Will Aung San Suu Kyi Ignore the Rohingya?

Editor’s note: This is a 2-part series on the Rohingya in Burma. Read the first post here. For more about Burma, see our Summer 2012 issue, Burma Exhales.

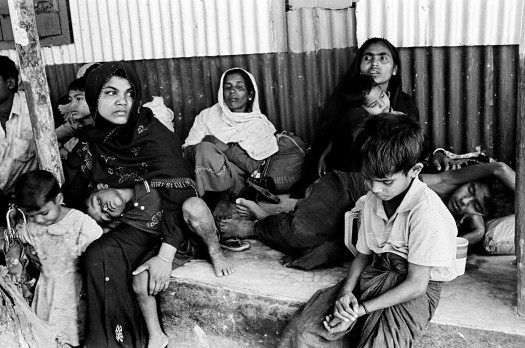

The Rohingya in Bangladesh: A dozen or more family members often live in the same hut, built of leaves, twigs, mud, and scrap plastic and wood. Aid workers say conditions in the camp are some of the worst they have ever seen.

Thirty years ago this October, the military-run government of Burma enacted the 1982 Citizenship Law. The Law established three types of citizenship categories, which provides “full” citizenship only to those from Burma’s 135 recognized “national races.”

For most of the larger ethic groups in Burma, the Law confirmed their right as citizens of the Union. For others, specifically the some 800,000 Muslim Rohingya living in the Rakhine State of Burma, the Law formalized their non-existence in the eyes of the Burmese authorities and many others in the country.

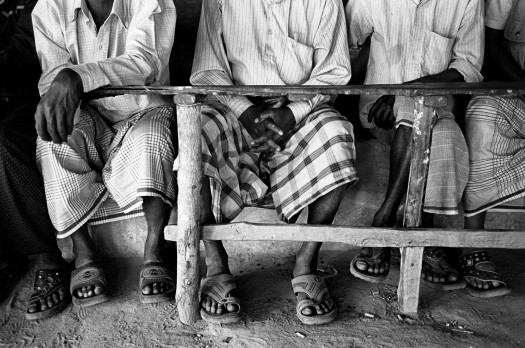

Many Rohingya say that until they are granted citizenship and other basic rights, they will continue to leave Burma for Bangladesh and other countries in the region. Yet, in Bangladesh, life continues to grow more difficult. A group of Rohingya men haven’t worked in over a week because they fear being arrested if they leave their homes.

In June 2012, ethnic violence between the Muslim Rohingya and Buddhist Rakhine communities in the Rakhine State of western Burma—particularly in the main city of Sittwe—resulted in the reported deaths of over 80 people, the displacement of thousands, and the large-scale destruction of property. Violence was perpetrated by both communities against each other. Eventually, the violence spread to the North Rakhine State, where government troops and members from the Rakhine community turned against the Rohingya. The violence received widespread attention from the international press and human rights groups. It thrust a light on an ethnic tension and divide between the communities that has been festering for decades, as well as the deep-rooted racism and intolerance against the Rohingya that has been largely manufactured and perpetuated by the Burmese military government since the 1960s.

Over the past year, the media, the diplomatic community, and world leaders have turned their eyes and attention to Burma. Recent reforms have been heralded and have paved the way for the outside world to engage with the country. Restrictions on the freedom of the press have eased. Democracy and freedom icon, Aung San Suu Kyi, is sitting as an elected member of parliament. And, in a way not seen in decades, the U.S., UK, and the EU are courting Burma as an “opportunity” rather than as a diplomatic eye sore controlled by a brutal military junta.

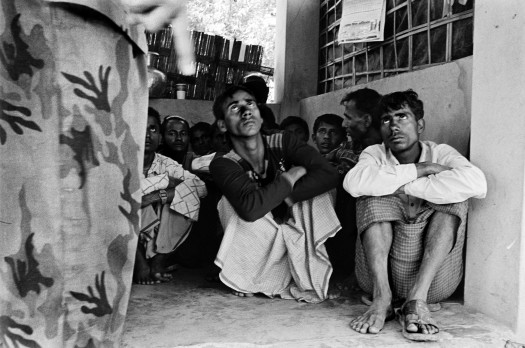

In Burma, Rohingya are denied the ability to travel to find work. As the situation in southern Bangladesh becomes tenser, Rohingya in both countries pay brokers to smuggle them by boat from Bangladesh to Malaysia. Several thousand Rohingya have made the perilous journey in the last year, but recently, Bangladesh authorities have stepped up their efforts to apprehend Rohingya before their journey begins. BDR troops caught this boat in the middle of the night just outside of the town of Teknaf on February 17. The boat was ferrying a group of Rohingya to a larger boat waiting out in the sea.

But the recent violence in Rakhine, and the response or lack of response from the Burmese government and others, has left many questioning the legitimacy of these recent reforms in relation to human rights—as well as the position of those who have been seen to hold the moral authority in Burma.

In response to the ethnic violence, Myanmar’s President Then Sein said in a statement on July 12 that the Rohingya were not an ethnic nationality of Burma and were not wanted. In his statement he proposed for all 800,000 Rohingya in Burma to be placed in UNHCR monitored refugee camps or deported to third countries who would take them.

While on a tour of European nations this past summer, Aung San Suu Kyi avoided all questions about the Rohingya, only saying, “I don’t know” when asked whether the Rohingya should be extended Burmese citizenship.

And on Sept. 3, hundreds of monks walked the streets of Mandalay in support of the President’s suggestion to deport the Rohingya or hold them in camps.

A group of twelve Rohingya men, mostly between the ages of 19 and 28, were pulled off of a bus at a BDR highway check point the morning of Feb. 19. The men had crossed into Bangladesh from Burma earlier that morning. They traveled to Bangladesh to get on a boat to Malaysia. Bangladesh authorities pushed the entire group back to Burma the same night.

Given the President’s proposed and radical solution, Aung San Suu Kyi’s silence, and Burmese public support of the anti-Rohingya sentiment, one thing is for sure: The question of the Rohingya’s nationality status and “where they belong” is a huge (and true) test of where people stand on finding a solution to their plight. Nothing can be more diplomatically turbulent or controversial than the international community pressing or challenging a sovereign country like Burma (especially in an infancy stage of democratic reform) about how they determine who is a citizen and who isn’t, and the make up of their “national identity.”

Aung San Suu Kyi is in a difficult situation. As someone who has championed freedom, human rights and the rule of law for all people in Burma for some 25 years, many have criticized Aung San Suu Kyi for her silence. While no one can question the sacrifice and effort she has made in her noble cause for a free and democratic Burma, Suu Kyi’s position since becoming an elected MP has had to change. She is no longer under house arrest. She’s now officially in the game. She’s an elected official, which makes her vulnerable to political pressures and backlashes.

On July 25, in her inaugural speech to the Burmese Parliament, Aung San Suu Kyi spoke of the importance to protect the rights of Burma’s ethnic communities. “To become a truly democratic union with a spirit of the union, equal rights and mutual respect, I urge all members of parliament to discuss the enactment of the laws needed to protect equal rights of ethnicities,” she said.

This week, as she visits the United States, she will be receiving many top awards for her mission toward human rights and democracy, including the Congressional Gold Medal from U.S. Congress, the Global Vision Award from the Asia Society, the 2012 Democracy Award from National Endowment for Democracy, and the Global Citizen Award from the Atlantic Council. And with each acceptance speech, many will be eagerly waiting or wondering whether she will say something of substance about the most pressing and severe situation of human rights in her country today, that of the Rohingya and whether or not they will be accepted as citizens in Burma, the country of their birth.

A group of twenty Rohingya is detained by BDR right after their boat crossed the Naaf River from Burma. Fifteen are women and children, and several of the children are sick. BDR pushed the entire group back to Burma the same night, but many in the group returned to Bangladesh the next day.

About the Author

Greg Constantine is an award-winning photojournalist from the U.S. currently based in SE Asia. For the past six years, he has worked on a project documenting the plight of the Rohingya from Burma. His second book: Exiled To Nowhere: Burma’s Rohingya was just published. Also, a groundbreaking iBook, In Search of Home, exploring the issue of global statelessness—a collaboration between Constantine, writer Stephanie Hanes and the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting—was also released. Visit Exiled to Nowhere to learn more. Part of the reporting for work on the Rohingya was provided by a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.