Passover in the West Bank

Samaritans perform their traditional slaughter of the Passover sacrifice ceremony at Mount Gerizim, north of the West Bank town of Nablus.

Photographs by Ammar Awad / Corbis

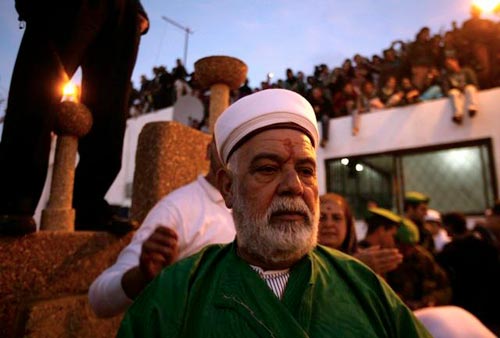

The Samaritans have thirteen names for Mount Gerizim, which rises four hundred meters above Nablus, on the West Bank, including the House of God, Mountain of the East, the Chosen Place, Gate of Heaven, the Everlasting Hill, Bethel, One of the Mountains, and The Lord Will Provide. And it is on the ridge below this sacred mountain, in the village of Kiryat Luzah, that they celebrate Passover, a ceremony that each year draws thousands of spectators, Israeli and Palestinian—always without incident, according to the elderly priest who invited me to witness it. He was of the opinion that the Samaritans, the world’s smallest religious-ethnic group, could build a bridge of peace between Israelis and Palestinians—the first constructive idea that I had heard on the subject in my travels through the region—and so one day in late April I arranged to drive from Jerusalem to Kiryat Luzah with a young Palestinian named Maath, who took an interest in the Samaritans. Summer was coming on—hay was baled in the fields—and as we cruised along a winding road built to connect the settlements Maath told me some of his story.

He had returned to his homeland after completing a degree in information technology in Dubai, and what he discovered was that Palestinians fell into one of three camps concerning the occupation: those who were so frustrated that they resorted to violence; those who would give up anything for a peace agreement; and those, like him, who kept pushing for their rights. An Israeli police van sped past, its lights flashing. Maath admitted that this third group was lost.

“If they resist, they’ll be confused with the fanatics,” he said. “And if they go into politics they’ll be confused with the Palestinian Authority, who will give everything away. So they do nothing and wait for magic, like the Americans stepping in to throw the Serbs out of Kosovo.”

The soldiers manning the watchtower and checkpoint at the base of Mount Gerizim eyed the cars approaching the roundabout, stopping some, waving us through, and as we started up the mountain, toward the settlement of Har Brakha, Maath said that he and his friends liked to debate what was permissible in resisting the occupation—whether, for example, it was just to kill soldiers (yes, they agreed), civilians (no), and settlers (yes, if they were armed). The wounded presented a dilemma. Those who vowed to finish them off might not be able to pull the trigger, if it came to that, Maath believed. It was easy to speculate about right and wrong until you were in the heat of battle, when all bets were off. Nevertheless he could understand the frustration that led some of his friends to contemplate killing the wounded.

A Samaritan boy pets a sheep before it is to be slaughtered.

Onlookers crowd the stands surrounding the traditional Passover site.

Har Brakha occupies the ridge leading to Kiryat Luzah, and from the frame of a doorway in a long one-story building under construction a boy watched us pass. Buses were parked at the edge of town, tourists and settlers milled among the soldiers on the main street, and the air was thick with the smell of lambs grazing in a nearby sheepfold. The Samaritans, all 742 of them, had brought lambs to celebrate the account, in Exodus, of the freeing of the ancient Israelites from the slavery of the Egyptians. Passover is a story of survival, which carries particular meaning for a community that in Samaritan lore once numbered in the millions. Persecuted by Jews, Romans, Christians, and Muslims, massacred and assimilated and exiled, by 1901 the Samaritans were down to 152 people, genetic disease was on the rise, and it is a miracle that they survived at all; their five-fold increase in population is a testament to the decision taken to allow men to marry outside the community, providing that the women—Jews, Turks, Russians, and Ukrainians, who answered newspaper ads to move here—convert to the faith. On my first trip to Kiryat Luzah, in March, I was amused to see a bulky blonde-haired woman walking down the street.

“A mail-order bride,” a Palestinian friend explained.

The Samaritans live in two places—on the outskirts of Holon, south of Tel Aviv, and in Kiryat Luzah, the Nablus branch of the community having moved here during the first intifada, in 1987—navigating carefully between Israelis and Palestinians. The Israeli government offers them the same right of return as other Jews, since they descend from the original tribes of Israel, and Palestinians claim them as part of their culture, since they hail from Samaria. One day a year they are the objects of fascination for their warring neighbors, and as we walked by the Center of Forgiveness the talk of a third intifada seemed a distant possibility. It was said that the next battle would begin in East Jerusalem, where plans to build new settlements on Palestinian land continued in spite of Obama administration entreaties to the government of Benjamin Netanyahu to freeze construction. Seven soldiers were marching a man in plastic handcuffs down the center of the street, under the reproachful eye of a settler with an M-16 slung over his shoulder. Three teenagers had been detained by a Humvee parked at the entrance to the Passover site—because they lacked permits, said a man who worked for a cell phone company. Maath pointed to the Israeli flag hoisted above the stands built for the tourists.

“I don’t care how the Israelis define it,” he muttered. “This is the West Bank.”

* * *

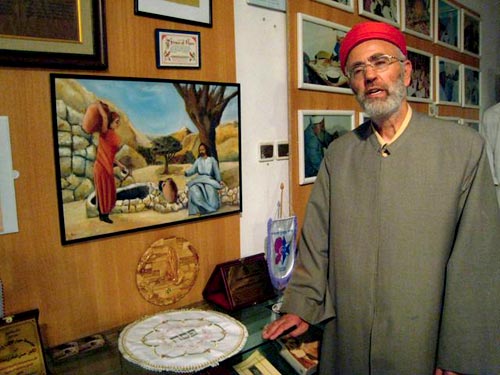

The parable of the Good Samaritan is the crucial New Testament teaching about our obligations toward others, including our enemies. A lawyer asks Jesus what he must do to inherit eternal life, and Jesus tells him to follow the law—to love God with all his heart and mind, and to love his neighbor as himself. And who is my neighbor? the lawyer asks. Jesus answers with the parable of a man traveling from Jerusalem to Jericho, who falls among thieves, is stripped of his clothes, beaten, and left for dead. A priest and a Levite pass him by, but a Samaritan, stopping to help him, bandages his wounds and takes him to an inn, instructing the innkeeper to care for this man, who is his enemy. Jesus tells His disciples to show the same mercy toward others, and this is the parable that the founder of the Samaritan museum invokes when he tells visitors that just as the Samaritan helped Jesus so the world must help its smallest and oldest people.

The museum was located in a stone building adjacent to a factory which supplies tahini to distributors in Brooklyn. On one wall was the Samaritan family tree, which traced the Hebrew Levi tribe from which the Samaritans descend, and on another was a menorah-shaped decoration, with seals bearing the names of all the Samaritan high priests back to Adam—163 generations in all. The museum director was explaining Samaritan beliefs and customs to a group of elderly Israelis, displaying a copy of an ancient Torah scroll (the original is hidden, another scroll having been stolen some years before). We went to the office to speak with his daughter.

Salwa, a tall, pretty woman in a purple blouse and jeans, was completing her degree in English at an-Najah University in Nablus, and if she was uncertain of her speaking abilities she did not hesitate to recite the history of her people, beginning with the Samaritan language.

“Our language, Old Hebrew, is the mother of all languages around the world,” she said. “It is a pure Semitic language, unlike modern Hebrew, which was created in Europe.”

“And this is our Independence Day,” she continued, assuring me that all religions would celebrate it peacefully on Mount Gerizim. She said that the smoke from the roasting lambs must reach God—and that the smell from the fires would last all week. Then she spelled out her full name for me: Salwa Hosny Wasif Tawfiq Khoir Ghazal Salama Kahen, Salwa meaning honey in Samaritan, amuse in Arabic. Her older brother had died in an accident, and when she was born her parents named her Salwa, hoping she would bring them happiness.

It was time for her to go change into a traditional white robe, which by nightfall would be spattered with the blood of the lambs. She promised to look for us at the ceremony.

* * *

My introduction to Samaritan culture took place one winter afternoon in Nablus, in an unheated Ottoman-era horse stable converted into a cultural center. In an office surrounded by glass walls, under a whitewashed arch, I met with a dozen students around a coffee table on which stood a wooden model of Al-Aqsa Mosque, on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, built by a political prisoner. Our discussion turned to the question of identity, and Jako, a bright, twelve-year-old Samaritan with thick glasses, said that his people were the true Israelites—although he considered himself to be Palestinian. He asked me if I had heard of Jesus. Yes, I said—and then he proceeded to read a story, in English, on the birth of the Samaritans:

Being a Samaritan is no different from being a Palestinian. The Samaritans are very famous in some countries for their love of God. Samaritans aren’t one of those people that started their “guild” in the 1920s or in 1120s but they are intact over two thousand years old… We started off as Muslims serving a guy named Faroon until one day his wife told him that some child would grow up and stop his reign of being emperor, so he told the guards to put a plot around the village. It was a decree that every woman was going to give away her baby so he can kill them, but one didn’t listen to him. She was named Maryell. She put her son in a casket and she pushed the casket. One day later Faroon’s daughter found him and named him “Jesus.” Jesus therefore grew up as a king, but one day he killed a gua guard because he was hitting a Hebrew. Jesus was also Hebrew so when he saw the guard he was angry so he killed him. He ran from the village. After 25 years he was walking around a mountain when he saw God. God told him to go back and top Faroon and he did and therefore was the birth of the Samaritans.

A friend in Jerusalem described this story as a surrealist fable woven out of biblical elements, all the “facts” as we know them transformed into something new—an apt description, it seemed to me, of the process by which religious revelation is adapted to changing circumstances.

But Samaritans profess not to have deviated from their original understanding of Torah and practice of their faith. They believe that Mount Gerizim is the holiest place on earth, the site of the First Temple, of Abraham’s near sacrifice of Isaac, of the Messiah’s promised return; they claim to celebrate their three pilgrimage feasts of the liturgical year—Passover, Shavuot (which commemorates God’s gift of the Torah to Moses), and Sukkot (the Feast of the Tabernacles)—in the exact same way as their ancestors; they blame their eternal conflict with the Jews on different interpretations of a history long buried in the sands and of the Torah, the Samaritan version of which includes a commandment on the sanctity of Mount Gerizim.

Late in the afternoon Maath and I climbed the mountain, through red poppies and dry grass, picking our way around a barbed wire fence at the base of the Roman wall, and came to a promontory overlooking Nablus, an inland sea of white buildings stretching to the mountains across the valley. Clouds were moving in, and the wind was rising. I struck up a conversation with some Orthodox Jewish students whose teacher told me that the Samaritans destroyed the Second Temple, believing that it should not have been rebuilt in Jerusalem—an extension of the argument, perhaps, that its destruction by the Romans in 70 CE was the result of divisions among the Jews, of the baseless hatred that will not be resolved until the Third Temple is raised.

Archaeological excavations of Mount Gerizim, begun in 1984, have uncovered the ruins of a synagogue, a temple to Zeus, and a sixth-century Byzantine church built by Justinian, where a guide had invited Christian pilgrims to sit on the low stone wall surrounding the nave.

“Even if you don’t believe in Jesus Christ,” he said with an accent that I could not place, “what I tell you in the next fifteen minutes should convince you to believe.”

He asked for two volunteers, and two American men, who looked like a father and his son, stepped forward to play the roles of the sinner and the sheep.

“The sheep is a good sheep,” said the guide, patting the younger man on the back, “and the sinner”—he smiled at the older man—“is just a sinner, who brings his sheep from the north. I am the priest who must examine the sheep. Are his teeth good? Is he blameless? Then the sinner lays his hands on the sheep, and all its blamelessness, all its goodness, flows into him, so the sheep must be sacrificed. Give your applause for the sheep and the sinner.”

Samaritan men slaughter a sheep during the traditional Passover sacrifice ceremony.

And so they did, whereupon he arranged the crowd into two circles, one to represent the prison of sin, the other the prison of the realm of righteousness.

“Sarah,” he said, singling out a middle-aged woman, “is in the prison of sin despite her good deeds, and now Jesus Christ comes to offer her an exchange, to go the good prison. Jesus, being perfect, the second Adam, did something that Adam couldn’t do. Only when we live in the spirit can we be free. It’s the law of double jeopardy. If she is fixed on Jesus, she cannot go into the prison of sin, of the law, because she is free from the law, from the prison of sin.”

With that he urged the pilgrims to hurry downhill to the ceremony. I fell into step with a woman from Atlanta, who said that the Lord had led her to Jerusalem to work in a prayer center. It was not clear to me what the guide had said to convince his followers to believe in Jesus, and this woman shed no light on the meaning of his demonstration.

“Am I supposed to be leading the way?” she said lightheartedly. “Not a good idea.”

* * *

The gate to the Passover site was guarded by soldiers, and it was some time before Maath could find a priest to vouch for us. “What the fuck,” said a Samaritan in white boots, muscling through the crowd, one of the six men trained to perform the ritual slaughter. Boys were feeding branches of trees into the fire pits; soldiers and journalists took photographs; the host of Sleepless in Gaza and Jerusalem, a web production company (www.youtube.com/sleeplessingaza) filming ninety episodes in ninety days, said that her viewers would be surprised to see her here, since she was a vegetarian. Presently the lambs were led to a long cement trench, on either side of which the men and boys dressed in white (the color that they wore on their flight from Egypt) stood side by side, straddling the frightened lambs, holding them between their legs as the high priest and the elders assembled on stage. The men hung grapples from the pair of metal rods running the length of the trench, slipped knives into their pockets, and waited anxiously. One deaf mute slapped another, attempting to provoke a fight until a teenager stepped in to stop him. A settler adjusted his pack, checked his rifle, surveyed the stands. Three soldiers near me stood in pensive silence; and when the prayers began, the Samaritans lifting their upturned hands to the sky, the radio man gave me a little smile. The chanting grew louder and louder, the rolling cadences reaching a crescendo as the sun set, and then the slaughter was on, the men in white boots moving quickly down the line to slit the throats of the lambs, which fell to the ground, their blood flowing into the trench.

Now was the time of rejoicing, of handshaking and kissing and crying. The men smeared blood on the foreheads of their family members—even a pair of infants in a double stroller bore the mark of the lamb—and the sight of red on white was strangely affecting. Salwa appeared at my side to tell me that the blood on the forehead was what distinguished the sons of Israel from the sons of Egypt. “This is to remind us of our story,” she said, touching her brow. “

After a while, the men turned to preparing the lambs for the feast, slicing off their fleeces and hooves, removing their entrails and innards to burn on the grate placed over the end of the trench, salting the meat. Long, sharp sticks were propped against the metal rods, and it took three men to thread a lamb on a spit. Then one by one the families carried their lambs to one of the six fire pits, the tannurim from which the flames rose six feet or more.

Flames rise from the cook fire.

Sheep on spits stand propped against a building while the fire is readied.

Lamb spits are lowered into the pit for roasting.

The high priest and elders joined the women and children in a covered enclosure surrounded by wire mesh to sing more prayers. Outside, two of the Orthodox Jews whom I had met on top of Mount Gerizim were arguing with a pair of Samaritan elders over the meaning of the feast. “The Torah says this, the Torah says that,” was how a Samaritan boy translated their dispute for me, and just at the moment when the men beards and black hats seemed poised to strike the men in white all four began to laugh. More prayers were sung, and then all at once the men lowered eight lambs into each pit, spread blankets over them, and then sealed in the heat and smoke with mud—buckets of mud carried to each tannur. A plume of smoke would rise from a hole, and a man would fall to his knees to cover it with mud. The spits were sawed off to two feet high, the Israeli flag came down, the soldiers and tourists dispersed. The Passover site was left to the Samaritans, divided now into two groups, men burning the last of the debris over the fire, and in the cage older men, women, and children talking or playing.

* * *

Husney Kahen, the museum director, invited Maath and me to join him for a few minutes before we headed home, and so we followed him up the steps to a flat overlooking the Passover site. He asked Maath to switch on the light in the drawing room—Samaritans could not touch electrical devices until the next day—and then, throwing off his robe with a kind of violence, he slumped into a chair, exhausted. His wife bickered with him for a minute before bringing us pink lemonade and a single date apiece, and after he had drained his glass Kahen described the rest of ceremony: how quickly the Samaritans would eat the lamb at midnight; how they would pray until two, then rise again at five to pray for several more hours before resting until noon. At 83, he showed no sign of slowing down, despite being hospitalized earlier in the week after suffering what his daughter feared was a small stroke. He talked about his efforts to preserve the heritage of the Samaritans—his speeches at international conferences, his creation of the museum, his plans for a library. He wanted to digitize the unknown texts in the possession of the community; record prayers and hymns; publish the fruits of his forty-give years of research—books on the history of the Samaritans, Genesis, Exodus, Mount Gerizim. After careful study of some 7000 differences between the Hebrew and Samaritan versions of the Torah—letters and accents, words and an occasional phrase—he had discovered what he believed to be the route taken by the Israelites on their return from Egypt—a mystery that had eluded generations of scholars. Alas, the book remained unpublished, because he lacked the money to pay a printer.

Husney Kahen, director of the Samaritan museum. (Staff / Reuters / Corbis)

“What is my work?” he said, his voice rising. “It’s peace. We don’t want to throw the Israelis into the sea, but the Palestinians need a state. Whenever I speak to Israelis or Palestinians I say that war is why the Samaritans are now so small. Only war.”

Outside, the smoke was so thick that the street lamps were barely visible. Maath drove slowly through the smoke, on the dark road, afraid that he would make a wrong turn and end up in the settlement. But lights appeared near Har Brakha. We passed a settler and his son returning from the ceremony, and then we started down the mountain, toward Jerusalem.

[Note: This is part two of a series of web exclusives on the religious ceremonies of outsider communities. Part one was Elliott D. Woods’s story “Easter in Gaza.”]