The Soft Knock

The helicopter touches down before sunrise on Monday morning, October 5, in a freshly tilled field in the middle of Afghani nowhere. Two platoons fan out silently from the tail of the Chinook, securing a temporary perimeter and running communications checks. One platoon takes the high ground on the valley wall, providing overwatch, ready to react in the event of an engagement. The other platoon will walk through the villages of the valley, knocking on doors and searching compounds with the support of the Afghan National Police (ANP) and Afghan National Army (ANA).

I’m with a battery from the 4-25 Field Artillery, one of the units that make up the 10th Mountain Division’s Task Force Spartan, on a two-day foot patrol in the Jalrez Valley, near FOB Airborne, in Wardak Province, about 20 kilometers from Kabul. Despite their Field Artillery designation, these troops have been operating as an infantry company throughout their tour. They have been patrolling, slogging up and down goat trails, searching houses, and directly engaging the enemy instead of firing off their Howitzers from the relative safety of the FOB.

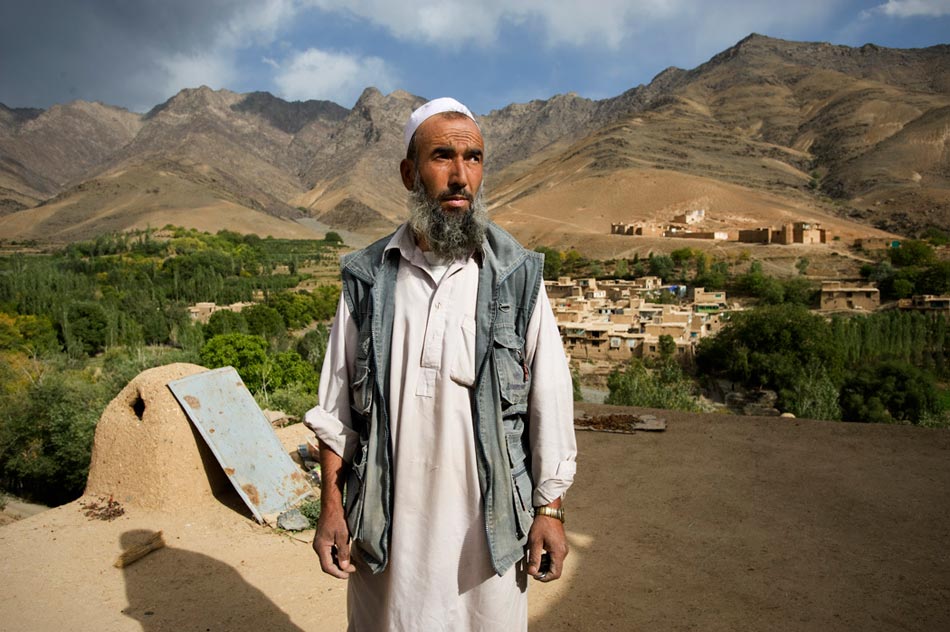

Sunlight reveals a lush valley floor, thick with apricot and apple groves and willow trees, cross-hatched by gurgling irrigation channels and low stone walls. The place is striking in its simple beauty—damp, green, and silent—especially compared to the dust bowl of Kabul, where a carpet of khaki-colored haze stretches as far as the eye can see. But this is no nature walk. A drone’s buzz fills the valley walls. The commander’s radio scratches. The soldiers’ loaded weapons clink against their body armor. Their boots crunch brush underfoot. They are looking for information on a local Taliban leader believed to have planned an IED attack in July that killed four of the unit’s members.

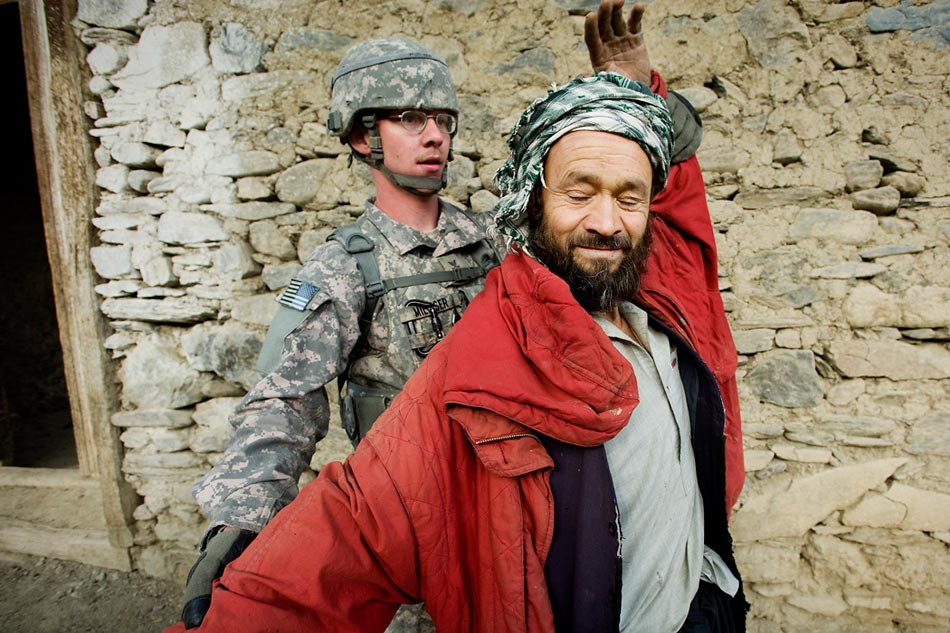

The soldiers do their first “soft knock” of the day just before 6 A.M. The soft knock approach grew out of the failures of the cordon and search tactics implemented by U.S. forces in Iraq. These so-called hard knocks alienated the population while providing negligible intelligence. With the soft knock approach—always conducted alongside ANP officers—the owner of a property must give his permission to the troops at his door before they can come in and search the premises. If he says no, the police secure a warrant.

A middle-aged man cracks the wooden door and immediately asks for permission to gather the women out of sight, but he seems unsurprised, unafraid. Once the women are safely cloistered, the man returns and invites the soldiers in. The exterior door gives way to a sprawling compound, entirely constructed of mudbrick and wattle, fortified with bits of gravel and straw. Flowerpots hang from a second story balcony railing, painted turquoise to match the window frames. Pear trees heavy with fruit flank the entryway.

Without warning, a hobbled old man comes around the corner, surprising the soldier guarding the door. The soldier yells, “Stop!” The old man inches forward on his cane. “Stop!” the soldier yells again. The old man stops and raises his head. He stares at the soldier for a moment, then resumes his shuffle to the door. The soldier gives up. Two goats burst out of the door and rush for the fields. The man who first greeted us sends a young daughter running off to retrieve them. She cries as she runs, hiding her face in a long pink shawl. I can’t tell if she’s crying out of fear or humiliation.

The soldiers continue down the valley all day, searching one compound after another. They register the fingerprints and photographs of fighting age males in a handheld computer. Soon the languorous afternoon saps their motivation, and the mood loosens. But when we come to a large village spanning a dry riverbed and climbing both valley walls, the jokes stop. “This village gives me the heebie-jeebies,” says one squad leader. The old men crouch beside their doors, leering. The rooftops stare down on us, and the whole place seems suddenly claustrophobic. Dozens of children pour out to stare at us. They offer walnuts. “No, thank you,” one soldier says, gently. He fumbles for the phrase in Pashto. “Teshukr,” he says, after a few halting tries.

Nothing happens. One of the compounds belongs to the target, but he isn’t there. No one expected he would be. His family isn’t there either. “Everyone is always in Kabul,” a soldier explains. This is always the response to soldiers’ questions about Taliban suspects. They have not gained trust in the valley.

The soldiers move across the riverbed to search two last compounds. They find a spider-hole behind one with a couple of rocket-propelled grenade rounds inside. “Whose are these?” one of the soldiers asks the owner. “The Russians put them there,” the man replies. (This is the other standard reply. “Either the Russians put it there or they’re in Kabul,” a soldier tells me.) They blow the RPGs in place and leave the man with a warning: “If we ever come back here and find stuff like that again we’re going to level the whole house.” The soldiers have the power to do no such thing, and the man probably knows it.

We move south down the valley, away from the village, toward an open field where we’ll spend a freezing night huddled on the damp ground. Winter is coming, the end of the fighting season, the end of Task Force Spartan’s tour.

As darkness falls, Staff Sergeant Mitchell is organizing his soldiers, planning his area of the company’s defensive perimeter. He’s the only one who still has any energy after the day’s patrol. Mitchell is a natural leader—about six feet tall, lean and muscular. He is also the only black soldier in the platoon. Earlier, he told me about a plan he had to go to Officer Candidate School and make a career out of the Army. If he could make it to Lieutenant Colonel, and have his own Battalion, he would stay in thirty years. That was before this most recent tour. Now Mitchell is planning to get out of the Army altogether.

“Hey, I just realized that’s the backside of the mountain we see from our base,” he says, looking down the valley. We’re only a few kilometers from the isolated Combat Outpost (COP) where the soldiers are stationed. “Consider yourself among the lucky few,” I joke, “to have seen the mountain from both sides.”

“Man,” he says, “I’ve seen too many sides of too many fucking mountains.”