The Blue People, or Alternatives to the Modern State and Other Desert Mirages

Tangled within the problem of creeping Islamic militancy across the vast Sahara, and into the countries of the Sahel that fringe its southern edge, is a conflict at once more abstract, less tractable, and as old as politics itself: a rift between the people who submit to a centralizing authority and those who would flee it.

Since January 11, French forces have spearheaded a ground and air intervention into the West African country of Mali to restore its “territorial integrity,” in the words of President François Hollande, or rather to wrest back control from Islamic insurgents who began imposing a harsh, literal interpretation of Sharia law since taking over an area as vast as Texas in Mali’s arid north last April.

In a country that prides itself on being the cultural heir to ancient empires, long touted as a model of relative political stability and democracy in West Africa (at least until a coup last March), the Islamic insurgents chopped hands off thieves, demolished bars, and stoned adulterers. They also banned music. As a PR move, that was perhaps their worst miscalculation. Dragging guitars and drums out of houses, they set the instruments ablaze and threatened to cut off the fingers of anyone who dared to play them. Malians were horrified. “Culture is our petrol,” Toumani Diabete, the globally celebrated kora player, told a reporter from The Guardian newspaper. “Music is our mineral wealth. There isn’t a single major music prize in the world today that hasn’t been won by a Malian artist.”

On January 8, about 600 Islamic insurgents in about 150 vehicles appeared to be advancing on Mopti, a bustling port city, and Bamako, the capital of Mali, about 400 miles further south. The offensive unleashed immediate French action after weeks of deliberate preparation, which had included a UN Security Council mandate for a regional African force.

The dominant Islamic insurgent group that took over the area last year calls itself Ansar Dine, the Defenders of the Faith. Its avowed agenda apparently began and ended with localized Sharia rule. But the area also became a haven for transnational jihadists, including members of Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, or AQIM, an avowed affiliate of Osama Bin Laden’s core Middle Eastern group that had first appeared in other parts of North Africa in 2003. As the eyes of the West focused firmly on the Middle East, AQIM quietly spent the past decade raking in tens of millions of dollars from governments such as Germany and France as ransom for a steady trickle of Western hostages. Other transnational jihadists include the Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa, or MUJAO. However pristine members’ dreams of a continent-wide caliphate, the groups reportedly forged ties with drugs traffickers and arms smugglers. Ungoverned spaces have a way of attracting the dregs of civilization.

And therein lies the rub for the separatist—if decidedly secular—rebels who accidentally paved the way for the Islamist takeover of northern Mali in the first place. As it happened, the Islamic takeover in northern Mali hinged in large part on the unresolved disaffection of Mali’s minority Taureg people, the “blue people,” semi-nomadic pastoralists who have for centuries crisscrossed the Sahara, plying ancient caravan routes that bridge the great divide between the Arab-infused Mediterranean culture of the Maghreb and the vast African continent beyond.

The modern state has never had much use for outliers, for the recalcitrance of the wild hinterland and the people who flee there for the sake of autonomy. So theorizes James C. Scott in The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia, an anthropological inquiry of roughly 100 million inhabitants of an entirely other unforgiving region of the world: the mountainous zone between China, India, Burma, Laos, and Thailand. Scott concludes those millions fled over the course of centuries as a deliberate ploy to avoid shackles of statehood such as taxes, indentured servitude, even slavery. In the process, they developed ways of life, languages, and identities that have ever since kept them remote.

In a world ruled by the assumption that states are the best units of societal organization—in which every rock has been planted with a national flag—Scott’s work shines a carnival mirror, a distorting lens that offers a compelling justification for the persistence and entrenchment of “tribal” or “minority” peoples as a matter of self-protection. To vulgarize his argument: states bad, local governance (anarchy?) good. (So much for progress, civilization, and all that).

But “ungoverned spaces” have, at least since 9/11, more often had a bad name. In national security circles they are a source of increasing anxiety, be they Pakistani Waziristan, rife with violent sectarian or clan-based governance; Mexico, lately overrun with criminal cartels; or virtual realms such as the Internet or global finance, subject to fraud and cyber-hackers.

For all the growing acceptance of every individual’s sovereignty, the world today remains unforgiving of the stateless or the state-defying (see ongoing disaffection from the Kurds to the Kachin). Conventional wisdom takes for granted a nation’s right to re-impose its sanction over its own territory—unless or until that imposition involves an evident attack on innocent civilians. But even then, what can you do, short of conscripting a national army, or an alliance of such? (Naming and shaming! Security Council resolutions! Sanctions!)

Across Africa, the mismatch between political borders and peoples during the withdrawal of European powers was so potentially widespread that most countries agreed to an ironclad policy of adhering to the old colonial frontiers. Which never entirely alleviated the predicament of those who fell outside the easy confines of statehood. Desert, a novel by the Franco-Mauritanian Nobel laureate J M G Le Clézio, confronts that tension head on. He juxtaposes the grueling escape of the Taureg across the Sahara in 1909 ahead of advancing French colonial forces with the palpable sense of deracination of their descendents as they grow up in exile in the modern slums of Tangiers and Marseille.

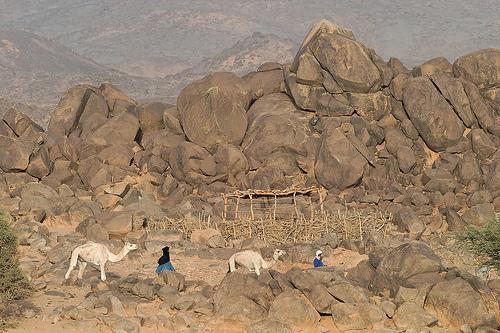

Le Clézio captures their desert odyssey with a dreamlike lyricism, punctuated by a constant repetition of images, as if time is circular and different physical laws apply to them. In their wispy veils and turbans, they beat back the relentless winds and sands, the extremes of temperature, advancing beyond hunger, beyond thirst, “to the other end of solitude, towards night.” For guidance, they look up to the stars, “a country outside time, outside the history of mankind.” The Taureg supposedly see many deserts in the Sahara. Their world is, or was, transnational, muddying up the neat categories of Maghreb and sub-Sahara, east and west. Borders, in that mindset, are as evanescent as footprints in the shifting dunes.

Defeated by the central government in successive rebellions since 1960, the Taureg of Mali retreated to areas of the country that suffered severe droughts in the 1970s and 1980s. The combined hardships of life pushed many into neighboring Libya and Algeria. Last January, an estimated 1,000 Taureg rebels calling themselves the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad, or MNLA, stormed towns in Mali’s northern desert, emboldened by fighting on behalf of Colonel Muammer Qaddafi and a surge of heavy weapons that they had seized from his massive arsenal. They quickly overwhelmed the ramshackle, and thinly equipped, Malian forces and by March had declared an independent state in northern Mali that they called Azawad.

The MNLA initially found common cause with the Salafist Ansar Dine, whose founding leader is a Taureg who also fought alongside Qaddafi in Libya. But when the two groups fell out over the imposition of Sharia law, Ansar Dine eventually gained the upper hand.

In a Franco-German documentary filmed several months ago, members of the MNLA and affiliated Taureg villagers squat on the cracked soil of northern Mali or rumble in pickups across an arid, rock-strewn landscape punctuated by arthritic trees, recounting the neglect of the central government: no schools, no health centers, no water pumps. No roads. Slowing his SUV beside a mass of shallow mud pits crowned in rocks that barely emerge to the naked eye from the seamless expanse of red dust, an MNLA activist in a green turban said they were the graves of relatives and friends who were killed in successive Malian attacks on Taureg civilians in decades past.

Another swept his eye across the horizon toward Algeria, and told of the MNLA’s disaffection as they watched AQIM take over caves or former colonial fortresses that had served as their launch pads for rebellions. The idea of it sullied their own history, he said.

In the trade-off between backing the Islamic insurgents or the state, the Taureg have since made their choice. Spokesmen for the MNLA say now they are prepared to fight alongside the French and Malian army to expel AQIM and MUJAO.

As the cities of Gao, Kidal, and ancient Timbuktu fell in recent days to the steady French-led advance, Malians poured into the streets in bright clothes, danced and played music.

The insurgents appeared to have melted away into the desert, raising the specter of a long, drawn out conflict. I wonder if vanishing into the sandstorms alongside them are the political dreams of rebel Taureg?