The Flight of the Rohingya

Editor’s note: This is the first post in a two-part series on the Rohingya in Burma. For more about Burma, see our Summer 2012 issue, Burma Exhales.

Blind in one eye after being beaten in the head during forced labor, this man fled from Burma in the mid-1990s and is one of an estimated 300,000 undocumented Rohingya now living in the southern part of neighboring Bangladesh.

It was a rainy afternoon in southern Bangladesh in December 2010. Monzur and three other men were sitting on the dirt floor of Monzur’s hut. The structure was held up by thin bamboo sticks and made of dirty plastic sheets. Almost two years had passed since Monzur and others from his town had fled their small village in western Burma. In Bangladesh they are unrecognized as refugees and forced to scratch away a hand-to-mouth existence. But it is the nearest place where they can live with relative security and sleep at night free from the fear they’ve lived with for decades.

The Rohingya are a Muslim minority who have lived in the Rakhine State (historically known as Arakan) in Western Burma for generations. Today most Rohingya primarily live in the isolated townships of North Rakhine, which borders neighboring Bangladesh.

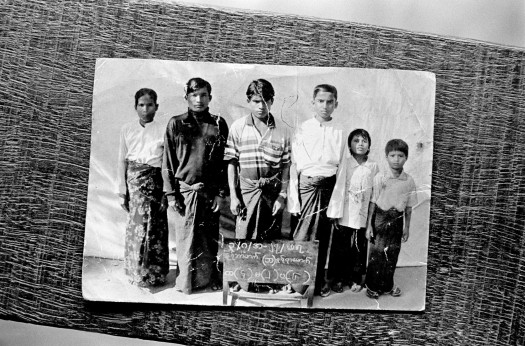

In Burma, authorities closely monitor Rohingya families. Most Rohingya are not permitted to travel beyond their village. Family household registers are updated regularly so the authorities know who and how many Rohingya are in each house. Any discrepancies to these records are punishable by fines and arrest. This is a photograph taken by Burmese authorities of a Rohingya family in Burma. The entire family eventually fled to Bangladesh in 2009.

Over the past 40 years, specifically since General Ne Win came to power in Burma in 1962, successive Burmese governments have claimed that the Rohingya are not from Burma, but are Bengalis who illegally migrated to Burma during British colonial times. While migration from the Indian-subcontinent was quite common prior to Burma’s independence in 1948, the Rohingya trace back their roots in Arakan for centuries. In the years between independence and the military coup of Ne Win, the Rohingya were considered and recognized by many of Burma’s political leaders (including Burma’s first and second Prime Ministers U Nu and U Ba Swe) as being a people and race belonging to the larger fabric Burma.

But this all changed after 1962. The Burmese authorities have done just about all they can to exclude the Rohingya community from belonging to Burma. Violent, large-scale crackdowns targeted toward the Rohingya—like Operation Naga Min or Operation Dragon King in 1978, and Operation Pyi Thaya or Operation Clean and Beautiful Nation in 1991—forced hundreds of thousands of Rohingya to flee Burma into Bangladesh. Further, in the 1982 Burma Citizenship Law, the Rohingya were not listed as one of the country’s 135 “national races” entitled to Burmese citizenship, effectively making some 800,000 Rohingya in Burma stateless—even after living for generations in Arakan.

These women were forced to stand in water up to their necks and were verbally and physically abused by NaSaKa. Eventually 120 families from their village fled to Bangladesh.

With the creation of the border security/military force Nay-Sat Kut-kwey Ye or NaSaKa in 1992—a force to be found only in North Rakhine, where they are the main perpetrators of human rights abuse against the Rohingya—the day-to-day lives of the Rohingya took a dramatic turn for the worse, and they have since been deprived of many fundamental rights. They face severe restrictions on the right to marry, are subjected to forced labor and arbitrary land seizure and forced displacement, endure excessive taxes and extortion, and are denied the right to travel freely. As reported by most Rohingya I’ve met, almost all aspects of their lives in North Rakhine are controlled or exploited by NaSaKa.

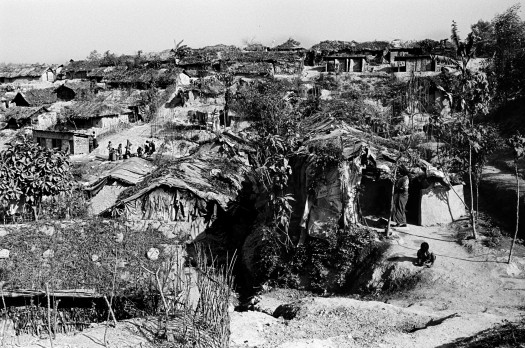

Undocumented Rohingya in Bangladesh gather together for protection and create makeshift refugee camps. In 2008, undocumented Rohingya began to create a new makeshift camp just south of Cox’s Bazar. The Kutupalong Makeshift Camp first started out as a dozen families. Now it has swelled to over 20,000 people. Aid workers say conditions in the camp are some of the worst they have ever seen.

Some 300,000 Rohingya, like Monzur, have left Burma and now live in southern Bangladesh, where they are exploited, unrecognized, denied almost all humanitarian assistance, and in recent years, have faced a growing intolerance toward them by their Bangladeshi hosts.

Monzur says, “Rohingya people who are living in Myanmar don’t have rights. Even a bird has rights. A bird can build a nest, give birth, bring food to their children and raise them until they are ready to fly. We don’t have basic rights like this.”

To read the second part in this series, click here.

Rohingya in Bangladesh have faced growing intolerance in Bangladesh. A Rohingya man stands in front of the office of the Anti-Rohingya Committee in Teknaf, Bangladesh. The Anti-Rohingya Committee see the Rohingya as a threat to Bangladesh interests and national identity and want to see all Rohingya in the area pushed back to Burma.

About the Author

Greg Constantine is an award-winning photojournalist from the U.S. currently based in Southeast Asia. For the past six years, he has worked on a project documenting the plight of the Rohingya from Burma. His second book, Exiled to Nowhere: Burma’s Rohingya, was just published. Also, a groundbreaking iBook, In Search of Home, exploring the issue of global statelessness—a collaboration between Constantine, writer Stephanie Hanes and the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting—was also released. Visit Exiled to Nowhere to find out more. Part of the reporting for work on the Rohingya was provided by a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.