The Forgotten Village

On an early summer morning at the southern tip of the San Joaquin Valley, the horizon is already smudged with a brown haze, promising yet another day when being outdoors can do more harm than good. Miles from any paved road, Timoteo Bello ambles beneath a bright-green canopy of grape vines, pushing aside a hanging cluster of Thompson seedless that have shriveled to raisins. “Caliente,” he says, indicating the weather. It’s been hot for days; last week, several companies dismissed workers early on account of the heat. But Bello is mostly saying this for my benefit, since he finds summertime in the San Joaquin Valley “pleasant.” If anything, he gets annoyed whenever he isn’t able to work a complete shift, no matter the temperature.

All is quiet but for the buzzing of dragonflies and the faint sounds of a Spanish tune coming from a parked truck. Bello arrives at the beginning of a row, packing grapes into bags and stuffing those bags into a cardboard box, which, when full, weighs twenty-one pounds. He uses a scale to double-check his work, but after nearly three decades harvesting grapes across Southern California, he’s usually on the mark. He peers into the shade of the vines, where his daughter and son-in-law clip off bunches and lay them into trays. There are about three-dozen workers in Bello’s crew. Today, like most days, they will harvest about fifteen tons of fruit.

Bello grew up in central Mexico, which he left in 1984 to work in grapes. Since then, except for a few basic improvements, life in the fields has remained largely unchanged. “We used to kneel in the sun when we packed,” he says, though now a canvas canopy hangs above him, providing shade over a table that allows him to work upright. At the same time that the canopies were introduced, workers were given wheelbarrows, to relieve the burden of having to haul trays of grapes on their shoulders. Such improvements—shade, a wheelbarrow—seem basic, even primitive, and yet they were introduced less than a decade ago.

At midmorning, the crew takes a break beneath the vines. Bello sits on his cooler, munching on a bean-and-beef taco and sipping a Coke. The fifty-four-year-old is built thick and wears a straw hat to shade his large, oval face. A few of his coworkers, their shirts streaked with dirt, stop by from other rows, curious about my presence. “We met in the university,” he tells them, deadpan, eliciting confusion and then deep laughs.

The topic turns to the drought. It hasn’t rained since—well, since anyone can remember, really. And though this doesn’t seem to be a group that worries much, a few people register concern. (“Worst year ever,” the foreman, who has spent more than four decades in the industry, tells me.) The grapes haven’t looked good, and the harvest out here, south of Bakersfield, will end several weeks early on account of the heat. They’ve all heard the horror stories: the farmer who, without water, plowed up his grove of orange trees; the wells that have run dry. Estimates vary, but perhaps 500,000 acres—an area nearly the size of Los Angeles and San Diego combined—will be left fallow this year.

Everyone in Bello’s crew is, in his or her own way, just getting by. But with steady work and a foreman who treats them with respect, they consider themselves fortunate. Over the years, they’ve grown into what feels like a large family. Still, what the future holds is anybody’s guess. Maybe the state will dry up entirely, or maybe the fields will turn back to desert.

Bello shrugs, as if to suggest that everything will work itself out. Not that it will be easy; his experience as a migrant farmworker has taught him that much. Since immigrating to the US, he has toiled and suffered—six years ago, he was at risk of losing his home; before that, he nearly lost his life. He earns just above California’s minimum wage and has little savings. His only plan for the future is to work until his body gives out. And yet here he sits, eating tacos with friends and watching lizards dart along the dusty ground, and it’s reasonable to feel lucky. Farmworkers survived much before, droughts included. Surely they can survive this.

“To the red country and part of the gray country of Oklahoma, the last rains came gently, and they did not cut the scarred earth.” So begins The Grapes of Wrath, John Steinbeck’s epic tale of migration, hope, disappointment, and resilience. Published in 1939, it is a masterpiece of painstaking observation, a book that, while rooted in a particular time and place, continues to gain relevance as the years pass. Ecological destruction, deep inequality, dispossession, an uncertain future: The book explores the experience of living in a world that falls apart, and how, even as seams break, some bonds endure. “The Grapes of Wrath,” writes Steinbeck scholar Susan Shillinglaw, “is a novel that won’t be contained by its setting.”

The book tells the story of the Joad family, which flees the Dust Bowl to arrive in the very same fields in which Bello has spent much of his own working life. Like Bello, the Joads left home optimistic about the future, fueled in part by the promise on a handbill—good wages all season—which Pa Joad brings with him. California promises pleasant weather, productive land, and the chance to leave behind the desiccated past and begin anew. Even the farmwork being advertised seems to offer the occasional sublime pleasure—one could pause now and then in the shade of orange groves to take a bite of sweet fruit; and the grapes themselves are supposedly plenty. Instead, the Joads join migrants who end up moving from one ditch-bank settlement to the next, chased by vigilantes and exploited by ruthless growers.

Steinbeck’s novel was hefty—he called it his “four pound book”—but was far more engrossing than intimidating: In less than a year, nearly half a million copies were sold. The book received American literature’s highest honors, winning both the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award. It was also wildly controversial. Officials of Kern County banned the book. At least one grower burned it. The county chamber of commerce created a film challenging Steinbeck’s portrayal of the exploitation faced by Dust Bowl migrants, entitled Plums of Plenty. Critics accused Steinbeck of being a Communist, of inventing his facts, of painting a picture that bore little resemblance to the reality of migrant farmworkers in California.

But Steinbeck knew his subject. In 1936, he had loaded up an old bakery truck—which he had converted into a camper—for lengthy reporting trips across the state, visiting fields and labor camps. “The communities in which these camps exist want migratory workers to come for the month required to pick the harvest and to move on when it is over,” he wrote in the Nation. “If they do not move on, they are urged to with guns.” During one trip to the San Joaquin Valley, it rained for sixteen straight days. Nearby rivers and lakes overflowed until floodwaters pummeled the squatter encampments, leaving isolated families on the brink of starvation. “The water is a foot deep in the tents and the children are up on the beds and there is no food and no fire,” Steinbeck wrote to a friend. Seeing the catastrophe up close, he ditched his pen and notebook and helped rescue stranded families, “sometimes dropping in the mud from exhaustion.” Steinbeck would end The Grapes of Wrath with a biblical flood inspired by this experience.

California has undergone radical transformations since the publication of The Grapes of Wrath. For one thing, the state is a lot more crowded. Bakersfield had fewer than 30,000 people in 1940; today, it is home to nearly 370,000. But three-quarters of a century later, if Steinbeck were to return to the San Joaquin Valley and listen to the stories of today’s migrant farmworkers, he would still find much that sounded familiar.

Like the Joads, Bello comes from a region where farmers have long struggled to eke out a living. The village of San Francisco de Asís, where Bello was born and raised, is in the heart of the Mexican state of Puebla, part of a broader area known as the Mixteca. Growing up, Bello and his family grew their own food—mostly rice, beans, and squash—and raised their own goats and chickens. He attended school, which ended at third grade, then graduated into a life of work at the age of seven. Because the Mixteca’s climate is so dry, the soil isn’t all that fertile. Eventually there was an exodus, with villagers heading to first Mexico City, then farther north, across the border. When they returned to San Francisco de Asís, Bello says, they were impossible to miss. “People were building beautiful houses, buying new cars,” he remembers. “Suddenly they had all this money.”

In 1982, at the age of twenty-one, Bello traveled to the border; his wife, Salvadora, and their four young children stayed behind. He rode an inflatable raft over the Rio Grande and into what he hoped would be the start of a new, more prosperous life. In Houston he joined a friend and wound up living with up to ten others in a one-bedroom apartment, where they slept in rows on the living-room floor. Sometimes he found work as a roofer, but more often he spent his days carting away trash from construction sites. Both jobs paid four dollars an hour. After two years, Bello realized he was nowhere close to prosperity. “I thought I could stay here for a little while, come back to Mexico with the savings, and live good for the rest of my life,” he says. But saving money proved difficult, and he missed his wife and children. He returned to his village having learned that he didn’t much care for city life.

The little money he had earned went quickly. One day, news arrived that companies needed workers to pick grapes in the state of Sonora, near the US border. He went north again, this time with Salvadora, leaving their kids with his parents. Once the season finished, they crossed through Mexicali and into California, joining his sister in Coachella, where the grape harvest was getting underway. In both cases, Bello was part of a large group of slow-moving migrants. He never saw a border-patrol officer. He laughs at the memory today, feeling lucky.

Thus began his life working California’s grapes. The season starts in the Coachella Valley, an impoverished agricultural region that also includes the glitz of Palm Springs. From summer to early fall, the harvest shifts to the San Joaquin Valley. Running inland, and curving with the state, the San Joaquin Valley accounts for most of California’s $46.4 billion agricultural industry. Almonds, oranges, tomatoes, garlic: Everything seems to flourish in the valley’s rich soil. In Kern County, at the valley’s southern edge, more grapes are grown than anywhere else in the country. The 2013 harvest—the most recent one for which data is available—brought in $1.8 billion. Grapes now cover more than 100,000 acres in the county, an area more than three times the size of San Francisco.

Moving between Coachella and Kern County, Bello soon learned an unavoidable fact: Migrant farmworkers earn about as much money as they need to continue being migrant farmworkers. So they stocked up on goods when work was steady—waist-high drums of vegetable oil, giant packages of toilet paper—in order to make it through the off-season.

Slowly, Bello’s situation improved. He took a short-term job planting pine trees in Oregon for a lumber company, scrambling up wet mountains for $12 an hour. In 1986, Congress passed the Immigration Reform and Control Act, which allowed more than 1 million agricultural workers, Bello and Salvadora among them, to become legal residents. Once they established their residency, the couple petitioned the US government to bring their children north. When their two oldest sons arrived, aged fifteen and sixteen, they joined their parents in the fields, adding much-needed paychecks. Now all six of his children live in the United States. Four work in grapes, one mows the greens at a Palm Springs golf course, and their eleven-year-old daughter, Sujeny, lives at home. “Compared to Mexico, we definitely have a better life,” says Bello. He has never regretted the decision to come.

Still, worries about money are never far away. After Sujeny’s birth, Salvadora cut down on her hours in the field and now mostly cares for the children of farmworkers, earning $10 a day per child. Bello, meanwhile, estimates that he typically makes about $15,000 a year in grapes. Life on the road presents its own costs and challenges. Bello has lived in motels, campers, apartments, and labor camps. The conditions are usually crowded and rarely cheap, as the influx of migrants during harvest season drives rents up (a simple garage, for example, costs as much as $800 a month). For many years, most of Bello’s earnings were wiped out by the rent.

The problem of migrant housing in California is not a new one. The state that depends on migrants to harvest its agricultural bounty has never found a way, or the will, to properly house them, so they squeeze into whatever slivers of shelter they can find. It was this very problem, in fact, that had brought Steinbeck and his bakery truck to the San Joaquin Valley. Three years before The Grapes of Wrath was published, he reported on the housing crisis caused by the hundreds of thousands of Dust Bowl migrants streaming into the state. Writing for the liberal San Francisco News, he described a visit to a squatter camp, where he found a family who had built a cardboard home that “[W]ith the first rain … will slop down into a brown, pulpy mush.” A neighboring family lived inside a tent “the color of the ground,” whose tattered canvas flaps were “held together with bits of rusty baling wire.” Their four-year-old son had died two weeks earlier of malnutrition. A third family had constructed a shelter from willow branches and slept under a piece of carpet.

In response to the housing crisis, the federal government built a series of camps throughout the state, meant to shelter migrants and encourage a sense of community. One of the earliest camps—and certainly the most famous—was the Arvin Migratory Labor Camp. Built in 1935, and located ten miles southeast of Bakersfield, the Arvin camp was where Steinbeck first came to learn about the Okies. The camp was a revelation for Steinbeck, who partially dedicated The Grapes of Wrath to Tom Collins, the camp manager who served as his tour guide of the San Joaquin Valley. In the face of so much suffering, the camp offered proof that the government could actually do something to help.

The camp, which Steinbeck called “Weedpatch,” after the nearest local community, is a key setting in the novel. The Joads arrive at Weedpatch after having been chased out of a squatter encampment by a trigger-happy deputy. Thus far in the book they have endured one calamity after another, but when they pull their jalopy into the camp, their luck finally seems to change. A clean spot is available for a dollar a week, along with hot showers and Saturday-night dances. The rules of the camp are made and enforced by an elected council of farmworkers. Best of all, cops aren’t allowed inside without a warrant.

It was at the Arvin camp that I first met Bello. He was sitting on a folding chair outside his apartment and gazing across the yard into another summer afternoon turned sepia by the smog. The camp has operated more or less continuously since the Depression, dedicated to housing farmworkers on the road. The original tents are long gone, replaced by barracks-style duplexes that, while as charmless as any suburban subdivision, are clean and safe. (One advocate for migrants called it a “Hilton for farmworkers.”) Free daycare is provided onsite, with early-morning hours to accommodate farmworker schedules. The vast majority of its residents were born in Mexico. Most travel from Coachella, others from Texas; a few hardy families commute all the way from the interior of Mexico each summer. Word about the camp tends to spread quickly in social circles. About a dozen families from Bello’s hometown live here.

At Arvin, Bello pays $11.50 a day for a four-bedroom unit, and he considers the migrant center “a blessing from God.” Most farmworkers aren’t so lucky. Over the last several decades, housing set aside for migrant farmworkers across the state has been disappearing. According to a 2014 report published by Don Villarejo, founder of the California Institute for Rural Studies, one in five California growers claimed to provide housing for seasonal employees in 1986; by 2012, only 3.6 percent said that they did. Meanwhile, registered farm-labor camps, which numbered about 5,000 in 1964, stood at less than 1,000 in 2000, the last time they were surveyed. “They are forced to double, triple, quadruple up,” says Villarejo. “It’s not unusual to visit a place like East Salinas and see mattresses lined up against the wall during the day. That’s because at night fifteen or twenty people will be sleeping there.”

The government does provide some help. The Farm Labor Housing Program, a program of the USDA, operated close to 5,600 units in the state as of 2011. California’s Office of Migrant Services also runs twenty-four centers, like Arvin, which add another 1,883 units. But with an estimated 800,000 farmworkers in California, these projects offer housing for less than 1 percent of the workforce. Even if more government-subsidized units are built, undocumented immigrants—who make up more than half of the workforce in California’s fields—would be barred from living in them.

And while the ditch-bank squatter camps of the Depression were impossible to ignore, signaling desperate circumstances to anyone who passed by, today’s housing crisis is tucked away. One study of seven agricultural communities in California found that 10 percent of farmworkers lived in what researchers called “informal dwellings,” which included garages, sheds, barns, and abandoned vehicles.

Trailer parks represent a relatively affordable alternative. On a bright May afternoon, Fausto Sanchez, a farmworker turned advocate, gives me a tour through several trailer parks near the Arvin camp. A few of the units appear relatively clean and well kept, but many look like they should have been retired long ago. I point to a trailer with broken windows and a wall with a gaping hole, which has been covered over with cardboard—surely that one is empty. Sanchez nods toward an old truck parked in the driveway.

None of this is shocking to Sanchez. Short and with a grave-looking face, he came to the US from the Mexican state of Oaxaca as a teenager, speaking only the indigenous language of Mixteco. One of his first jobs was picking oranges in Chandler, Arizona. He and his companions didn’t have a place to stay, so they slept under the groves, fashioning shelters out of cardboard boxes and plastic trash bags. They bathed in an irrigation canal. “It sounds bad, but it didn’t feel that way at the time, because I didn’t know anything else,” he says. Seeking a way out, he eventually learned Spanish and English, earned his GED and an associate’s degree, and is now on the staff of California Rural Legal Assistance (CRLA), where he assists indigenous Mexican immigrants.

This newest wave of immigrants, who frequently don’t speak Spanish, now make up one-quarter of California’s farmworkers. In 2010, researchers working in collaboration with the CRLA published a major study of this mostly ignored population. They found that indigenous migrants lived in conditions that were “consistently appalling” and faced a wide range of labor abuses, from foremen who randomly docked their pay to fields that had no drinking water or bathrooms. One-third reported earning less than the minimum wage.

“They are the invisible of the invisible,” says Sanchez. “A contractor will ask them, ‘How much did you make a day in Mexico?’ ‘Oh, eighty pesos’”—the equivalent of a bit more than five dollars—“‘Well, I’ll pay you more than that!’” Sanchez spends much of his time reaching out to Mixteco-speaking families, documenting wage theft and building pressure on crooked labor contractors, some of whom, he says, pay as little as $25 for eight hours of work. Adjusted for inflation, that’s less than what farmworkers in the San Joaquin Valley made in Steinbeck’s day.

When The Grapes of Wrath was published, those sympathetic to migrant farmworkers hoped it would trigger long-overdue improvements. Steinbeck certainly wished it would do so. Upon finishing the book, Eleanor Roosevelt toured a decrepit shantytown in Bakersfield, telling a scrum of journalists that she “never believed that The Grapes of Wrath was an exaggeration.” The film adaptation of the book was released in 1940, staring Henry Fonda as Tom Joad, and was nominated for seven Academy Awards. How could all this attention not help the cause?

It seemed like it would. In the fall of 1939, emboldened in part by the book, a scrappy cannery-and-farmworker union called for higher wages for cotton workers across the San Joaquin Valley. Growers balked, and the ensuing strike became a cause célèbre, with Hollywood moguls donating funds and clothes. Woody Guthrie visited, singing to the strikers before bedding down for the night among them. Growers and law enforcement kept a close eye on the workers as they picketed the fields each morning. Soon enough, as with many of its kind and time, the strike was violently crushed. At one union rally, farm owners waded into the crowd swinging clubs and pickaxes. Through it all, California’s liberal governor, Culbert Olson, failed to intervene.

It wasn’t until the late 1960s, and the rise of Cesar Chavez’s United Farm Workers, that change once again seemed possible. They captivated the nation with strikes and a national grape boycott. Their biggest target was a company called Giumarra, then and now the largest table-grape grower in the country—and Bello’s current employer. By 1970, after a five-year fight, most of the grape growers had caved in. John Giumarra, representing growers in the Delano area, where the union was based, signed a contract with the UFW that granted workers $1.80 an hour—$10.89 in 2015 dollars—with multiple benefits, including payments into a health-care fund. It was hoped that these contracts would mark the beginning of a march into the middle class for California’s farmworkers. At the signing, Giumarra’s son, also a grower, echoed the language of the union, calling the contracts both “an experiment in social justice” and a “revolution in agriculture.”

By all appearances, that experiment has failed. Bello, a veteran employee of twenty-seven years with Giumarra Vineyards, earns only $9.50 an hour. Still, he feels fortunate, since other companies in the Arvin area pay even less. (Many of the farmworkers I spoke to earned just $9 an hour, California’s minimum wage.) And even on hot days, when other companies dismiss their workers early, Bello says, he’s worked full, nine-hour shifts. “If we were always stopping, we wouldn’t make enough money.”

If the earlier obstacles to organize farmworkers are relatively easy to explain—brute opression and an indifferent or hostile government—the factors that led to the downfall of the United Farm Workers are more complicated. Enduring hostility from growers and politicians was complicated enough. But over time, Chavez grew paranoid and power-hungry, viewing strong farmworker leaders as a threat to his rule. Eventually, the union turned its attention away from organizing in the fields, and today the consequences of that decision are plain to see. Philip Martin, an expert on California agriculture and professor at the University of California, Davis, estimates that the union has just 3,300 active members, and it doesn’t represent a single table-grape worker. Even today, in an era of dramatic inequality that has sparked a number of ambitious campaigns—an effort to organize fast-food workers, proposals to raise the minimum wage to $15 an hour (which just passed in Los Angeles)—no one has been audacious enough to launch a renewed organizing drive in California’s fields.

Earning a quarter or two above the minimum wage has kept Bello far from the middle class, but it never tempered his ambition to own a home. “I just couldn’t stop thinking about it,” he says. “It didn’t seem like it was possible, but I knew there had to be a way.” In the late 1990s, he and Salvadora, already living on a tight budget, somehow made it tighter, putting away small amounts here and there. They caught a big break when they arrived at Arvin camp, where he landed a spacious apartment for just ten dollars a day, which allowed them to squirrel away more money. It took a while, but after years of scrimping, they’d saved about $30,000.

Their second big break came in the form of the Great Recession. What was a disaster for many proved an opportunity for Bello. Housing values in Coachella plummeted. Foreclosures surged. A four-bedroom home that had fetched $315,000 in 2006 was being sold by a bank in the spring of 2009 for $154,000 and was everything Bello had hoped for—modern and spacious with a lush backyard. He and Salvadora scrounged extra money from family members, put down $35,000, and moved in. It was, Bello says, one of the happiest moments of his life.

Eight days later, Bello collapsed. Salvadora found her husband on the bathroom floor, lying still with his eyes wide open. “I truly thought he was dead,” she says. She doused rubbing alcohol on his face to revive him, and after several tense seconds he finally regained movement, with blood coming out of his nose and mouth. They didn’t know it at the time, but Bello had suffered a brain hemorrhage.

As Bello struggled to sit up, Salvadora said she was going to call 911. No, he said, don’t call for an ambulance. He was in a foggy state, but he was clear about one thing: He didn’t want to lose his house. Neither Bello nor Salvadora had health insurance. “I knew how quickly our money would run out if I went to the hospital, and how we would lose everything,” he says. “I couldn’t let that happen.”

He called his eldest son, who drove him across the border to a hospital in Mexicali, some ninety minutes away, where he hoped the treatment would be cheaper. Doctors at the Mexicali hospital diagnosed the hemorrhage, but then, according to Bello, wanted $50,000 for the operation. He didn’t have the money, of course, and so they recommended that he be transferred to a hospital in San Diego. An ambulance took Bello back to the border, which he was wheeled across on a gurney into the US. He was then loaded into another ambulance and rushed to San Diego. After surgery, he spent nearly a month recuperating in the hospital. That first surgery was in March, followed by another in April. By May he was working in the fields.

This seemed like an unusually fast turnaround. “That’s what I was worried about,” he tells me. “That I wouldn’t be able to work. But I asked God to give me the strength.” Though he doesn’t admit it, it’s likely he returned to work against the doctor’s orders; soon afterward, his head became infected, requiring a third surgery. He pulls off his hat, motioning to an indentation above his brow line, where a portion of his skull was removed. “I’m fine,” he says, laughing at my grimace. “I kept my home for the family, so it’s all fine.”

In the end, his worries about money proved unfounded. He and Salvadora’s incomes were easily low enough to qualify for Medi-Cal, the state’s Medicaid program, which paid for the surgeries and hospital stay. Bello, whose own name means “beautiful” in Spanish, took it as yet another sign that life was good.

On Labor Day, near the end of the harvest season, I find Bello at home, in his usual spot where he likes to relax, seated on a lawn chair and looking across the yard at the Tehachapi Mountains in the distance. Aside from a few children on the playground, the camp is mostly empty since, despite the holiday, most farmworkers are in the fields. Giumarra has given its workers the day off. I grab a chair and Bello hands over some grapes he packed a few days ago, which pop coldly between my teeth.

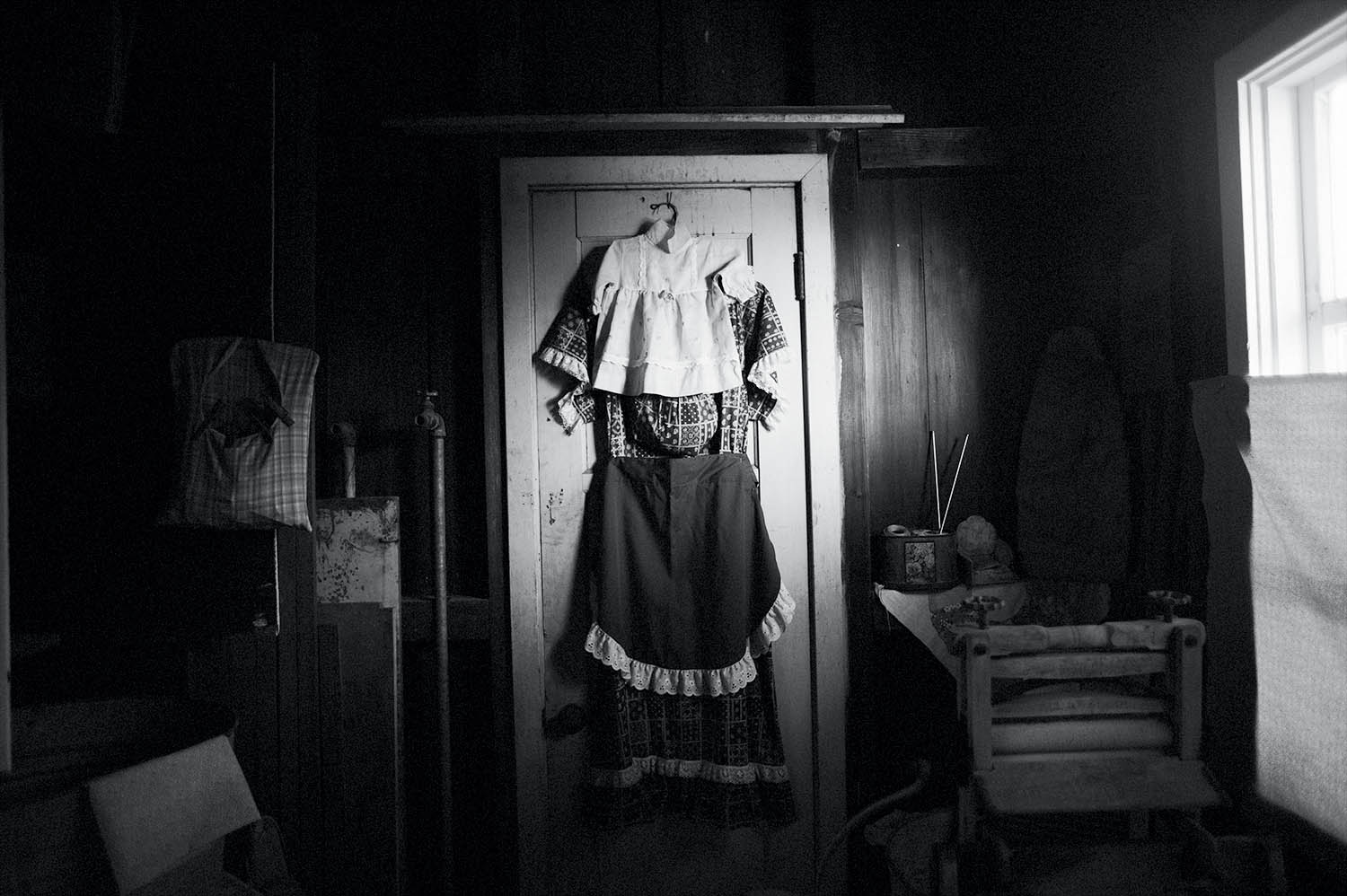

Our conversation turns to the camp. Over the years, Bello has heard a number of stories about its history. One of his daughters had gone online and come back with intriguing bits of information: that the camp had been a prison of sorts, or perhaps a cemetery. I describe what I know. Like most current residents, Bello hasn’t heard about its past fame or The Grapes of Wrath. “I have seen people working over there,” he says, pointing to three wooden buildings near the camp entrance, which are fenced off. “But I didn’t know what they were doing.” The three buildings are the camp’s original post office, social hall, and library, where a greasy copy of the banned book was once passed between callused hands. A volunteer group called the Dust Bowl Historical Foundation—some of whom were born in the camp—is currently renovating the structures.

We walk over to have a look. Inside the library, a dusty phonograph sits on a desk, next to a print of the iconic Dorothea Lange photo “Migrant Mother.” A pair of rusted roller skates are tucked away in a corner. We head over to the social hall and peer through its windows at the wood floors, the beams that run across the ceiling, the stage at one end. Here is where Okies once prayed and danced, fell in love and organized a union.

As we leave we pass by a cement plaque, dedicated in 2002 by then Oklahoma Governor Frank Keating, which reads, from the people of oklahoma—the okies—who found a home here and helped build california. I provide a rough translation for Bello, who looks at me quizzically.

“Oklahoma?” he asks. “The farmworkers were americanos?”

Along with its details of suffering, this incongruent image was another reason why The Grapes of Wrath elicited such sympathy. For a moment, as Mexican laborers were replaced by the arrival of Dust Bowl migrants, there was a major demographic shift in the fields, and it was this shift that Steinbeck chronicled. That the Joad family was white caused many readers to finally care about what had always been present.

This article was reported in partnership with The Investigative Fund at the Nation Institute.

Brian L. Frank’s photography project Downstream: The Death of the Colorado is held in permanent collection at the United States Library of Congress, and his street-level look at the drug war in Mexico, La Guerra Mexicana, has been recognized with international awards.