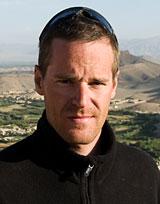

Cairo Journal: February 4

An anti-government protester shouts along to a chant on the approach to Tahrir Square, in the downtown area of Cairo, Egypt, where confrontations between supporters of President Hosni Mubarak and those calling for his resignation escalated to brutal violence. (Elliott D. Woods / Redux)

After an unsettling ride into town on Friday morning, February 4, I dropped off my bags at my hotel and headed to Tahrir Square for the afternoon. I hopped a cab from the north end of Zamalek to the Qasr El-Nil Bridge, which all of my friends told me would be the easiest entry point. The Sixth of October Bridge—the most obvious entry point to Tahrir Square—was a red zone on the map as far as I was concerned. Two days before, the bridge had been a flash point for violence between Mubarak’s thugs and anti-government protesters, who hid behind corrugated iron barricades and defended themselves with rocks and cobblestones dug up from the streets and sidewalks around Tahrir.

A pair of Egyptian tanks had the entrance to the Qasr El-Nil Bridge sealed off, and two long lines of protesters were working their way past soldiers performing ID checks and pat-downs. The mood at the bridge was relaxed, and no one seemed to notice the arrival of a foreigner toting a camera bag.

When I got to the front of the line, I showed my passport and opened my bag, and the soldier checking me shuttled me on through without so much as a question. By that point, the military’s senior command had already issued a statement saying that the Egyptian army would not use force to put down the protests. The protesters had made an early effort to embrace the army—with chants like “el-geish wa el-nass fi waheda,” or “the army and the people are one”—and it appeared successful. Were it not for the tanks, riot helmets and machine guns, the protesters bedecked in Egyptian flag-colored headbands and face paint would have seemed like hopped-up sports fans on their way into a home game.

When I reached the other side of the bridge, I saw a burned out truck and rows of concertina wire spread the street, guarded by a line of soldiers in riot gear. I crammed myself into a human funnel several hundred people thick, and the crowd slowly pushed me along through the last military ID check. It was in the roiling crowd that I heard protest chants for the first time, among them the signature “As-Shaab youreed asqaat el-nizam!” which means, “The people want to bring down the regime!”

As I elbowed my way to the checkpoint with the rest of the sweating, chanting mass, I also heard the first of many off-putting remarks that would continue throughout the following week. I had been chatting with two men squished behind me when I heard a woman’s voice say, “I recommend that you don’t speak Arabic.” The voice belonged to a young woman, unveiled, looking fashionable and only mildly flustered as her boyfriend or brother tried to keep her from getting crushed.

“Why?” I asked.

“It makes people suspicious to hear a foreigner speaking Arabic. People know there are a lot of Israelis who speak Arabic, and they might think you are Israeli.”

It wasn’t the first time I’d come across that idea. I was sorry to hear it again, though not surprised—Egyptian state media had been pumping the population full of bile about how foreign intervention was responsible for all of the protests, and about how foreign journalists were really undercover agents provocateurs. Mubarak’s state TV had so successfully scrambled the country’s brains over the decades that the very protesters calling for freedom from censorship, among other things, were unable to tune out the state’s lies more than a week into the revolution.

Mubarak was so desperate to control the messages coming into and out of Egypt in the second week of protests that he forced the country’s mobile and Internet service providers to shut down. The government also closed Al Jazeera’s Cairo bureau, arrested a slew of the channel’s employees, and launched a smear campaign to convince the Egyptian people that Al Jazeera was a propaganda mill bent on the destruction of the state. (A doorman in my neighborhood asked me if I’d heard that Al Jazeera said Omar Suleiman—Mubarak’s newly appointed VP and lifetime right-hand man—had died. “He’s not dead! He is alive! You see how Al Jazeera lies!”)

In a brilliant stroke, Al Jazeera responded to the government shutout by offering their stream for free to any satellite channel that wanted to run it. Instead of one channel showing live feeds from the square and giving face-time to angry protesters, there were fifty.

Mubarak’s attempts to cut off Egyptians from the world and from each other backfired. Rather than forcing them into the dark, Mubarak forced them into the street—the only place where they could satisfy their curiosity.

I passed through the final ID check and entered into a tunnel of clapping protesters who were chanting “Raise your head! You’re Egyptian!” And even though I am not Egyptian, the spirit was contagious. I’ve seen a handful of protests in my life, from Hamas parades through the streets of Gaza City to labor protests right here in Cairo, but nothing I had ever seen comes anywhere close the scale of Tahrir Square.

The name Tahrir Square is misleading in the sense that there’s really nothing square about it. There is a traffic circle at the center, and the perimeter is flanked by the salmon-hued Egyptian Museum, at the edge closest to the Nile River, and the Mugamma at the other end, a crescent-shaped concrete behemoth where Egyptians have to go to apply for just about everything, from passports to marriage certificates.

Egyptian protesters gathered in Cairo’s downtown Tahrir Square. (Elliott D. Woods / Redux)

On Friday, February 4, there were packs of protesters clustered from one end of Tahrir to the other. There was an air of festival, with several stages going on simultaneously; you could listen to a sheikh from Al Azhar delivering an uplifting sermon, or you could walk fifty meters and get into a passionate call and response with a leader of the Facebook revolution. Hundreds of people walked around with bandages on their heads and faces from the fighting two days prior, but there was to be no fighting that Friday—or on any subsequent days, for that matter. By February 4, with outside agitation having disappeared as quickly as it flared up, the revolution had become truly peaceful.

As journalists filmed and photographed, they were filmed and photographed in turn by dozens of mobile phone-wielding citizen journalists. There were rumors that the Egyptian secret police were paying people to film westerners in Tahrir, but I doubt it. Shooting your own cell-phone video from Tahrir was the 2011 equivalent of snagging a chunk of the Berlin Wall.

***

A composite sketch of an Egyptian taken from the thousands of faces at Tahrir Square would reveal a fascinating amalgamation: half sun-weathered, bearded, or shrouded in a full-face niqab; the other half fresh-faced, t-shirted, and sporting new Gucci sunglasses and a manicure. While the West panicked about how the Muslim Brotherhood would capitalize on the chaos, a broad swathe of Egyptian society was literally rubbing shoulders in Tahrir Square as peers for the first time in more than half a century.

A thirty-two-year-old psychologist named Fatima, the first streaks of white in her unveiled black hair, made a plea for Americans to look at Tahrir and see a picture of a diverse and united Egypt that defies stereotypes: “We want to work, we want freedom of expression, we want democracy. We’re Muslims and Christians, we all live together and we respect each other. We’re very misrepresented in the West, and our government is not a representation of who we are.” I asked Fatima to tell me her dream for a future Egypt without Mubarak. “I want to be able to walk in the streets and be proud that I am free. I don’t want to have to worry about the police harassing me. I want to be able to vote, I want to understand my government, and I want to be part of the decision-making.”

Fatima, thirty-two, an Egyptian psychologist, at Tahrir Square on Friday, February 4. (Elliott D. Woods for VQR)

A crowd gathered around the spot where I was talking to Fatima, and everyone wanted their chance to say something to the camera. A hefty, dark-skinned Koran teacher named Allah Mohammad, forty years-old, with a henna-dyed beard and a prominent zebiba—the forehead stain that results from pressing one’s head to the ground two hundred times a day in prayer—told me that he had been imprisoned for twelve years without explanation. It’s a common story in Egypt: kids as young as nine or ten snatched up from the mosque and locked up in secret jails where they are interrogated and tortured for years, never to go to trial, sometimes never to emerge. But Allah Mohammad made it a point that he did not come to Tahrir for religious reasons, or even to protest his imprisonment. He said he was protesting because hundreds of thousands of Egyptians were starving, unemployed, and desperate, and he blamed Mubarak’s regime.

Bread has been a metaphorical rally point for revolutions all over the world—it was a sharp rise in bread prices in 1789 that fired the indignation of French peasants for whom intellectual rhetoric held little sway—and Egypt is no different. In Egyptian Arabic, the word for bread is “aish,” which is also a word for “life.” To keep the people satiated, the government has subsidized state bakeries to keep the price of bread at about one penny per pita-like loaf. So while double-digit inflation has ripped through the economy in recent years and doubled the prices for commodities like meat and sugar, the government could at least claim to have kept the cost of “life” down; however, as one would expect in a country defined by systemic corruption, there is more to the story.

Government dispensaries produce a limited supply of bread each day, and corrupt bakers sell bread in bulk to restaurant owners and street sellers who resell the bread at double the price. Often people wait in bread lines hundreds of people deep only to get to the window and find out the day’s supply has run out. And so bread became an obvious anchor in the revolutionary refrain, “Aish, shoghl, wa horriya.” Bread, work, and freedom.

An Egyptian protester weeps as he prays in Tahrir Square. (Elliott D. Woods / Redux)

Whatever fears I had when I set out for Tahrir were allayed immediately by the warm reception I found among protesters of all ages and backgrounds in the square. At one point, I climbed atop an iron railing to photograph the surging crowds, and as I stood there I felt a hand tapping my ankle. I looked down to see a smiling man wearing the trademark red felt cap of an Al Azhar sheikh—in his outstretched hand he held a date-filled cookie called a maamoul. A few minutes later, I felt his hand again, and this time he was passing me a mango juicebox. Back in the crowd, dozens of voices wafted by saying things like “thank you for supporting us,” or, “thank you for spreading our message.”

I wish I could say that my reception among the crowds was fully positive, but there had been too much violence and too much tension for everyone in Tahrir to offer a warm welcome. In one instance, I was rebuked by a group of young women who approached as I was filming an interview with a man who had just finished praying.

“What are you doing here?” one of the young women shouted, scowling and pointing a finger in my face.

“I’m a journalist,” I replied.

“What is your nationality?”

“American.”

“Why are you really here?” she shrieked, seething, her voice shaking with anger. “How do we know you’re really a journalist?”

Her invective grew, and eventually a crowd closed in on me. Voices rose all around me; some called for her to back off, others yelled for me to show my passport and prove that I was an American and a journalist.

“Foreign countries have interfered in Egypt’s affairs for too long,” she yelled, “and now we are not asking for anyone’s help. We do not need you here. We do not want you here. We respectfully ask you to please leave the square.”

I respectfully turned and ducked out of the mob, knowing there was no point in arguing, but I didn’t tuck tail and leave the square. Nor did I believe that the majority of the tens of thousands of Egyptians gathered in Tahrir would support her request. Still, I could easily see her point. I had seen a poster that day with Mubarak’s presidential portraits chronologically aligned with every president from Reagan onward, and I knew as well as anyone else that three decades of Mubarak’s dictatorship would not have been possible without political and financial support from the United States—at an annual cost of about $1.5 billion taxpayer dollars in recent years. Even Obama studiously avoided the ejection button until the end. In pursuit of American objectives in the Middle East—namely the easy access to energy resources and the protection of Israel—we have invested in dictators who happily repress unpleasant elements in their own countries (democratic activists as much as Islamists) and promise not to raise a fuss over Israel’s atrocious human rights violations. After all, wouldn’t that be a case of the pot calling the kettle black? Our dictator-dependent strategy is well-known to people in this part of the world—and it does much more than provoke anger. It provokes a powerful feeling of betrayal.

How, on the one hand, can we claim to fight for democracy in places like Iraq and Afghanistan—at a cost of thousands of American lives and tens of thousands of Iraqi and Afghan lives—and then turn our backs on places like Egypt, where peaceful activists have been struggling for democratic rights for decades?

I strolled away from the crowd that had enveloped me, leaving my antagonist and her friends arguing with a group of my defenders. Several young men trailed behind me, trying to reassure me. “Don’t worry,” they said. “Everything is okay.” Within minutes I had another group of protesters surrounding me, eager to record their statements to the world. Some spoke in English, one spoke in French, and many spoke in Arabic. I filmed a half-dozen of them, and whether they were bearded or dressed in jeans and sneakers, they all said more or less the same things: “We want our dignity. We want to be free.”