minutes, or hours; sometimes his muscles cramp for days.

When we got off the train, he limped toward the stairs. For us, this is normal, a part of our lives that we have always lived with as far back as I can remember. He will put his left arm around my neck, holding my shoulder, and I will slip my arm down across his back and around his waist to help him, but this time he said, just above a murmur, “No, I can do it myself.” So I stood behind him in case he fell backward and watched him struggle up the stairs.

-

Nick smokes. He has been unable to hold down a job because of the muscle spasms, and when he is around other smokers, it’s a way for him to connect with them. But, Nick is diabetic and at tremendous risk of stroke and heart disease. He has tried quitting.

-

When I visit home, I can almost always find Nick in his room on the computer, playing Farmville or listening to music.

-

When I photographed Nick at the Ale House, a woman asked if I was making fun of him. I told her I was his twin brother. She yelled over Nick’s singing, ” ‘Cause if you’re making fun of him, there are a lot of guys here who wouldn’t like that!”

You can’t test for cerebral palsy. It isn’t so much a defined condition as a set of symptoms, the aftershock of an explosion no one hears. For Nick, that explosion came at birth. When he was born, he was not breathing. The doctors immediately began working on him, and then things seemed fine. It wasn’t.

Dr. Gulash, our pediatrician, began noticing that I was developing normally, reaching expected milestones on time—lifting my head, rolling over, sitting up, grabbing onto things— while Nick was doing everything two months after me. He suspected something was wrong, so he began testing. Before our second birthday, he had a diagnosis for our parents: cerebral palsy. But still, my mom and dad weren’t concerned because we seemed relatively similar. It wasn’t until we were three, when Nick was watching television on the living room floor, that Mom noticed something was wrong. He sat with his arm straight up in the air.

“Nicholas, why are you sitting with your arm up?”

“It just went up, Mommy,” he said.

“Can you put it down?”

He reached up while still watching television, and with his left hand, pulled his right arm down. It all went downhill from there.

We grew up with this together, the two of us, but it wasn’t until I was school-aged that I started to see the differences between us. We’d be out throwing a baseball or playing basketball, and just that much physical activity would trigger a cramp. If we were home, I would carry him inside, take off his shoes, and put him in bed. Sometimes if we were only a few houses down, our friends and I would carry him up the street. I would have his arms, and the others would grab his legs.

In high school, Nick’s adolescent growth spurts brought on terrible spastic cramps. All of us would have to hold him down at once—Mom and Dad, our sister, and I—so he wouldn’t hurt himself. His arms and legs would flail wildly, sometimes hitting himself, sometimes hitting us. His back would arch, his head would rise up and then come crashing down onto the wood floor. His jaw would open wide and then clench down tightly, sometimes on his tongue.

These days, Nick likes to go to the Orange Ale House. It’s a nothing little bar in a strip mall not far from the interstate. A few pool tables and dart boards, beer and bar food. Nick goes for the karaoke. He wears this cowboy hat and belts out the songs.

Once, recently, a woman came up to him afterward and took hold of his hand.

“I like a man in a cowboy hat,” she said, “but where are your boots?”

Nick smiled. “They’re at home, but I’ll wear them for you next time.”

And every time since, when we go out, he wears his cowboy hat and boots—but we haven’t seen her again. That’s one of the hardest parts about being Nick’s twin: living my life, knowing that most of my experiences will forever be out of his grasp. Cerebral palsy makes the easy things in life difficult: eating, playing sports, holding a job, learning to drive, having a girlfriend. Nick understands enough about the world around him to know what he is missing.

We were raised Catholic, and so the idea of a loving God has always been a part of our lives, but recently I asked Nick if he ever gets angry. “I sometimes wonder why God put me on this earth the way I am,” he said. “It feels like He doesn’t answer me, but I never get angry at God because if I didn’t have cerebral palsy I would be a different person.” I have a hard time being so accepting. From time to time, someone will ask if I feel guilty that I’m the healthy one. I do. I look at Nick and wonder why he has to be the one who struggles on a moment-to-moment basis. It stirs up this process of grieving that never seems to end, like one long lament.

In November 2009, Nick underwent Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS). For the first time, our family held out hope that things would improve for him. The doctors said that while the surgery might not completely stop his muscles from cramping, it could significantly decrease the effects of the cramps. It could also cause a brain hemorrhage.

DBS is cutting-edge science, but it looks like medieval torture. They shave you bald and rig you to a stereotactic frame, a large metal cage that holds your head steady and drills through your skull to insert electrodes for a “brain pacemaker.” Once they switch the implanted device on, it delivers tiny electrical shocks to your brain, gradually retraining your whole nervous system to relax your muscles.

As they prepped Nick for surgery, screwing his head into the frame, he was obviously afraid. We all were, but we told ourselves it was worth the risk. Then, midway through the surgery, the doctor came to tell my family that they’d had to rush Nick out of the anesthesia; he had quit breathing. “We only got halfway done,” he said. “But Nick’s fine.”

As they prepped Nick for surgery, screwing his head into the frame, he was obviously afraid. We all were, but we told ourselves it was worth the risk. Then, midway through the surgery, Nick quit breathing.

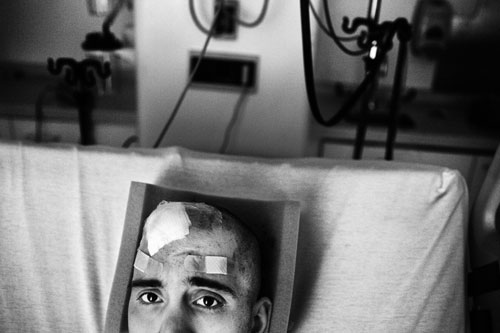

For weeks after, Nick said that he didn’t want to complete the procedure, but in February he decided to go through with it. The second time everything went fine, but it would be several more weeks before they would turn the pacemaker on. Just after the surgery I made a picture of Nick in bed—his head shaved and bandaged in the foreground. What hits me the hardest is the look in his eyes. I don’t see my brother like this often. Even when he’s in the midst of a cramp, I’ve seldom seen him this power less and afraid. As we waited there, we were all wondering what was going to happen, whether all he’d just been through would be worth it.

When I arrived home this Thanksgiving, Nick was in the bathroom shaving. It had been a year since he underwent Deep Brain Stimulation. I knocked on the door and opened it up. Nick turned his head very slowly and looked at me. He smiled, but it was more like a wince. I could tell, without him saying anything, that he had a cramp. But, since the surgery, the effects have been much less severe. In the past, he would have been in bed all day and missed the holiday; this year, I could tell he was hurting, but he was able to enjoy Thanksgiving with us. It’s still not easy—for him or for us—but it was beautiful that this year I could sit across the table from my brother, my twin, and make pictures of him eating dinner, laughing. For my family, this surgery is the closest thing to a miracle we can expect.

-

Following the Deep Brain Stimulation surgery, he was unable to shower until the staples had been removed.

-

During the first surgery Nick stopped breathing, and the doctors had to pull him quickly out of the anesthesia before they were finished. They told him that he didn’t have to go back for the other half of the surgery, but I pulled for him to do it. “Why only fix half the problem,” I questioned. He was afraid of having the metal frame screwed into his head again. They did that while he was awake and he was only given topical Novocain. But, two months later, we were back in the hospital, and it was finally over. Now we wait to see what the surgery will do for him.