The Informant

Not long after Stewart vowed to delete Grindr and Jack’d and every other dating app he’d ever downloaded, Anders Nyberg emailed to say he’d moved back to Maine and would be coming down to New York for three days. In college, Stewart had fantasized about Anders endlessly—the lanky kid with black hair and moss-colored eyes from a hamlet twenty miles south of the Canadian border. Anders was on the soccer team, and in the winter he spent his weekends cross-country skiing and making furniture out of reclaimed timber from an old Vermont barn. He had a tattoo of the Algerian flag on his left shoulder and lived off campus in an apartment with a woman from San Francisco and a Nigerian guy whose parents owned a yacht. He took women’s studies classes and wrote papers about post-structural feminism, and, even though he dated women, he never seemed completely straight.

After graduation, Anders traveled to Algeria and Morocco and Portugal, where he lived on a sailboat with a woman named Louna and wrote Stewart long letters about the books he was reading and what he called his “spiritual journey.” Each letter filled Stewart with a maelstrom of emotions. Then, eventually, after Anders sent him a birthday card with news of a new girlfriend, a woman from Morocco whom Anders described as the love of his life, Stewart decided that hoping he’d ever reciprocate his feelings was a lost cause. He told himself to move on. The last he’d heard, Anders was living in a small fishing village north of Lisbon, making pottery.

They agreed to meet at a vegan place in the East Village at 7:00 p.m. Despite the fact that Stewart was usually quite punctual, he found himself running a few minutes late. Just as he was leaving his apartment, he got drawn into a long conversation with his building’s super, who’d been promising to fix a leak in the kitchen. Unable to find a cab, Stewart sprinted from Ninth Avenue to Broadway, where he turned right and headed downtown. Two blocks north of Union Square, he dashed across the street without seeing an oncoming taxi. The cab plowed into him at a velocity of thirty-seven miles per hour, sending him flying.

It’s often said that when you die your life flashes before your eyes. But in the moments before he lost consciousness, the only thing Stewart registered was the intense flash of pain on the left side of his body—his hip and his femur, which had been shattered in thirteen places—and then, for just a moment, the preternatural feeling of being borne into the air as if he were a child again and his mother was holding his tiny hands in her own, spinning him around and around (his body almost parallel to the ground as he screamed with delight).

The next thing he knew, he was standing in line in a bleak cement plaza, the sky above him heavy with lead-gray clouds. To his right stood a squat rectangular structure whose concrete façade was cracked and weathered. In front of him, he saw a few dozen people in line. He couldn’t figure out where he was. Had he died and gone to Heaven? Instead of celestial, this place looked more like something Soviet, pre-Perestroika: large blocks of Brutalist buildings, one after another, metal benches attached seamlessly to the ground, shorn fields stretching into the distance.

The person behind him—a stocky woman wearing a turquoise wool coat and a magenta scarf—kept telling him to stop looking so disturbed. “It’s not that bad,” she chided. “It could have been much worse. My friend Marit Grünweiss ended up in F-19. F-19 makes this place look like the Ritz-Carlton Key Biscayne.” Stewart looked at the woman, perplexed. He had no idea what she meant by F-19. He assumed it referred to some region or district or precinct, but that made no sense, because why would Heaven have precincts?

“I know, I know—you were expecting gilded harps and halos and fluffy clouds,” she continued. “You’ll get used to it though. At least we have running water. In F-19, they have to use outhouses. They get their water from a well!” The woman introduced herself as Margaret and told him she was from Cincinnati. “Born and raised. That’s where I’m buried. I bought the plot with my husband. We prepaid so our kids wouldn’t have to worry about where to put us when we kicked the bucket.” She gave Stewart a little smile, and for a moment he wondered whether she was playing some kind of practical joke. “Plus, we wanted to make sure we were close to my parents. We didn’t want my sister-in-law getting involved. If we’d left it up to her, I probably would have gotten cremated. She’s a cheapskate.”

The woman—Margaret—paused and adjusted the scarf wrapped around her head. “Her whole family’s cheap,” she continued. “They wouldn’t even pay for their own daughter’s wedding. Ron and I had to pay for the whole thing. Thirteen thousand dollars. And that was back in ’89. You know what I could have done with that money? I could have gone to Mazatlán or Puerta Vallarta. Instead, I’m sitting at home, playing mahjong and watching The Price is Right.”

Stewart noticed the sky growing darker. He wished he had his fleece cap, because it was cold enough here that he could see his breath. He found it unsettling that everyone around him was acting so nonchalant, that no one seemed distraught or confused.

He smiled at Margaret, though he wasn’t listening to what she was saying anymore. He was wondering whether he was hallucinating, whether someone had slipped something into the salad he’d had for lunch. He was trying to piece things together, to figure out what had happened to him. Strangely, he wasn’t in pain. He kept checking his body, but he didn’t feel like he had any broken bones or lacerations or trauma to his face or his skull.

When he finally reached the front of the line—in the blink of an eye, it seemed—a thin man with wire-rimmed glasses handed him a rectangular piece of manila cardstock with the following written in black felt-tip pen: “Stewart Flecker. Precinct C-12.” The card was laminated and had an embossed seal as well as a small orange circle in the upper left corner.

“Don’t lose it,” the man said. “Keep it in your pocket at all times, even when you go to the toilet. Josef will take you to your room. He can answer any questions you might have.”

Stewart glanced at the man, whose clothes were too large, then at Josef, neither of whom looked elderly. Just then, a gray-haired woman with a cane and a sack of what appeared to be red onions strode up to Josef and asked him a question in a language Stewart didn’t recognize. She seemed quite upset and Josef said something sharp to her, in her own tongue, and she backed away, as if stricken. Josef took Stewart by the arm and guided him down a gravel path toward a large building with small windows that he said would be Stewart’s new home. The building was eight stories tall, and its exterior was spalling and streaked with rust-colored stains.

“Someone already explain the schedule?” the man asked as they crossed a plaza patched with snow.

“What schedule?”

“What time to get up. What time we meet for group exercise. What time meals are served.” Josef had at least three days of stubble on his face—mostly gray with flecks of black, and though he wasn’t particularly handsome, he wasn’t bad looking. Stewart realized then what had been bothering him: He hadn’t seen any gay people around. Not a single homo. He found it strange to suddenly be in a place where no one looked like they’d ever set foot in Balenciaga or Paul Stuart or even H&M.

He considered asking Josef how long he’d have to stay here and whether this was some kind of transitional space he was meant to occupy while the people in charge got his actual accommodations in order. He wanted to ask whether his permanent domicile would be less austere, somewhere more temperate, because he had no interest in spending the next umpteen years in such a dreary place. Stewart was only forty-five but his plan had been to retire in California, where he grew up and where his mother had lived until her death. He’s intended to buy a small condo with a balcony overlooking the Pacific. He’d hoped to use his retirement savings to do some travel. At home, in his walk-up in Chelsea, he’d kept lists of places he wanted to visit: Japan and Cyprus and the Azores; Alaska, Kenya, and Morocco. Above all, he’d always wanted to see La Recoleta Cemetery in Buenos Aires, where Eva Perón and Silvina Ocampo were buried.

Soon enough, he and Josef were standing in a dimly lit lobby, waiting for the elevator, and Josef was telling him dinners on Sunday were at 5:00, instead of 6:00, because lunch wasn’t served on the Sabbath. “If you’re smart, you’ll take an extra banana or orange at breakfast so you have something to snack on. That’s what I always do.”

Stewart was still having a hard time making sense of everything: just like that, he’d gone from the pulsing heart of Manhattan to some kind of Chernobyl trapped in time. He looked at the floor—studying the pattern of black and white squares—and it occurred to him the black of the tiles matched Josef’s leather boots. Both shades were dull, not like the absolute black of obsidian, but like the black you might see if you happened to come across a body of water, a lake, say, at night in the middle of winter: the kind of darkness that had a bit of luminosity to it, from the moon or the stars.

Stewart felt a tightening in his throat, and he wondered whether he might start to cry. He’d always been bad with transitions. Even moving twelve blocks south, from one rent-stabilized apartment to another, had been difficult for him.

“You’ve probably got questions,” the man continued. “But don’t worry: It’s not as bad as it looks. Heaven used to be nicer, but between the budget cuts and the mismanagement, this is what we’re left with. It may not be Arcadia, but it’s not horrible. And if you’re wondering what hell is like, don’t waste your time—that place is like Abu Ghraib.” Stewart was surprised by the comparison. He wondered how Josef knew about Abu Ghraib and how long he’d been dead.

As if reading Stewart’s mind, Josef continued, “Don’t look so confused. Just because we’re deceased doesn’t mean we don’t know what’s going on down there.” They were in the elevator now, making their way up to the sixth floor. The cab’s movement felt tentative, and he wondered whether they might get stuck between floors. Stewart heard a grating sound above him. The cab slowed, then lurched to a halt, and the door opened onto a high-ceilinged hallway. He was struck by how much it reminded him of his high school: gray, cavernous, dull linoleum floors.

The hallway was quiet, and as they exited the elevator and walked side by side, Stewart saw no signs of life. A moment later, Josef pointed to a splintered wooden door. “Here’s your room, my friend. Just across from the bathroom. Easy access,” he said, smiling. “Now make yourself at home. There’s a bar of soap for you and a towel. Just holler if you need anything.”

And, like that, Josef turned and walked back down the hallway, leaving Stewart to wonder whether he should call after him, because he still had questions. He wanted to know, for example, how Josef knew what was happening on Earth. Could people here, wherever he was, see what was happening on Earth? The idea took hold of him, for he was certain that being able to see what was happening in New York would make him feel less lonely and unmoored.

Stewart wanted to know whether it might be possible to see Anders, or at least get him a message, even just a text. He would have apologized for missing their dinner, would have told him he wasn’t angry that Anders had been out of touch for so long. He would have admitted that he loved him, that he’d loved him since college. He might even have admitted that he’d trolled the Facebook pages of college friends for any shred of news about him.

Stewart’s rational self knew there was no point, now that he was dead, in reminiscing about Anders or any of the other guys he’d fallen in love with over the years. On the other hand, he considered the fact that on more than one occasion his mother, Heike, had returned to Earth to visit him from the afterlife. At first, her appearance had freaked him out, but eventually he grew used to it, though her comings and goings could never be predicted.

During the first days after her funeral, he’d been happy when Heike visited him. Initially when she appeared, Stewart was still in Ventana Beach, cleaning out her condo, and he was incredulous—full of astonishment and delight. Astonished not just that his mother had somehow managed to come back from the dead, but also that he felt a tenderness in her presence he hadn’t felt in years.

His room was small and dank and smelled as if someone had let wet laundry pile up for weeks. The walls were cinderblock, the furnishings sparse: two single beds, both neatly made, a compact desk with a wooden chair, a narrow closet with five or six hangers and an avocado-green carpet. The carpet seemed entirely out of place—it was more of a shag rug than a carpet—and it looked quite fashionable. Next to the desk was the blue suitcase he’d kept in his closet on Earth. Seeing the suitcase filled him with sadness and yearning, because, somehow, it made everything feel more real.

Outside, the sky was darkening and only the faintest bit of light was filtering into the room through the window overlooking the courtyard, its concrete expanse riddled with pockmarks and cracks. Stewart put the suitcase on the bed closest to the window and unzipped it, deciding he should unpack his things and get settled before night descended. It didn’t look like he had a roommate—at least not yet—and he figured it would be prudent to claim a few of the drawers.

He tried to remember what his mother had told him about Heaven the last time she’d visited him. He had just stepped out of the shower and was rushing to get ready for a dentist appointment. He was drying himself when he heard her calling his name through the bathroom door.

“Stewart? I have to talk to you,” she shouted.

“I can’t now!” he hollered back. “I’m running late. Can you stop by later?”

“I can’t come by later. You know how they are! I don’t just snap my fingers asking to be excused.”

“Well, I’m naked. You can’t just show up whenever and expect me to be available!”

He dried his hair quickly, put on a shirt, wrapped the towel around his waist, and opened the door. He expected to see her there, waiting for him impatiently, but she was gone. He called out, apologizing for being short with her. He said she could come with him to pick up his new mouth guard if she didn’t mind taking the subway, but she was nowhere to be found. His apartment was empty.

During the first days after her funeral, he’d been happy when Heike visited him. Initially when she appeared, Stewart was still in Ventana Beach, cleaning out her condo, and he was incredulous—full of astonishment and delight. Astonished not just that his mother had somehow managed to come back from the dead, but also that he felt a tenderness in her presence he hadn’t felt in years. She visited six times in all, and, soon enough, she became as pushy and domineering as she’d been before her aneurysm.

The suitcase with Stewart’s things looked like it had been packed in a hurry. Normally when he went on a trip he folded his shirts and pants, but his clothes were scrunched up. Clearly the person who’d put his things into the suitcase knew nothing about him. They’d chosen his worst underwear, leaving his bulge-enhancing boxer briefs behind and selecting his frayed Hanes which were all too tight and, in some cases, stained. In terms of toiletries, they’d included the toothbrush that was worst for his gums, the free dental floss he got from the dentist, and an ancient tube of Crest, instead of his organic antiplaque toothpaste formulated with xylitol and myrrh.

He decided he should be grateful he’d been given any clothing at all, but he wished he’d been allowed to select the items he could bring along. He would have packed the selected poems of Seamus Heaney and Elizabeth Bishop and his stack of postcards from the Guggenheim and MoMA—featuring paintings of Miró and Chagall and Kandinsky—along with some Scotch Tape, so he could affix something uplifting on his walls. He would have brought the box of letters he kept next to his bed—letters he’d received from his mother over the years, and from Anders when he was in the Peace Corps—and maybe a container of lube.

Four nights later, the sound of knocking at his door roused Stewart from a dream in which he and Anders were in a rowboat, crossing an enormous lake. Again he heard the rapping, this time more insistent. He got up, put on his glasses, and made his way to the door, opening it slowly. In the crack of light, he saw his mother standing there in the hallway, wearing a heavy black coat and holding a large canvas bag.

“My god,” she said, pushing the door open and coming in. “It’s you! My son.”

“Mom?”

“You don’t know what I went through to make it here. I had to bribe a farmer to take me here in his truck, but then his engine broke down and I had to walk you never imagine how far. I thought the guards might catch me, but I made it. Luckily I still had my old key so I could let myself into the lobby.”

“How did you know I was here?” he asked, turning on the flashlight Josef had lent him.

“No—no lights! Are you crazy?”

“How did you find me? Are you okay?” Her face was caked with dirt; she smelled like she hadn’t bathed in weeks.

“Be quiet!” she snapped. “We have to keep our voices down so no one can hear us.”

“What the hell is even going on?” he said in a frantic half whisper. “Where are we?”

“I didn’t think I’d ever see you again,” she said, embracing him tightly, her odor filling his lungs. “I thought that was it.”

He began to cry, and she took his face in her hands. “There’s no time for tears. You have to pull yourself together. We don’t have the luxury of tears—you have to gather your things and we have to leave.”

“Leave? What do you mean?”

“We need to catch a train. There’s a train that travels along the perimeter of C-14 and comes through at 5:20 a.m. We must walk there to catch it.” In the darkness, her face looked haggard, her eyes as large and luminous as a leopard’s. “I can explain everything on the way. We have to walk through the woods to get there in time. Now tell me, do you have a bandage I can use?” She sat down on the edge of his bed and started to take off her boots. “I got a terrible blister on my left heel. The shoes they gave me are too small.”

“What kind of train is it?”

“What do you mean what kind of train is it? It’s a train! A train like any other train! It can take us to the countryside, there’s a cabin there where we can live. It’ll be safe. Now please, find me a Band-Aid or something I can put on my heel.”

He stood there looking at her, at the wrinkles in her face and her unkempt hair and filthy hands, and at her heel, because she’d taken off her left boot and her sock. He could see her foot in the patch of moonlight coming in through the window. Her toenails were terrifying: thick and yellow and claw-like. He watched her caress the inflamed area near the blister. He told her he didn’t have a bandage; all he had were his clothes and the things that had been in the room when he arrived.

“Then some toilet paper from the bathroom or a napkin I can put over this,” she said. “And I need thicker socks. My socks are too thin. I need something to cushion my skin.”

He went to his drawer and found a pair of black athletic socks. “Perfect. That’s good. I’ll wear those on top.”

“What train are we catching? Where does it go?”

“It goes north. They carry chickens and cows north for the spring, and we can get on with some of the farmers who travel that way. I got you an ID card already. Your name is now Amos Pierce. You have to remember that.”

The next thing he knew she was standing up, and opening the door, and striding down the hall toward the stairway. From behind, she didn’t look familiar. On Earth, she’d always worn bright-colored clothing—tangerine dresses and pink bikinis and citrine hats, but her coat here looked like it belonged to a Russian peasant. She could have been anyone, could have been a stranger taking him to be shot.

Outside, the sky was clear, the moon bright. Stewart saw his breath each time he exhaled. Heike was two strides ahead of him, walking faster than he’d ever seen her move. When they reached the gravel road outside the perimeter of the buildings she told him to hurry up, and soon enough she veered off into the woods.

“Why are you walking so slowly?” she scolded. “Look at me. I’m an old woman with a painful foot and I can move faster than you. We need to hurry. If we miss the train, that’s it.”

He asked what she meant, but she didn’t answer. It made no sense to him that people here still measured time with watches and clocks.

They scampered over branches and pine needles and patches of snow, Stewart carrying his blue suitcase in his right hand until he was sweating and his arm was sore. When he asked to stop for a moment to catch his breath, she refused, unleashing yet another diatribe.

They kept moving, and he wondered whether he should have stayed in his warm bed. Everything had happened so quickly and his mother hadn’t given him a chance to collect his thoughts. He asked her where they’d end up and whether it would be safe.

“Safe, yes, but not fancy. It has a well in the back and, if we’re lucky, some potatoes. People complain the land there is barren, but the soil isn’t as bad as you think.” In the distance, he heard what sounded like an owl as Heike continued on, navigating the fallen branches and rocks and other obstacles as nimbly as a Rocky Mountain goat.

On Earth, Heike had always been a bulldozer, had always forced Stewart into situations that made him uncomfortable—making him go with her to steal oranges from a tree down the block without her neighbor’s permission, or sneak into swimming pools at fancy hotels where they couldn’t afford to stay, or keep his mouth shut at Vons when she slipped packages of Camembert and expensive jams into her purse. He wondered now if it had been a mistake to let her talk him into leaving his dorm in the middle of the night. He wondered whether, if he’d stayed put and behaved himself, he might have been able to figure out a way to see Anders again.

Two hours into their journey, Heike tripped and cursed loudly in German, and Stewart offered to carry her backpack. It was heavier than he expected, and it wasn’t until later that he discovered everything she’d managed to stuff inside: not just the metal canister filled with water, but also a paper bag full of shelled walnuts, three large pieces of dried ham wrapped in tinfoil, a wool blanket, two ceramic plates featuring Donald Duck and Minnie Mouse, a spoon, two forks, a box of matches, flint, an XL poncho, a pocketknife with a serrated blade and a small wolf carved into the handle, and a photo album Stewart recognized from her condo in Ventana Beach.

She reminded him again that time was of the essence and he forced himself to press on until, eventually, they saw a clearing in the woods on the side of the road. They were both sweating heavily, and she told him he could have three sips of water but no more. “It needs to last us,” she admonished.

On Earth, he would have hesitated to drink after his mother, but here he didn’t make a fuss. He was exhausted, and his back was hurting, and he had no idea what would happen to them. “Will there be food we can eat?” he asked a few minutes later as they crossed through a grove of gnarled, leafless trees that looked like figures rising up from the ground writhing in pain.

“On the train?”

He nodded.

“You really don’t understand what’s confronting you here, do you, mein Schatz? This isn’t Amtrak we’re taking.” She told him the banana and the orange and the walnuts and the ham were their only food, and the water in the cannister was their only water, and he should be grateful. “Do you know how many people have starved to death here?”

He had no idea what she meant, given that they were already deceased. Had he entered some kind of twilight zone where people could die again and again? Since he’d arrived in Heaven, some people had told him that the next life was even more wretched than the place they now lived.

The moon—which seemed somehow larger than it appeared on Earth—was nearly full, and they traversed areas thick with poplars and spruce and towering oak. They crossed a creek where his mother gamboled from one stone to the next, while he lost his footing and landed in the stream, soaking his pants. When she confirmed he wasn’t hurt, she prodded him forward. They crossed a field where, in the distance, he saw what appeared to be moose. They negotiated terrain so sludgy it felt like they were wading through wet cement.

Stewart wondered what Anders was doing then, whether he was at his parents’ house in Maine or back in Europe. Anders was a nomad. This was one of the things that made him so attractive—his unfettered curiosity and hunger for new experiences. Stewart kept wondering why Anders had reached out to him after being out of touch for so long. Was it possible that things with his girlfriend had ended? Was it possible he’d decided he wanted to be more than just friends?

Stewart didn’t want to live with his mother in a hut in the middle of nowhere. The idea of spending every waking minute with her for years on end was impossible to fathom. On Earth, visiting her for just three or four days over Christmas often pushed him over the edge.

He felt a pebble in his shoe and was going to ask to stop when, miraculously, a clearing appeared in the distance; there, before them, were the railroad tracks and a small wooden hut. “Christ,” he called out. “We made it.”

He saw his mother pick up her pace. She looked at her watch and when she got to the railroad tracks, she looked left and right into the distance. “I don’t know if we made it,” she replied grimly.

“We’ll it’s only 5:13. You said the train doesn’t come until 5:20.”

“The times are approximations. Sometimes the trains come sooner, sometimes later.”

Stewart scrutinized the hut: a small structure made of wide, weathered planks with a flimsy wooden door and a single, forlorn window whose glass was covered in grime. “We’ll just wait,” he said, with as much authority as he could muster. “We can wait inside there.”

His mother bent down and felt the tracks with her hands.

“What are you doing?” he asked, full of irritation.

“I’m trying to figure out if the track feels warm or if there’s any vibration.”

“You think the track’s going to feel warm?”

“You have a better idea?”

“Let’s just go in the hut and wait there. I’m exhausted.”

She told him she’d come inside in a minute, after she moved her bowels.

The hut had a narrow bench and stool and, on the floor, a toppled pitcher. In the corner lay a rabbit that looked like it had been dead for weeks. Its skull was intact, but it was eviscerated, its body sliced lengthwise. If he’d had more energy, Stewart would have tossed the carcass outside onto the dirt. Instead, he sat on the bench and opened his mother’s rucksack and took out a piece of the ham, which was thick and well-salted and delicious. He’d taken four bites when Heike opened the door.

“How dare you go into my bag and get yourself this ham without asking me!” she shouted. She looked like a wild animal.

He stopped chewing momentarily. “I’m starving,” he replied with zero emotion.

“What about me? Don’t you think I’d like a piece of ham too?”

“There’s two more pieces,” he said, pushing the bag towards her.

“I know there are two more pieces! That’s all we have! We have exactly three pieces of ham—that’s it. There’s nothing else.”

“I’m sorry. I figured once we got on the train, we’d be fine.”

“How dare you talk to me this way,” she shouted. “Do you know what I’ve been through? Do you? You have no idea what’s happened to me!” She was sitting on the stool across from him, in the dark, and her presence filled the room, weighing down on him like an invisible force. He could see the outline of her body; moonlight made its way into the hut through the gaps in the walls and the window. As she took off her boots, she launched into him, telling him he was selfish and spoiled and had never cared about anyone but himself. “Why do you think these boyfriends of yours keep breaking up with you? Why?”

“What the fuck is that supposed to mean?” he shot back. He realized then that he hated his mother. His prior feelings of tenderness had all been misguided. He’d never been selfish with his boyfriends. If anything, he’d always been desperate to please them.

Heike burst into tears and started rifling through her rucksack and took the photo album out in her soiled hands. “Do you see this?” she yelled, holding it out to him “Take it!”

He hesitated, eyeing the album’s pink cover with the orange tulips.

“Take it!”

He took it from her. “Why?” he said, feebly.

“Why? Because they’re our memories. They’re from our life together when we were close.”

He stared at a soiled rag on the ground.

“Look at them!” she demanded.

“My hands are all dirty,” he managed, looking down at a butterfly on one of the tulips.

“Ach, your hands are always dirty. Watch this,” she said, grabbing her rucksack. She rummaged through her things and a moment later she took out a lighter and flicked it twice until a yellow flame sprang up. She held the flame up and stared at him. “Give it to me!”

He had no idea what she was planning to do. Was she threatening to burn the album? She was a pro at being manipulative, but this was next level. “Mom, please, calm down. Everything’s going to be okay. The train is going to come and we’ll go to that cabin.”

“How do you know the train is going to come? It’s 5:30! The train probably already came.” She slammed her hands on her knees, eyes ravenous.

Apropos of nothing, the image of Raskolnikov using an axe to smash the old pawnbroker’s skull suddenly filled his mind: the hag’s exposed cranium, matted down with gray hair, beckoning him in the pale light of her cluttered apartment, her frail neck inviting him to end her existence. Stewart pictured the axe meeting the crown of the old woman’s skull. He heard her cry out, then saw her sink down to the floor. He imagined his mother collapsing to the ground also, there in the hut, her body crumpling as he fled into the night. He imagined prostrating himself on metal tracks, praying the train would come through at full force and end things once and for all.

When Stewart awoke, his body was stiff from sleeping on the wooden floor. Sunlight filtered in through the small window, and, according to his watch, it was 8:35. He didn’t see his mother, though he heard a thudding sound outside the cabin. He got up, put on his shoes, and opened the door.

Twenty feet away he saw Heike on her knees, in a dirty patch of snow, using a rusted piece of metal to dig a hole. Next to her, on a section of bare earth, lay the rabbit’s body. In the sunlight, the animal’s remains looked menacing: splayed carcass, bulging eyes, bared teeth.

“What are you doing?” Part of him felt contrite for not having been kinder to her when they’d arrived at the hut.

“I’m burying this thing. Come and help me.”

“What’s the point?”

“It’s a dead animal. You want to just leave it out here on the field?”

He was studying her now, taking in her battered face in the sun. “I don’t know. What’s wrong with that?”

“You have a lot of nerve sleeping like a prince, then waking up and questioning me. I’m making a grave for this rabbit. Now will you please come here and help?”

He moved toward her then crouched down, assessing the situation. The hole was already a few feet deep, and he didn’t see any rocks or other tools he could use. “Isn’t it deep enough already?”

She paused and looked up at him, exasperated, her face sweating, cheeks streaked with mud. “Look, I need you to go back to C-12 and find a friend of mine. She lives in Oleander. Her name is Sallie Kleinfeldt. She can help us get out of here. You have to go talk to her and tell her we need her to get us a car.”

Stewart looked at her as if she’d just told him she wanted him to do seven backflips in quick succession.

“We have no choice,” she continued. “The next train may not come for several more days, and we can’t sit here like lame ducks. It’s not safe. You need to go to Sallie and arrange things with her. You can trust her. She befriended me when I first arrived. She has red hair and refined glasses.” Heike stood up and reached into her pocket. “Give her this,” she said, handing him a small package wrapped in burlap and tied with a piece of twine. In the morning light, his mother looked like a corpse—sallow and wizened and frail. He noticed, for the first time, a large scab on her neck.

“What is it?” he asked.

“It’s better you don’t know. It’s valuable. Sallie will know what it is. Tell her we depend on her.”

Stewart felt a pressure building in his skull. On Earth he’d done everything in his power to be careful and prudent. He flossed twice a day, avoided hard candies and peanut brittle, went to the doctor at the slightest sign something might be wrong, backed up the files on his computer obsessively. Now he was supposed to head back to the Precinct from which he’d just escaped? He was supposed to try to get a complete stranger to break who-knew-how-many rules to help them escape? He might as well be trying to cross the Amazon River by swimming through a shoal of red-bellied piranhas all chomping at the bit for their next snack.

Against his better instincts, Stewart began the journey back, cutting across the open field and heading into the woods they’d traversed the night before. He followed the path that led to the stream he’d fallen into just hours earlier. The sun was strong and felt good on his face. He walked quickly, holding the burlap tied with twine tight in his fist.

At some point during the return trip, his watch stopped, inexplicably, and his mind began to spiral. He began to feel lightheaded from hunger, and all he could think about was the ham, how miraculous the slab of salty meat had tasted. He imagined himself spraining his ankle and freezing in the snow, imagined himself getting lost and being hunted down by the men Heike said patrolled this region of Heaven with rifles and German shepherds.

The night before, when Stewart had asked her why, if they were in Heaven, guards were necessary, her reply was laden with bile. “What means Heaven? Heaven is a fable. Call it whatever you want. It’s like wartime up here. In some precincts, people are kept in barbed-wire cages. They starve to death slowly, and their teeth are extracted for gold.”

“Did we end up in hell then?”

“How should I know? What does it matter? Heaven, hell, who cares what it’s called? We’re here, and we must do our best to survive.”

When Stewart was a child, Heike had told him stories about growing up in Germany during the War—how she and her mother and brother had fled Leipzig to escape the air raids, and how they’d lived in a cottage without running water for eight years, stealing grass from a neighboring field to feed their rabbits, having to parcel out a single loaf of bread to make sure it lasted a week. She told him she’d cut holes in the front of her shoes when her feet grew too large, walking miles to attend school.

Three hours into his trip back, Stewart began eating fistfuls of snow, trying to quench his thirst. He thought about his mother’s face and the scab on her neck and the dead rabbit—its protruding eyes, its urine-colored teeth—and about how he’d stood outside the hut, like a fool, watching her dig that ridiculous grave. He wondered whether the authorities had sent out a search party to look for them and what would happen if they found out he’d tried to escape. In the distance he heard a sound and, when he looked up, he saw a flock of turkeys working their way through the brush and the fallen leaves.

The backpack was heavier than he expected, and it wasn’t until later that he discovered everything she’d managed to stuff inside: not just the metal canister filled with water, but also a paper bag full of shelled walnuts, three large pieces of dried ham wrapped in tinfoil, a wool blanket, two ceramic plates featuring Donald Duck and Minnie Mouse, a spoon, two forks, a box of matches, flint, an XL poncho, a pocketknife with a serrated blade and a small wolf carved into the handle, and a photo album Stewart recognized from her condo in Ventana Beach.

Eventually, when Stewart was certain he’d become lost and would never reach C-12 again, when the sun was high in the sky and his stomach was churning with hunger, he saw the Precinct’s austere concrete buildings in the distance. He tried to figure out what he’d say if someone saw him going back to his room covered in mud. He imagined being shot in the skull, and he wondered if he should turn around and go back to his mother, but he knew he had to press on. He still carried the burlap in his pocket and, though he’d been curious to know what it contained, he’d resisted the urge to undo the twine.

Somehow, against all odds, he found himself approaching and then entering C-12 without being seen. Picking up his pace, he crossed the field leading toward the buildings, then the parking lot. His eyes fixed on the ground, he passed a large faded mural on the side of a tall building with an image of a boy in a blue uniform running with a kite. When he arrived in his room, he locked the door, breath rapid and shallow.

He sat on his bed, terrified, looking at the linoleum floor and the shag carpet, listening for sounds in the hallway. He took out the ID card his mother had given him, wondering who Amos Pierce was and what she’d done to get the ID. He knew he didn’t have the luxury of allowing his thoughts to unravel, however, that he needed to put his shoes back on and find Sallie Kleinfeldt, or whatever her name was, as quickly as possible. He examined the package his mother had given him and wondered whether it contained something precious. It weighed almost nothing and seemed too small to hold a cell phone or any electronic device.

His hands and clothes were filthy. He took a deep breath and made his way to the shower, got in and turned the water to hot. The shower curtain was opaque, and he kept pulling it back to make sure no one had followed him. He pictured someone waiting for him in the bathroom with a knife. It had been nearly a week since he’d jacked off, and he imagined Anders mounting him. He saw before him Anders’s muscled chest and his shaggy hair, and his impossibly beautiful penis.

Stewart knew men weren’t allowed in Oleander, but, at this point, that was the least of his concerns. If Sallie Kleinfeldt chastised him for breaking the rules, he’d plead ignorance. He had no other options. He knocked on her door and waited.

Moments later, he heard a woman inside the apartment ask—obviously irritated—who it was. He identified himself, and started to explain the situation when the door flew open and the woman cut him off. She had gray hair pulled back in a ponytail and a mohair sweater with a green palm tree on the chest.

“You realize you shouldn’t be in this building, don’t you?”

He nodded, and she told him he could come in for a minute. “But just one,” she added, standing in her dimly-lit hallway. Her tongue was probing her rear molars as if she were in the middle of eating.

Stewart spoke quickly, heart pounding.

Sallie looked at him skeptically. “Do you know what the punishment is for trying to escape? What makes your mother think I can even help you two get a car? What gave her that impression?”

“I’m sorry,” he said, sweating now. “My mother told me you’d be able to help us. She wanted me to give you this.” He handed her the small burlap package, and she stared at it.

“What’s this?” she asked impatiently. Quickly she undid the twine and opened the package. Inside was what looked like a diamond the size of a small apricot: even in the dim light, it sparkled brilliantly. Stewart felt his heartbeat quicken. He’d never seen a diamond this large before, and he wondered where his mother had gotten it.

Sallie’s eyes lit up, and she smiled, revealing most of her teeth. She took the gem and held it up to the ceiling light. “Is it real?” she asked. The apartment’s air smelled of asparagus and onions.

“Who is it?” a voice called out from the living room. The voice was familiar, and Stewart realized it was Margaret, the woman he’d met when he first arrived in Heaven.

“It’s the German woman’s son,” Sallie called out. “He says he needs help.”

Margaret came into the hallway, holding a half-eaten lemon square. “The New Yorker?” she exclaimed, chewing. “You’re the German lady’s son?”

He nodded.

“Heavens to Betsy. That woman is a handful.” Margaret had on a bright orange sweater, along with the same magenta scarf she was wearing when Stewart first met her.

“He’s asking whether I can get him a car,” Sallie said.

“A car! Why on Earth does he need a car?”

Sallie started to explain and showed Margaret the diamond. “Where’d she get this?” Margaret asked, taking it and holding it up to the light. Her skin was chapped, and there were deep cuts on her fingertips and knuckles.

“She got it from a man in C-23,” Stewart said, deciding he needed to adopt an air of authority and conviction. “She traded it for some jewelry.”

“Honestly. Ding-ding-ding,” Margaret replied, wagging her left index finger high in the air. “Know what that is?”

Stewart shook his head.

“It’s my bullshit detector.” She handed the stone back to Sallie. “You better check this. No way they had a diamond like this up there.”

Stewart’s mouth suddenly felt like it had been stuffed with cotton and, as Sallie headed through the living room into what he assumed was her bedroom, his entire body began to perspire.

“Well, you might as well come in and have a seat,” Margaret said, heading back into the living room. The room was spacious and had a beautiful couch that looked like it might have come from 1930s Vienna—red velvet upholstery and carved wooden legs.

“Wanna cookie?” Margaret asked. She gestured to a small plate on the coffee table piled high with lemon squares and chocolate chip cookies and what looked like pecan sandies. Stewart thanked her and took one of the lemon squares, feeling the intensity of Margaret’s gaze on him as he sat in the armchair farthest from the couch. She asked him how on Earth his mother had escaped C-23. “You realize there are rules against aiding and abetting?” she said, leaning forward and taking two of the sandies. “Serious penalties.” Her fingers were knobby and crooked, and he noticed a small round scar on the top of her right hand, a cigarette burn maybe.

“I’m sorry,” he stammered. “I didn’t realize that.”

“Well, it’s common sense to most people, but live and learn. What’s taking you so long?” she yelled out at Sallie.

“Coming!” Sallie said, hurrying back into the living room. “I had to find my loupe.”

“So?” Margaret said. “What’s the verdict?”

“Looks like quartz to me.”

“Let me take a look.” Margaret got up and took the rock and the loupe over to a small wooden desk with a lamp. There were four paintings on the wall: a still life of a vase of flowers, and another of a bowl of cherries and some dates, along with a landscape of what looked like the Scottish Highlands. The fourth painting showed a fisherman proudly holding up a large pike in his bare hands. The man was standing next to a wooden rowboat on the shore of a body of water, grey clouds in the sky, and in the distance, tall cliffs rising up from the ocean.

“It’s quartz all right,” Margaret said. She made a tsking sound. “Figures. I knew she was trouble from the minute I set eyes on her.”

“You realize what this means?” she asked Stewart.

He shook his head.

“It means she’s trafficking in counterfeit goods—in addition to everything else she’s guilty of.”

Stewart said he didn’t think his mother was trying to trick anyone. He said she was old and exhausted and hadn’t done anything wrong.

“Hasn’t done anything wrong?” Margaret guffawed. “Ha! She’s done plenty wrong. Why else do you think we put her up in C-23? She’s a troublemaker, and you, my friend, are an accomplice—whether you like it or not.”

“But we were just trying to go to her hut. What crime did we commit?”

“You were given a handbook when you arrived. Section 3.45, subsection (a) clearly states people are not permitted to enter or vacate a Precinct other than their assigned Precinct without written permission from the Office of Reconciliation. Did you have a letter from the Office of Reconciliation?”

He shook his head.

“Of course you didn’t. Did your mother have a letter?”

He shrugged.

“Of course she didn’t.”

“That makes you both criminals. Now, granted, her crimes are more serious, but you’re both culpable. They’ll have a trial, of course, and you’ll be asked to testify. You can tell them she took you against your will, but who knows how much it’ll help. Depends on how cooperative you are, I suppose. I don’t make the rules.” She used a napkin to wipe the crumbs from the sides of her mouth.

He looked at the two women, who were now sitting next to each other on the couch, staring at him. He told them he was sorry, trying to think of something to say that might change the conversation’s direction.

“At this point, apologizing won’t do much good,” Margaret continued. “And neither will your tears.” Then she asked him to tell her what exactly Heike had told him about the hut and the particulars of her departure from C-23. Margaret wanted details—wanted to know who’d sold his mother the hut and how Heike had managed to get out of C-23 and who the farmer was who’d helped her escape. As he spoke, he stared at the painting of the fisherman, and grew increasingly detached from his presence in the room, until eventually it felt as if the entire conversation were taking place behind a wall of thick glass. He could barely hear what Margaret was saying, because he knew that soon enough he’d have to provide a detailed accounting of his mother’s arrival to his room the previous evening, and their journey to the train tracks, and anything else that seemed relevant, and he wanted to make sure he kept a clear head so he didn’t say anything that might be used against him if there did end up being a trial. The small lamp in the corner filled the room with a yellow light that cast shadows across the women’s faces and made it hard to see whether they were looking directly at him or at something else.

The room grew increasingly hot. Stewart thought he smelled smoke. The air in his lungs felt thick, the lamp radiated heat. He imagined orange flames moving up the walls of the living room, consuming them all. Meanwhile, these women continued to interrogate him, chewing and talking, chewing and talking.

Years later, after his mother was apprehended and the trials were held, Stewart would remember looking at these women and feeling the room grow hotter and hotter, like a kind of inferno. He’d remember Sallie chewing one of the cookies, and the crumbs on her lap, and he’d remember how damp his clothes grew from his perspiration.

This memory of smoke and heat and fire would stay with him long after his confession and his betrayal—he guarded it closely, because it was the last memory of warmth he would have.

The place he and his mother were kept in confinement was perpetually cold, with its concrete floors and steel walls and its lack of blankets and heat. Outside, he pictured nothing but fields of ice and of snow. He and his mother lived thusly for decades, it seemed, maybe longer. They slept holding one another, grateful for the modicum of warmth each provided the other in that region of Heaven so distant and forlorn that it was not even considered a Precinct.

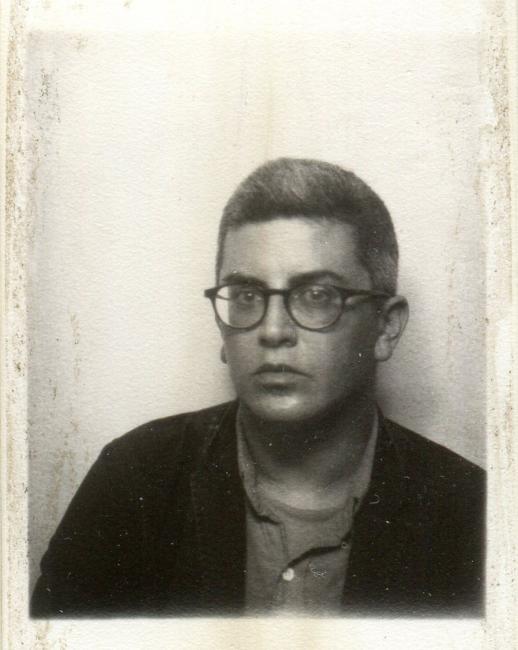

Lauren Simkin Berke is a Brooklyn-based artist, illustrator, and educator whose clients include the New York Times and Smithsonian magazine. Berke teaches in the MFA Illustration program at the Fashion Institute of Technology and in the BFA Illustration programs at Parsons and the School of Visual Arts.