Cairo Journal: February 3

[Since last week, VQR has had reporters on the ground in Cairo. Beginning today, the blog will feature their words and photographs, after a sufficient passage of time to allow them to move to new locations.—Ed.]

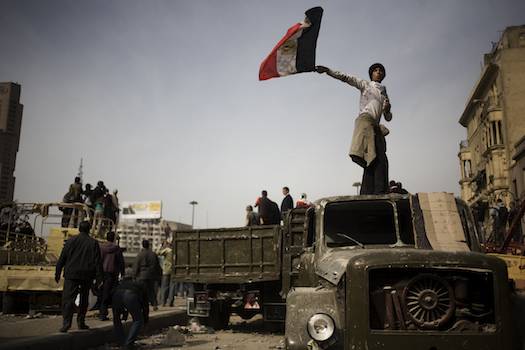

Anti-Mubarak supporters rally other supporters for stone throwing against pro-Mubarak supporters on the road from Tahrir Square. (Nadia Shira Cohen for VQR)

I decided to cross the Nile by way of the bridge nearest my hotel—and found myself among pro-Mubarak protesters and a phalanx of military tanks.

I had arrived in Cairo barely forty-eight hours before, under the thin alibi that I was a painter, that I painted from photographs and that is why I needed all the camera equipment. As I approached immigration, I fretted, wishing I had a better story. But the man behind the window in the box took a look at my passport and smiled. “Nadia,” he said. “Where is your father from?” I gave a questioning look and he explained that my name was Arabic. Then he stamped the little blue book and waved me through to baggage claim. We departed from the nondescript terminal and sardined into a sedan, the interpreter’s cheap perfume wafting up from the backseat. We passed street after street of citizen checkpoints, guarded by men with sticks and secondhand Kalashnikovs. Traffic was heavy and dotted by tanks, but we arrived at the hotel without incident.

Now, as I crossed the bridge, I was greeted by a wave of pro-Mubarak supporters, and when they saw my camera they were not as understanding as the airport immigration agent had been. They shook their fingers in protest. Some waved their shiny color-copied photos of Mubarak. One man started shouting at me through his tobacco stained teeth and when I continued he shoved the camera back in my face and told me to get out of there. Another man asked where I was from and when I told him America, he asked me what I was doing there.

At that moment, a couple of friendly men began talking calmly to me and guiding me through the crowd. One of these young men, named Slem, watched over me while I clicked the shutter. He advised me when it was safe to move and where. I followed. We moved slowly to the end of the street where four heavily armed tanks barricaded the entrance. An angry man waved a stick embedded with nails in my face, demanding I stop taking pictures immediately. Slem calmed him down and I slipped my camera back in the bag.

I crossed the barrier heading towards Tahrir Square where all the protesters chanted against President Mubarak. But the man with the stick recognized me—and now he had friends, all with sticks of their own. They cornered me on the ramp to the bridge against the railing, and I was quickly surrounded on all sides. Slem grabbed my arm and yanked me out of the crowd. I ran as fast as I could to the tanks and pleaded with a soldier to let me inside. He took me by the collar, opened the door to the back of the tank and dropped me inside.

An Egyptian soldier runs through Pro-Mubarak supporters to his tank. (Nadia Shira Cohen for VQR)

I looked around in the dark. Two soldiers sat across from me in the shadows concealing their faces; another bathed in the sunlight coming from the open top hatch. It was hot inside and smelled like stale Marlboros. The blondish good-looking soldier asked me, in perfect English, what had happened. Words cascaded out of my mouth. I hadn’t realized just how shaken I was until I tried to put the experience into words.

“What is your name?” the soldiers asked, trying to settle me.

“Nadia,” I replied.

He smiled—just as the immigration agent had, just as almost every single person I’d met in Cairo had. Nadia was an Egyptian name, he said.

“Have you heard of DJ Nadia?” he asked.

I shook my head. “What kind of music does she spin?”

“50 Cent,” he said, and we smiled together.

I asked what the plan was. He pulled his flak jacket over his shoulder and loaded a round of ammunition into his gun. Then we walked out of the tank together, and Slem was waiting for me with what almost seemed like tears in his eyes. He took my arm in his immediately and held it very tight as we walked under the protection of the soldier. I was touched by the affection of these utter strangers.

It’s true that, as journalists, people like me are risking a lot: being thrown into jail, being beaten up, having our equipment taken—but the consequences for us pale in comparison to the chances routinely taken by average Egyptians who act to protect foreign journalists. We can always be evacuated; even if we’re detained, we have the might of the American government to lobby for our release. Yet many fixers and drivers and anonymous protectors who emerge from the crowd are being detained without word of the term of their incarceration, without any way to petition their government. I’m beginning to see some of what this revolution is about.

Asmaa and other anti-Mubarak protesters in Tahrir Square gesticulate at a government helicopter circling overhead. (Nadia Shira Cohen for VQR)

A woman seeks medical treatment in a makeshift hospital in Tahrir Square. The woman had tried to protect a pro-Mubarak supporter who was being beat up by anti-Mubarak activists. She lied and told the agressors that she was his mother in order to save his life. (Nadia Shira Cohen for VQR)