Night Moves

Every civilization we know of has devised a system—scientific, religious, numinous, what have you—to make sense of the night sky. The mystery of what’s up there, where it came from, and what it means has long transcended geographic and cultural barriers. It has been inherited and puzzled over for generations. Questioning the universe’s origins and its contents feels innate to our humanity; those questions might be the most human ones we have.

Due to pervasive light pollution—glare from excessive, misaimed, and unshielded night lighting—80 percent of Europe and North America no longer experience real darkness. By extension, these populations possess a compromised understanding of the night sky as vista, a shifting landscape of constellations and planets, as multitudinous and astounding as any Earthly terrain. For anyone living near a major metropolis, a satellite image of the Milky Way is even more abstract and antipodal than a Brontosaurus skeleton posed in a museum: We understand it to be a document of something true, but that understanding remains purely theoretical. In 1994, after a predawn earthquake cut power to most of Los Angeles, the Griffith Observatory received phone calls from spooked residents asking about “the strange sky.” What those callers were seeing were stars.

I grew up in a small town in the Hudson River valley, about an hour north of New York City. Like most children, I regarded the night sky (or what I could see of it) with extraordinary wonder. I understood that nobody could say for sure what was out there. Little kids are often frustrated by the smallness of their lives, in part because the imagination-to-agency ratio of the average toddler is roughly infinity to one. As a child, you can conjure complex, unbound, spooling worlds, but in your own life, you are largely powerless to make significant moves. Looking up, the tininess I felt was validated, confirmed, but it no longer felt like a liability. If the night sky offers us one thing, continuously, it is a deeply liberating sense of ourselves in perspective, and of the many things we can neither comprehend nor control.

“I wish to know an entire heaven and an entire earth,” Thoreau wrote in 1856. He understood heaven and Earth as separate, but still in some essential conversation with each other—as if to receive one without the other was to misunderstand both. But how can we know a heaven if we can barely see it? What happens when mankind divorces itself from a true experience of the cosmos, separating from the vastness above, taming it by erasing it? If you keep distilling the problem—boiling and straining—it becomes wholly spiritual. Thoreau’s wanting feels important, imperative. Humans have lived and evolved under the stars for millennia. It isn’t unreasonable to think that some part of us is designed to orient around them, to learn from them, and that we are right now failing this part of ourselves.

In 2001, the amateur astronomer John Bortle devised a scale to measure relative darkness. His classifications range from “Inner-City Sky” (Class 9), in which the only “pleasing telescopic views are the Moon, the planets, and a few of the brightest star clusters (if you can find them),” to a sky so dark “the Milky Way casts obvious diffuse shadows on the ground” (Class 1). Most North Americans and Europeans live under Class 6 or 7 skies, in which the Milky Way is undetectable and the sky has been smudged by “a vague, grayish white hue.” In that kind of night, a person can wander outside, unfold a lawn chair, open a newspaper, and recite the headlines, if not the stories.

Darkness is a complicated thing to quantify, defined as it is by deficiency. In addition to the Bortle scale, scientists often use photodiode light sensors to measure and compare base levels of darkness by calculating the illuminance of the night sky as perceived by the human eye. Unihedron’s Sky Quality Meter is the most popular instrument for this kind of measurement, in part because of its portability (about the size of a garage-door opener) and also because it connects to an online global database of user-submitted data. According to that database, Cherry Springs State Park—an eighty-two-acre park in a remote swath of rural, north-central Pennsylvania, built by the Civilian Conversation Corps during the Great Depression—presently has the second darkest score listed (23.27, reported in 2007; 23.69, the highest ever recorded, was taken on a ranch in Big Smoky Valley, Nevada, in 2011). On the Bortle scale, Cherry Springs usually registers between 1 and 2. The International Dark-Sky Association (IDA), a nonprofit organization that recognizes, supports, and protects dark-sky preserves around the world, designated it a Gold-tier International Dark Sky Park in 2008, only the second in the United States at the time, following Natural Bridges National Monument in San Juan County, Utah.

Earlier this year, I drove the six hours to Cherry Springs from New York City to meet Chip Harrison, the park’s manager, his wife, Maxine, and a park volunteer named Pam for a 4:30 p.m. dinner of baked fish. Afterward, Chip had promised, we’d go see stars.

“Most children, right now, growing up in the US, will never see the Milky Way,” Chip said while we waited for our entrees.

“Their parents never saw it either,” Maxine added.

“You come to a place like Cherry Springs, you’re gonna see four or five thousand stars, maybe more,” he continued. “I’ve seen people who are fairly serious amateur astronomers, and they can’t find their way around this night sky—there are too many stars.”

After supper, we drove to the park, arriving around sunset and unloading several bags of equipment from the trunk before setting out, together, into the blackness. White light isn’t permitted on the astronomy grounds, but red-filtered light, which won’t cause the rods of the eye to become overexposed and less efficient, is allowed if not quite encouraged.

“If you hear crunching, you’re on the right path,” Maxine announced over her shoulder. I only presumed she said it over her shoulder. The dark around us was compact, bottomless, sonorous. I was echolocating poorly. I blinked city eyes. We crunched along a gravel path toward the astronomy field, where Chip was assembling an Orion SkyQuest telescope. The SkyQuest is a large-aperture, reflecting scope—a design actualized by Isaac Newton in 1668 and adapted, three hundred years later, by an amateur astronomer and Vedanta monk named John Dobson. It’s stout but sizable, about eight inches in diameter, and is ideal for locating deep-sky objects like dim star clusters, nebulae, and galaxies. Chip was piecing it together on top of a small concrete slab.

At the edge of the field, a former airstrip, killdeer cheeped eagerly, constantly; a woodcock sounded a burp-like call. It was four days after the new moon, and the sky was so black that even the tiny slice of visible moon—a dainty, waxing crescent—felt like a bare bulb screwed into the ceiling of an interrogation chamber.

On a clear night, from the proper vantage, watching constellations emerge over Cherry Springs is like watching a freshly exposed photograph sink into a bath of developer, slowly becoming known to the eye: a single crumb of light, then another, until the entire tableau is realized. Pam pointed the telescope toward Jupiter, which had risen over the east end of the field. The four Gallilean moons—Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto—were clearly visible through the lens. Galileo discovered these moons in 1610, in the skies above Padua. They were the first celestial bodies proven to be orbiting something other than Earth, thus thwarting Ptolemy’s geocentric world system. With my face still pressed into the telescope, I gasped.

Pam laughed. “Usually when people look through the telescope, I point out the big ‘wow’ items, like the planets, Saturn and Jupiter, some of the clusters,” she said. “Everybody looks at them and goes, ‘Oh, my God.’ They go, ‘Is that real?’”

Cherry Springs is singular in that it is located less than 300 miles inland from the Eastern Seaboard, in a region—the East Coast—that contains 36 percent of the country’s total population and is lit up like one of those backstage makeup mirrors every night of the year. When pinpointed on a satellite image, Cherry Springs is in the middle of an uncharacteristically dark patch—insulated, on all sides, by protected land (262,000 acres of Susquehannock State Forest, an impenetrable thicket of eastern hemlock and white pine), and perched atop the Allegheny Plateau, 2,300 feet above sea level. Most of the small towns surrounding the park are situated in valleys where outdoor light is already sparse (the 2014 census estimate puts Potter County at just over 17,000 residents). This unusual combination of factors explains, to a certain degree, how Cherry Springs became one of the darkest places in America.

Which isn’t to say the sanctity of the sky here is not being encroached upon. In the last decade, a handful of energy companies (the Chesapeake Energy Company, the Seneca Resources Corp., Pennsylvania General Energy, and others) have begun extracting natural gas from the Marcellus and Utica Shales underneath Pennsylvania via hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, a much-reviled practice that involves the release of gas or petroleum via a high-pressure injection of fluid through a narrow shaft bored into the ground. In Potter County—god’s country, the signs promise—there are presently forty active fracking sites. The work cycle in a gas field is nonstop; energy companies not only rig up colossal, stadium-style spotlights, they also burn off excess gas in open pits or through steel pipes, in a process known as flaring.

From afar, a flare resembles a giant blowtorch; clusters of flares are clearly visible on satellite images from space. One of the wells closest to the Cherry Springs astronomy field—Ken Ton 902 3H, operated by Swepi Lp, a Houston-based subsidiary of Shell—has accumulated twelve violations since it opened in 2009, including “discharge of pollultional material to waters of Commonwealth.”

The Utica Shale, which underlies much of the northeastern United States and parts of Canada, is already a source of so-called “tight gas”—gas contained in rocks so impermeable it can only be accessed via fracking—in Quebec, but energy companies in Pennsylvania have recently begun experimenting with mining it (a 2012 report by the US Geological Survey suggests the Utica Shale might hold up to 38.2 trillion cubic feet of “technically recoverable” gas; in parts of Pennsylvania, it’s extraordinarily deep, reaching to almost two miles below sea level, and several thousand feet deeper than the Marcellus Shale).

Chip—who is exceedingly kind and mild- mannered, possessing the sort of preternatural calm seemingly required of park rangers—has worked out an informal agreement with representatives from nearby wells, in which workers abstain from flaring at night during Star Parties, when amateur astronomers gather in Cherry Springs to observe and record astral phenomena, or when the park is hosting astronomy-related public programs. But it’s chiefly a gentleman’s agreement, reliant on neighborly goodwill. At present, there are no light-pollution restrictions placed on energy companies by the state of Pennsylvania.

Chip puttered around the perimeter of the field. He mentioined something about elk. “Most recently, JKLM Energy, which is drilling locally here—they elected last summer not to flare,” Chip said. Pam adjusted the telescope.

“The flare from a Utica well is serious,” Maxine said, in a voice that had taken on a heavier timbre.

“A flare can essentially put out as much light as a town of four thousand people,” Chip said. “It is very bright. [JKLM] elected to do daytime flaring only, so that they would not impact the dark skies here. But at the same time, I believe it’s a two-way street. During the dark of the moon, and if it’s going to be raining, I find it amazing that I’m e-mailing back and forth saying the forecast is this, there’s no reason you can’t flare tonight.”

Chip hadn’t anticipated becoming a dark-sky steward. Maxine tells me he used to go to bed at 9 p.m. every night. “It’s been a very neat journey, the development of this,” he said. “In this day and age, it’s not often that someone like me, a resource manager, gets to be involved in a brand new resource. You get to thinking you know everything.”

Gary Honis, an electrical engineer and astrophotographer based in Sugarloaf, Pennsylvania, has been visiting Cherry Springs for twenty-five years, since long before it was recognized internationally for its dark skies. Feeling disheartened by the bright skies in their area, his local astronomy group had “pulled out an old Air Force map, a satellite map, that showed a dark area in Potter County. We compared that to a Pennsylvania road map, and it was Cherry Springs State Park. That’s how we found it, by looking at light-pollution maps. My first view was through a friend’s six-inch Dobsonian telescope, and it was of M51, the twin galaxies in Ursa Major,” Honis said when we spoke on the telephone. “It looked photographic. We never saw that back home.”

Chip eventually came upon Honis, tented by foil, peering up at the heavens. The park had been closed for hours, but Honis convinced Chip to let him stick around and take some pictures. Their meeting was serendipitous. With Chip’s advocacy, the park’s hours eventually changed to allow for visiting stargazers, who, with the proper permit, can now camp overnight on the astronomy field.

Since then, Honis has been outspoken about the effect fracking is having on the skies above Cherry Springs. He’s posted videos to YouTube—often accompanied by ominous music he performs himself on his Moog Theremini—linking fracking to declining sky-quality readings. The videos are convincing, showing, via time-lapse photography, how gas flares and unshielded drill-site lights are compromising the park for astronomers (his entire video page is worth perusing; in one clip, a mangy brown bear, “Mohawk Moe,” wanders onto the astronomy field and ambles toward Honis’s friend Tony, who is eating pepperoni). “We started doing sky quality meter readings of the night sky brightness in 2006, and since then, the skies over Cherry Springs have been getting much brighter,” Honis said. “Ten years ago, the only sky glow we had was in the Coudersport area, in the northwest direction, and it was very minor. If you’re truly dark-adapted, now you can see sky glow [close to the horizon] across the north, the east, the south, and even the west. It’s all around now, on a moonless night. We didn’t have that years ago. When the fracking started, sky quality readings went very bad.”

The nocturnal world, of course, also generates its own light, and those deviations can affect dark-sky conditions. The National Park Service cites moonlight, starlight from individual stars and planets, the Milky Way (also called galactic light, or integrated starlight), zodiacal light (sunlight reflected off dust particles in the solar system), airglow (a faint aurora caused by radiation striking air molecules in the upper atmosphere), wildfire, lightning strikes, and meteors as organic sources of evening light. Atmospheric moisture or dust particles can refract or reflect that light, amplifying glow (deserts, for example, are low in moisture but high in dust; forests are the inverse). Air pollution makes it all worse.

In Cherry Springs, Maxine—a former game warden, one of just a few women to hold that position in Pennsylvania—had fixed her gaze toward the sky. We were quiet. The night wasn’t perfectly cloudless—it had rained earlier; ambient moisture lingered—but the viewing conditions were favorable. Everyone agreed we’d gotten lucky. Maxine was wearing a pair of dangly moon-and-stars earrings, which glinted in the starlight. “This is where the word awesome comes from,” she whispered.

In the seventeenth century, under the reign of the self-described Sun King, Louis XIV, tallow candles fashioned from rendered beef or mutton fat were placed in iron-framed glass boxes and strung above the streets of Paris. Lamplighters wandered the districts of the city at dusk, unlocking the boxes and igniting the wicks (mischievous vagrants and the over-served often yanked down and smashed the boxes, a wilding tradition that endures today in cities where inconveniently placed streetlights are often shot dark, presumably to facilitate illegal transactions).

Other places followed Paris’s model, and candles eventually gave way to oil and then gas lamps. By 1890, more than 175,000 electric streetlights had been installed in the US; there are now somewhere around 26 million, which collectively cost American taxpayers about $6 billion in annual energy costs. The idea at its inception—an idea that has endured—was that street lighting would help officials of the state more effectively survey and control city streets after dark. Whether streetlights actually make anyone safer remains a contentious topic. Most studies fail to indicate a clear or inarguable correlation between street lighting and decreases in traffic accidents or crime, although it feels willfully obtuse to suggest that taking the dark way home is always just as safe.

Street lighting is undeniably pervasive, but it isn’t the only culprit of our perpetually bright skies. Light pollution is aggravated by any kind of irresponsibly aimed outdoor lighting: stadium floodlights, the beams dissecting superstore parking lots, illuminated billboards, futuristic Exxon stations beckoning tired drivers toward off-ramps with neat rows of pumps, roofs pocked with glowing bulbs—any umbrella of safe, welcoming, antiseptic light. Proper shielding and direction can mitigate the glare of these often blinding emanations, and the IDA publishes guidelines for easily modifying outdoor lighting to be more dark-sky friendly. But in most places, following the IDA’s suggestions is optional. The right to light isn’t easily denied.

In recent years, Chicago, Seattle, Boston, Philadelphia, Detroit, and Los Angeles have been swapping out the high-pressure sodium bulbs in their streetlights—which produced puddles of gassy, orange-hued light, that grittily romantic, archetypal streetlight glow—for comparably cost-effective LED bulbs. Sodium bulbs are usually around 2,200 kelvin, a temperature that registers to the eye as warm. LED bulbs burn closer to 4,000 kelvin and emit an intrusive, bluish glare. If you live in a major American city, it is virtually impossible to spend any time at all in the dark.

The new LED streetlights are almost universally described as unpleasant. New York City is presently in the midst of its own retrofit, a colossal overhaul scheduled to be completed by the end of 2017. The bulbs last longer and will ultimately reduce energy use by up to 75 percent, according to the US Department

of Energy. But after the new bulbs were installed in Windsor Terrace, a residential neighborhood in Brooklyn, citizens reacted with disbelief. In an opinion piece for the New York Times Sunday Review, the novelist and Windsor Terrace local Lionel Shriver wrote: “Although going half-blind at 58, I can read by the beam that the new lamp blasts into our front room without tapping our own Con Ed service. Once the LEDs went in, our next-door neighbor began walking her dog at night in sunglasses…These lights are ugly. They’re invasive. They’re depressing. New York deserves better.” On the local news, a woman from nearby Kensington announced, “My seventy-four-year-old mother, her glasses go dark when she goes outside, because her glasses think it’s daylight outside.” The woman added that the lights were raising her own blood pressure and giving her anxiety.

Susan Harder, the New York State representative of the IDA and a board member of the Montauk Observatory in East Hampton, has been rallying aggressively against the installation of LED streetlights in New York. “We still think that God lives in the heavens, in part because the sky was so dynamic to ancient cultures,” she explained when I asked her to expand the problem beyond the bulbs themselves. “How could you ignore a changing, moving night sky? It struck them with awe. They attributed all sorts of things to the night sky. We’re going to lose that if towns and cities keep installing these LED streetlights.”

Harder previously had a career as an art dealer (she was the associate director of the LIGHT gallery, once one of only two galleries in New York City dedicated entirely to photography), but now works full time as a dark-sky activist; in 2010, she was named the Long Island Sierra Club’s Environmentalist of the Year. Harder has the kind of fast-talking, no-nonsense comportment that recalls Rosalind Russell in His Girl Friday, and is, by all accounts, a formidable opponent. In 2006, a New York Times reporter described her as “a virtual one-woman dark-sky mover and shaker,” and characterized her particular approach to advocacy as a “combination of sweet talk, cajoling and bullying.”

“The New York City Department of Transportation [DOT] absolutely, positively refuses to listen to any common sense about LED streetlights,” she told me. “We shouldn’t be using any LEDs outside until they improve the technology and bring down the blue light, which they can do. But DOT won’t listen to us, so we’re trying to get legislation passed in the city council.”

The bill Harder was referring to, sponsored by city council member Donovan Richards Jr., is clear in its expectations: “This bill would require that any lamp installed as part of the lighting of streets, highways, parks, or any other public place have a correlated color temperature no higher than 3,000 kelvin. All new and replacement outdoor lamps would be required to meet this standard.” It was introduced to the council last summer, and is still under consideration.

When I mention that there’s not a lot of reliable data proving streetlights actually prevent highway accidents, she sounds immediately exasperated. “It sounds counterintuitive, but we don’t need them anymore. The majority of the roadway lighting we have in our country is unnecessary,” she said. “Cars have headlights. The whole Long Island Expressway is lit up, and it doesn’t need to be.”

Of course, electric lighting, employed judiciously at night, can be terrifically beautiful. Large-scale light artists like James Turrell, who deliberately seek out areas unmarred by light pollution, manipulate and re-contextualize light in astonishing ways. And sometimes light at night is unquestionably necessary, like the lights that land airplanes, or the ones that warn passing ships away from outcroppings of rock.

But a wanton insistence upon light can also be very dumb. Consider the colossal beam shooting into space from the top of the Luxor Resort & Casino in Las Vegas. The beam is described, in press materials, as being visible from 275 miles away by an aircraft at cruising altitude, and as “the brightest single visible light on Earth.” There is something nearly petulant about it: light for light’s sake, a perfectly erect middle finger to the natural world.

The single biggest challenge facing dark-sky advocates is working out a way to change our fundamental understanding of darkness as a nefarious force, a thing that needs to be avoided or controlled if not vanquished entirely. This is an obvious vestige of an evolutionary process: For millions of years, our most aggressive natural predators hunted us nocturnally. Early man didn’t stand a chance against a pride of lions slinking across the African plains in the dark; it was clearly to his advantage to stay curled up in a cave. There were other dangers at night, too: walking directly into a tree branch at an unkind angle and inadvertently kebab-ing an eyeball, stepping on a coiled snake, wandering through the wrong spider web, and so on.

But there’s a significant gulf between fearing death by lion and fearing darkness itself. What might seem like a logical and instinctive aversion—our vision is impaired at night—has been socially reinforced via so many disparate avenues that it’s exhausting to even try to tally them up. From a very young age, we are taught that nighttime is when dubious things transpire: nothing but trouble out there in the blackness. At best, night is considered a middling expanse (“No occupation but sleepe, feed, and fart,” is how the Jacobean poet Thomas Middleton put it). At worst, it is terrifying.

In his book At Day’s Close: Night in Times Past, A. Roger Ekirch historicizes this anxiety, detailing the ways in which nearly every known civilization figured darkness as a source of evil: “Everywhere one looks in the ancient world, demons filled the night air,” he writes. Even in our earliest folklore, night is put forth as a proxy for wickedness, worthy of trepidation. According to the Illiad, Nyx, the Greek goddess of night, was a foreboding enough force she made even Zeus quiver and recede; Nyx eventually birthed a delightful crew, including Moros (Doom), Thanatos (Death), Momus (Blame), Oizys (Pain), Nemesis (Retribution), Apate (Deceit), and Eris (Strife).

Christianity positioned God as a source of eternal and unblinking light, a corrective to spiritual darkness and chaos. The narrator of St. John of the Cross’s “Dark Night of the Soul”—still a foundational text for Catholic mystics, recounting, as it does, an intimate union with the Divinity—traverses the night to achieve a final, ecstatic communion with God in which “All ceased and I abandoned myself.”

Torches, candles, oil lamps, gas lamps, the light bulb—facilitators of productivity and examples of the extraordinary ingenuity of man, sure, but also sacred talismans to ward off ever-encroaching night and the malevolence it supposedly enables. In “Nightfall,” from 1941, Isaac Asimov describes a fictional planet called Lagash, which is continually illuminated by six suns. When darkness finally comes to Lagash via a series of eclipses, its population goes completely insane. A Cultist finds a prophecy redeemed: “And in this blackness there appeared the Stars, in countless numbers, and to the strains of music of such beauty that the very leaves of the trees cried out in wonder. And in that moment the souls of men departed from them, and their abandoned bodies became even as beasts.”

Most historical reasons to fear darkness are now moot, easily recognizable as hysterical. Our unease at night is more transcendental than pragmatic. It’s true that a lot of American crime transpires at night, although not as much as one might presume: Per the Bureau of Justice Statistics, 67.5 percent of violent crimes actually occur during the daytime, between 6 a.m. and 6 p.m.

Still, a kind of basic, axiomatic discomfort with darkness persists. Anyone who has stayed up until dawn fretting about the future, suffering through the gloaming, hungrily watching the sunrise, cherishing the relief it entails (“People are buying newspapers!”), understands the weirdness of night in her bones. Awake in the dark, we are scared, vulnerable, and existentially afloat. Reconfiguring deeply engrained cultural ideas about darkness is a complicated task. It’s not just darkness we fear, it’s the vastness and loneliness of the universe, spreading out from here to God-knows-where. The relative size and emptiness of the universe is a lot to hold in mind: “The eternal silence of these infinite spaces terrifies me,” Pascal admits in his Pensées.

I wrote to Ekirch to see how he understood the stakes. His research on “segmented sleep”—the revelation that Western civilizations once practiced a biphasic sleep pattern, wherein two periods of nighttime sleep were punctuated by a brief, intervening period of wakefulness in which they prayed, wrote, had sex, or committed petty crimes—is still considered revelatory, seminal. He is a person who knows from night, understands the ways in which a true experience of darkness is fundamental to our humanity and our interpersonal relations. “At the least, we stand to forfeit age-old opportunities for human intimacy of the sort that darkness alone enhances—not just by affording privacy but by drawing couples closer together physically and emotionally,” he replied in an e-mail. Then he quoted an anonymous early Italian essayist, who positioned darkness as its own lubricant for human communion: “Darkness made it easy to tell all.”

Ekirch also evoked the idea that, centuries ago, the night sky itself was powerful enough—irrefutable enough—to trump even the most pervasive cultural institutions. That’s nearly impossible to conceive of now, when the night sky barely registers to most Americans. “Prior to the Industrial Revolution, night as a source of inspiration knew no bounds, all the more as vestiges of church and state, to name but two powerful institutions, receded in the darkness,” he wrote. “On a moonlit evening in Naples, Goethe felt ‘overwhelmed’ by ‘a feeling of infinite space.’ Exclaimed an English laborer in the eighteenth century as he treaded home from an alehouse: ‘Would I had but as many fat bullocks as there are stars.’ To which, replied his companion, ‘With all my heart, if I had but a meadow as large as the sky.’ Today, few modern critics of light pollution, I suspect, could put the case more passionately.”

When I asked James Karl Fischer, an architect and the executive director for the Zoological Lighting Institute—a nonprofit lighting design practice that combines Fischer’s interests and expertise in physics, conservation, and art—how he thought dark-sky advocates could ever begin to overcome humanity’s frenetic insistence upon light, he acknowledged the enormity of the mission, all the ways in which ideas about light, reinforced by folklore, have permeated the collective unconscious. We found shapes in the cosmos, and told tales to make sense of them. Now, those fictions have lost relevance, or have been replaced.

“I think when we start hearing that people want their light, or that they have anxiety about changing it—it’s really a question of language and stories, of how people build up their understanding of the world, their desires and wishes,” he said. “There’s a wonderful figure in Japanese culture, this character called Oiwa. She’s from a ghost story, ‘Yotsuya Kaidan.’ Without being too obscure, the remarkable thing about the story is that Oiwa, the ghost, always comes out of the light. It’s very different from the way current Western movies would portray it.”

He paused, then added: “[In the West], light is always this positive thing. I see this in architecture and lighting quite often. People hang their self-worth on this idea that light is a positive force in the universe without really understanding what light is. I think that’s where the physical model gets to be so important. The physical fact is that light only breaks things down. It’s about destroying chemical bonds. It’s not about creating them.” Light is often as damaging as it is nourishing.

Besides being costly and inefficient, too much artificial light at night is also supremely unhealthy for humans. In 2001, two epidemiologic studies published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute found that exposure to visible light at night was a potential risk factor for breast cancer. Other studies link the reduced generation of melatonin, a hormone stimulated by darkness and inhibited by light, to mood disorders; one, from The Ohio State University, found that chronic exposure to a relatively low level of artificial light at night increased signs of depression in hamsters. Comparable studies have established links between melatonin deficiencies and diabetes, even obesity.

Artificial light is equally threatening to flora and fauna, and can destabilize various ecosystems. It’s been particularly hazardous for sea turtle hatchlings, which, after emerging from their nests, instinctively begin waddling toward the brightest horizon. Historically, that’s always been the ocean, lit up by moon or starlight reflecting off the surface of the water. Now, in nesting grounds in Florida, rare loggerhead, leatherback, and green turtle hatchlings are becoming confused by inland light and crawling away from the water, where they become dehydrated, are hunted by predators, run over by cars, or drown in swimming pools. Meanwhile, seabirds that feed on bioluminescent plankton are being fatally drawn to offshore drilling platforms and the lamps strung up by fishermen to lure squid to the surface, while migratory birds, which instinctively orient around the moon and stars, are becoming confused when moving through major cities at night, colliding into buildings or flying off course. The Chicago Audubon Society presently oversees the Chicago Bird Collision Monitors, a team that protects and recovers migratory birds that have been injured or killed in downtown Chicago. It also advocates for “bird-safe lighting and building design” to reduce collision hazards, and has successfully pushed its Lights Out! program, which asks buildings taller than forty stories to switch off decorative lighting on the upper floors after 11 p.m. and to leave nighttime lights off entirely from 4 a.m. until daylight during both the spring and fall migration seasons.

Light pollution is generally considered a minor predicament even by otherwise ardent conservationists—particularly when compared with more broadly worrisome issues such as climate change. But Fischer believes it’s a deeply urgent concern. He acknowledged that bird corpses (the Chicago Bird Collision Monitoring Team helps feed an extensive avian morgue, drawers upon drawers of stiff little bird bodies, held by the Field Museum) and squished newborn turtles elicit more sympathetic reactions. But mass insect deaths, he said, are just as significant—if not more so.

Entomologists haven’t quite worked out why so many insects practice transverse navigation—engaging in a never-ending series of wild, kamikaze dives toward your porch light, or, in the absence of artificial light, flying at a constant angle relative to a light source like the moon. In the 1970s, Dr. Philip Callahan, an entomologist working for the US Department of Agriculture, floated a theory that the infrared light spectrum emitted by a candle flame is perhaps a strange simulacrum of the light given off by female moths’ pheromones (he’d previously discovered that moth pheromones are luminescent). If Callahan is right, male moths are attracted to candles because they believe a flame is actually a female sending out a sex signal. Whatever the precise cause, artificial night lighting disrupts insects’ normal flight patterns (thereby dramatically altering their migrations), and attracts many that wouldn’t otherwise emerge from their habitats. Once they’ve been hypnotized—a full psychic capture by the light—they’re either zapped on contact, or preyed upon by enterprising predators while they careen about blindly. Occasionally, an insect will exhaust itself and simply drop out of the air.

“It’s a disaster,” Fischer said. “It seems like a very simple thing, but a streetlight—on the coast, in particular—has a cascading effect. And I have yet to hear how it has been beneficial. A bug zapper, we used to joke, was good old country entertainment. But it highlights an incredible problem: If you think of insects as the food for many of the animal classes, for birds and fish, if the insects are removed because of the artificial light, there’s less food for whoever’s there, and the habitat is degraded.”

When I asked what species he thought was presently the most threatened by light pollution, he neither paused nor equivocated. “Humans,” he said.

“Stability is biodiversity,” he went on. “How do you maintain life on the planet? It’s not about fuel. It’s not about a way of life. It’s not about making sure we’re economically feasible. All of those things might be important, but the fact of the matter is, if you’re interested in human life, wildlife is the most important—you really can’t lose that. You can lose fossil fuels. But you can’t lose wildlife. If you lose wildlife, nothing matters, everything goes. Fossil fuels? We’ll say, ‘Okay, we have to change the way we do things.’ Wildlife, though, is the most critical thing. It has to be saved.”

A few weeks before I visited Cherry Springs, I went with a couple of buddies to a sensory deprivation chamber in Brooklyn. Formerly a hallmark of psychological experiments (and, on occasion, deployed as an interrogation technique), sensory deprivation was now being reconfigured as a kind of bourgeois meditation aid: For $99, you could float for an hour in a foot or so of heavily salted mineral water (roughly 1,000 pounds of Epsom salt per tub), calibrated precisely to your body temperature, inside a sealed, soundproof, lightproof, womb-like chamber. The idea was to disappear a little. The stresses and expectations of an accelerated modern life seemed to demand an antidote of, well, nothingness.

I was not a natural inhabitant of the tank. I spent the first fifteen minutes karate-kicking the door open and then pulling it closed again—mostly to make sure it would, in fact, still open and close. I pressed the button that turns the lights on and off approximately fifty times. I decided to stretch one hand out—ostensibly to see if I could still see it in the dark; I could not—and accidentally dribbled warm, salty water into my open eyes, which felt sort of like squeezing a whole lemon deep into the bloodied crevices of a festering wound.

Eventually, once I had tired myself out, I was able to consider the experience of pure darkness, unbroken even by starlight. I understood how people found it curative: There’s a dissembling that occurs, a loosening of certain grips. But darkness, without the galactic punctuations of the night sky—without stars and planets and moons—feels more finite than infinite. It feels claustrophobic.

On my third night in Pennsylvania, I went back to the park by myself, after midnight. I stumbled onto the astronomy field, wearing a pair of pajamas underneath my coat. My rental was the only car in the lot. It had been raining earlier that afternoon, and thick, heavy clouds now hung low in the atmosphere, obscuring the moon and almost all of the stars. It was as dark a place as I’d ever been. There, shivering, I again felt something akin to genuine panic. When the brain is deprived of visual information—when all external stimuli are washed out—we are alone in new ways. I wondered, then, if the dark acted as a kind of Rorschach test: if our perception of it wasn’t also a manifestation of our biggest, most profound fears. Whatever you conjure there, in the blackness, speaks to your innermost terrors: a man with a gun, a bear, a goblin, a ghost. Your own inveterate isolation.

When I got back to New York, I visited with Matt Stanley, a beloved colleague at the university where I teach. Stanley holds degrees in astronomy, religion, physics, and the history of science, and has a particular interest in how science has changed from a theistic practice to a naturalistic one. He leads a seminar called “Achilles’ Shield: Mapping the Ancient Cosmos,” and another called “Understanding the Universe.”

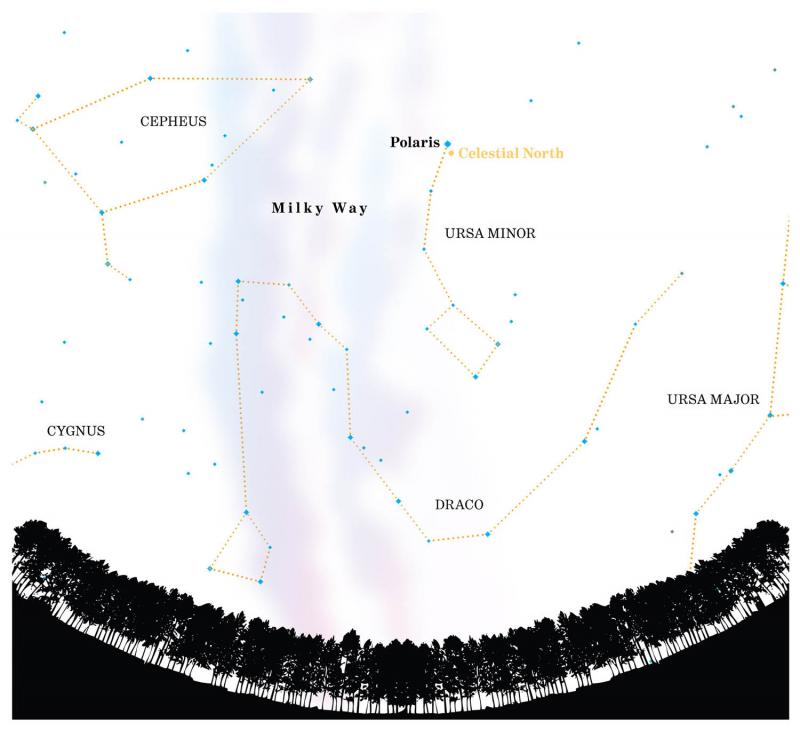

“I’ve found that probably 95 percent of my students come from either an urban or suburban environment, which means they can only see a dozen stars at night, and no planets,” Stanley said. “When you say the Milky Way to them, they imagine a spiral galaxy, which is fine, but that’s not what the Milky Way looks like—it’s a big, whitish smear across the sky. I have to do a lot of work to orient them to what human beings actually saw when they looked at the sky. They don’t know that stars rise and set. Their minds explode.”

An alarmist might wonder if light pollution is effectively ending astronomy—if the skies will eventually become so impossibly illuminated that we’ll no longer be able to identify new celestial objects, given that we can barely see the ones we already know are there. Stanley tells me there’s always been an active debate raging about whether science as we know it could, in fact, be over one day. “This is a trope, going back to Newton—that science is always almost finished,” he laughed. “The historian of science Thomas Kuhn said we have to think that about science, because we need assurance that the science we are doing is correct—that we’re just filling in the gaps. But actually, every now and then, we discover there’s a whole new puzzle.” He continued: “The best astronomy nowadays is being done from space. When I did my astronomy degree, I never looked through a telescope. Now, you can imagine a world—almost a dystopia—where no human being has ever seen a celestial body with the naked eye, but we have fantastically sophisticated astronomy, because we do it all above the atmosphere. It’s efficient, but it breaks with those initial questions: Why does the sky behave like that?”

In many ways, the whole of science was derived from early man’s fascination with the stars. The sky told us what kinds of things to ask. “Science, as we understand it, comes from this very old tradition of trying to understand what we saw in the night sky,” Stanley said.

That inescapable curiosity was the lone catalyst for centuries of intellectual and spiritual growth. Babylonian astronomy gave us time, later mathematics; astronomy is, in one way or another, central to every foundational philosophy we know. Our instinctive preoccupation with the content of the sky seems tangled up, somehow, with all those other inborn human desires: to know and be known. To feel cowed, sublimated. To wonder and to worship.

An optimist might presume that, in its absence, we’ll find new reasons to ask questions of the natural world and of ourselves, and to continually enlarge and revise our understanding of the universe. That we will not, instead, drift further toward a detached, solipsistic worldview that wants for little beyond itself. Still, it’s hard not to do the mental arithmetic—to worry that our disinterest in preserving darkness and our present detachment from it might suggest something troubling about the insularity of the modern condition. What other romantic fascinations will we lock ourselves out of, and at what cost?

“The experience of looking up at the sky—that’s what Kant uses to explain the sublime,” Stanley said. “In 1788, he said, ‘There are two things that fill my heart with wonder. One is the moral sense within me, and the other is the order in the heavens above me.’ That’s an extraordinary feeling, and ineffable. You can’t describe it, but once you’ve experienced it, you never forget it.”

It almost sounded, to me, like Stanley was talking about love. The experience of oneself in relation to an other—the miracle of it, the magnificence.