Live Alone Death

…even a skeleton must be formally declared no longer living.

— N. R. Kleinfield, The New York Times

In Tokyo, Miyu Kojima angles an adjustable lamp to flood the scene with light.

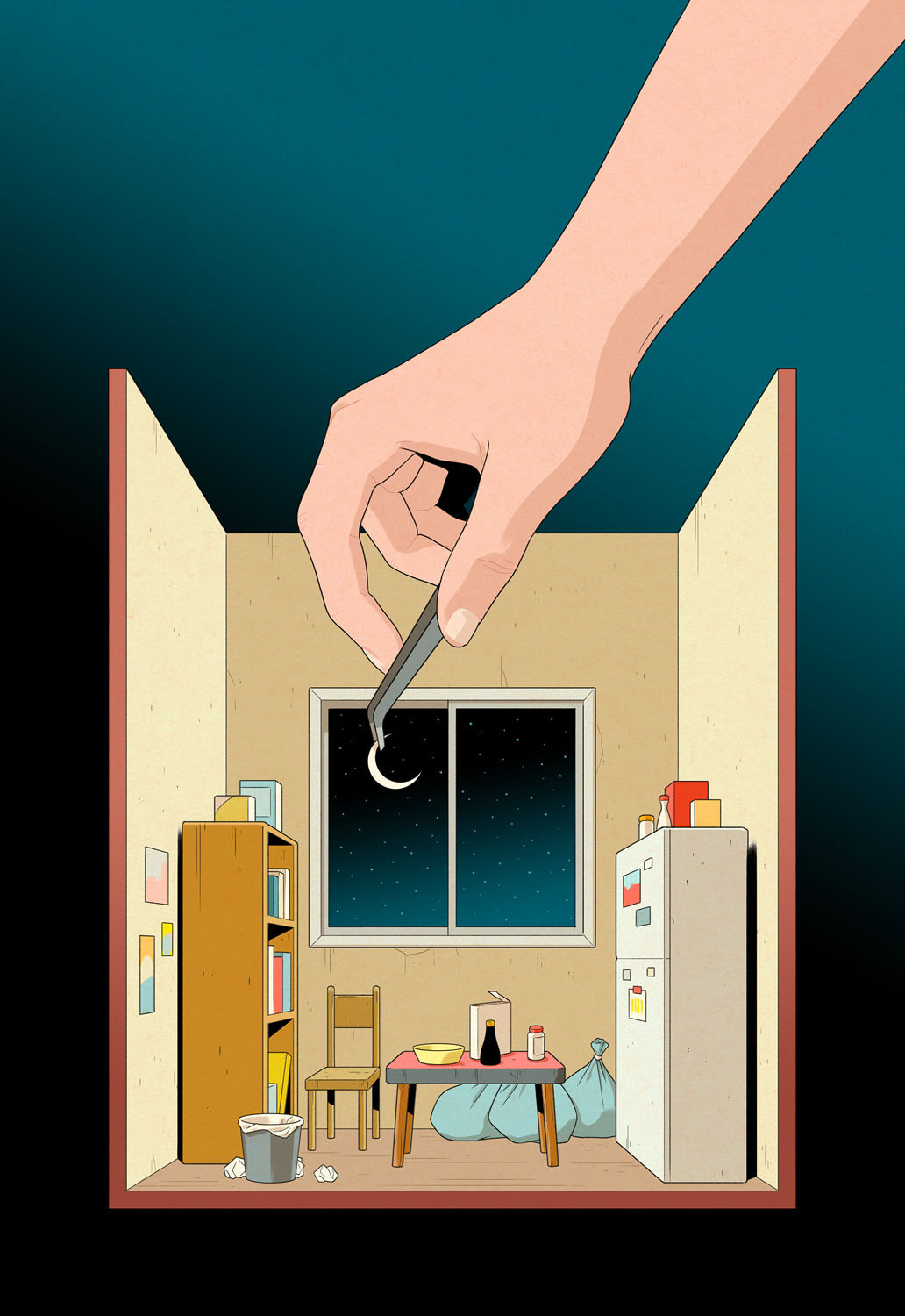

Before her: a scaled-down replica of someone else’s life; the interior of a room on display, with the art of diorama as an exercise in stillness. Miyu leans in, steady, contained, her breathing gone slow in the body—so as not to disturb the moment she’s sculpted piece by piece over the course of the past month. She breathes in the invisible, which her body metabolizes before exhaling the invisible, though it has changed in ways that can only be measured at the level of the atom. Miyu studies the miniature refrigerator, which is small enough to fit in the palm of her hand; the calendar on the wall with its pages frozen in thought; a round clock the size of a thumbnail with its arms stilled at 1:25. Miniatures like these are often crafted entirely from balsa wood and foamboard, from beads of glue set in place with the tip of a toothpick, just as I imagine Miyu emplacing the smallest drops of rain. She’s created miniature butterflies and miniature newspapers from thin sheets of plastic and acrylic, each piece a replica of form and function, cured in resin and carved with the beveled steel of a utility knife. And to see this vision through, from the first piece to the last, she’s had to inhabit the art of patience.

When Miyu leans over the diorama, she gazes into the opened apartment of a pensioner from Tokyo’s Ueno district the way a surgeon might view the interior of a patient’s body laid open by the careful application of a scalpel. By day, she works for a company specializing in cleaning and restoring homes after unattended deaths occur. Think: people dying alone. Heart attacks, embolisms, strokes, suicides. People slipping barefoot on wet tile before cracking their heads with such blunt force they never wake up. The body assuming its final form. And yet, in all her dioramas, the dead themselves are strangely absent. The bodies of the dead acquire a visual silence, a sacred presence within the scene, and that presence is imbued within the objects of the rooms they once lived in, as well as the rooms themselves.

What I am describing is an artist working through the aftermath of her own father’s death. I’m detailing the brushstrokes and the composition of the diorama as Miyu rebuilds the hallowed room to a scale the mind might comprehend. What I am describing is a nested scene within yet another nested scene.

In the language of film, editors might call this device “embedded narrative.” I think of it more as memory manifest and translated into tiny sculptures of milk cartons and bottles of fish sauce, laundry baskets, rotating fans, vacuum cleaners, bookshelves with story after story tucked inside of them, waiting to be read aloud once more, given back to the air.

There is an intimacy and a solitude to Miyu’s dioramas that pull the viewer ever closer. They contain tiny atmospheres. They serve as meditations on absence. One room to another, each with a stillness implying all that once was. The word after like a fine dust that has begun to filter down.

One of the most extraordinary cases of someone lying dead and unnoticed in their home took place in Zagreb, Croatia, where Hedviga Golik lay dead in her bed for as long as, by some accounts, forty-two years, her neighbors oblivious to the dead woman’s body in an attic apartment above them. I was born a year after she died, and she wasn’t discovered until 2008. The curved glass of her TV set had long since turned brain grey with dust, as in the dark of the mind gone silent, through the landing on the moon, the rise of prog rock, the Jackson 5, ABBA, and disco, through the fall of the Soviet Union and the war in Yugoslavia, the European Union, email, cell phones, and, and, and. While she remained dead and alone in her apartment, I graduated from high school and became a stoner. I dropped LSD and studied psychophysiology and wrote poems in lost notebooks and joined the Army, and, during the cold winter at the end of the millennium, I served as a NATO peacekeeper in northern Bosnia—about a four-hour drive from her attic flat in Zagreb. While I stood in the snow and counted down the end of one thousand years and the beginning of another, there at the hinge-point of two millennia, Hedviga lay in the stillness of her tiny flat, skeletal and mummified and strange even to herself, as her life was slowly buried under layers of dust, year after year, while in the rooftops above the city, the air burst open with light.

It’s hurricane season in Florida. Summer 2025. If I were to die right here and now, mid-sentence, my heart seizing as I sit in my living room listening to music with the shades drawn and a lamp casting an amber glow, there’s a good chance my body wouldn’t be found until long after. Three or four weeks, minimum. And that’s only because I’m scheduled to teach at a local university in the coming weeks. But even that assumes a kind of deadly rescue.

What if, instead of dying inside my home, I were to drop dead at a local park? Twice each day I walk my dog—a golden retriever named Dene—either in the streets around my home or in a neighborhood park farther away. What would happen to her if I had a stroke and flatlined under the halogen arc of a streetlamp? Most likely she’d be turned over to the pound. Surely, there must be a better way than this?

I want to be clear: This meditation on dying, and especially dying a solitary death, I don’t share it to garner sympathy or pity. It’s not a ploy to pull from the well of empathy. I’m simply trying to visualize and apprehend the days in front of me with clarity and realism. I’m trying to gauge what volition I might have in the matter.

I share this because I have a feeling you’ve thought of this too. Or you will.

What if Miyu Kojima made dioramas of my own house afterward? Perhaps from photographs taped to a wall over her modeling desk. How would she depict the rooms of my life, and what gestures to the profound would they hold within, visible to a stranger’s eye?

I imagine it’s late at night in Tokyo, and Miyu feels restless. She’s given up on sleep. Her hand holds a paintbrush as high as the canopy of the golden rain tree outside of my home. The diorama doesn’t include the tree, but it does have a view into my living room and bedroom, or so I imagine. Two Atlas moths, reduced in scale for the scene, appear framed and hung with their wings outstretched on the bedroom wall. On the bedside table, a blue mosaic lamp suspended from a moon-shaped stand. A glass of water. A novel splayed open with a pen and notebook beside it.

Miyu yawns and cracks her neck from side to side. The humming engines of Tokyo drone on around her as she works to sculpt and paint and glue pieces in place. A story begins to emerge. There is a curled indentation on the left side of the bed, a divot at the center of the pillowcase, the signature displacement of the body in space, maroon like the sheets, made of cotton and dyed the color of wine.

Without me, the objects of my life untether themselves from meaning, just as I, too, untether from the world of memory, the world of history, the living world we inhabit. Even the imagination, that last place of refuge. The way it is for us all.

In the living room, in a separate diorama on Miyu’s workbench, a tiny rust-colored leather couch sits under a framed photograph of two lovers kissing by the Cliffs of Moher. Photographs of friends and family rest atop a bookshelf crammed tight with books. Gaston Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space. Alain de Botton’s The Architecture of Happiness. Alexievich. Babchenko. Didion. Dungy. Hemon. Laymon. Solnit. Shelves are recessed into the walls, just as they were when the house was built in 1949, and those shelves hold a Tibetan horn hammered in copper and brass, a fossil slab with two fish preserved in geologic time. On the walls nearby, carved wooden spoons done in the old sailors’ style, with looped rings and lockets and hearts and lyres serving as coded messages for those they love.

Miyu’s attention to detail and the care she brings to each object in the scene is overwhelming. In miniature, she’s rebuilt the high table I created out of large cutting boards and galvanized plumbing pipe. A tiny laptop sits idle beside a cup of coffee. An opened notebook contains the last sentence I will ever write. And I imagine the pen that sits there, so small Miyu had to dip it in glue and ease it down into the diorama with a pair of tweezers, and that pen continues to hold a reservoir of words that will never find their way to the page.

It is the sad and beautiful museum of a quiet life. Without me, the objects of my life untether themselves from meaning, just as I, too, untether from the world of memory, the world of history, the living world we inhabit. Even the imagination, that last place of refuge. The way it is for us all.

In Japan, there’s a term related to the phenomenon of lonely deaths: 孤螂死, or kodokushi. It translates to something like “lonely death.” A similar term, 螂居死, or dokkyoshi, is equivalent to “live alone death.” This translation posits a curious architecture: Solitude is a tether that spans the chasm between life and death.

In the Netherlands and in Belgium, the art of dying includes a poignant ritual I first learned about from Dutch poet Erik Lindner. The practice is known as a Lonely Funeral. I first met Lindner at a poetry festival in Chennai, India, in December 2017, and as we walked through the suburban streets of the city one morning, he described how poets in Amsterdam have volunteered for the “pool of death,” as they refer to it—they are on call and ready to write poems for those who die alone, for those whose bodies remain unclaimed by friends or loved ones. In such cases, a poet drafts a poem to memorialize the dead, and after reciting these verses over the grave, the poem is then buried with them.

Lindner described a poem he’d written for a man who died in a shallow pond under mysterious circumstances, in water only twenty inches deep. This happened near the Vondelpark in central Amsterdam, near a teahouse shaped like a UFO. Lindner had struggled to find his way into the poem until he visited the pond and discovered the statue of an armless woman nearby, a woman made of stone who forever stares over the site where the dead man took his last breath. As Lindner described the woman in stone, his hands shaped the invisible as if he were sculpting her in the air before us. Then he said, of the dead man in the water, “I sort of imagined his last moments before he died, and what happened after. That’s the poem.”

I envisioned the scene as Lindner spoke. I imagined the man dying that night, in the ambient light of Amsterdam, the trees unmoving, their leaves like silver tongues gone silent, the trees as still as the woman made of stone. Even after his body was carried out by forensic specialists and buried with Lindner’s verses, I imagined the woman in stone keeping vigil over that now hallowed place, where the water still moves, the waves lapping the shore in slow undulations, as if the dead man’s displacement continues to make its presence felt.

It is such a strange thing to witness—the aftermath of someone’s death. Even now, I imagine waves rolling outward before curling back in on themselves. The restorative nature of it. The landscape in conversation with the dead man’s life. Wave by wave the water rolling out to the lip of the earth before returning to that hollow space where the dead man sank his eyes into a reservoir of silence from which he never returned.

And the woman in stone? She watches over this fluid meditation until the water once more becomes a glassy mirror that might hold the sky.

What does it mean to have one’s death be curated? To have such deep attention given, with such care to the details, to have another human being offer wonder and curiosity to the event? I find it hopeful somehow. I’m not sure why. I suppose it’s because any one of us might have, no matter how lonely the death we experience, someone there to witness us. To see us. To offer wonder at the crossing, at the closing of the day, at the hour we step into silence.

Maybe this is what I have been trying to accomplish my entire life as a writer. Drafting the details of the living world I hold so dear, saving as much as I can in language before it all goes under, before it fragments and vanishes save for what little we might store within the vault of memory. Though even that is doomed, of course, as the soft architecture of the body is undone by time and dissolution, from tissue and bone down to the covalent bond.

Still. The irony of our temporal nature isn’t lost on me. How fragile and transitory we are. And yet we are composed of the primordial. Carbon. Hydrogen. Oxygen. Phosphorus. And so on. In our bloodstream, elements of iron we’ve inherited from supernovae that burst in the black void of the early universe. Protons. Neutrons. Forged in nucleosynthesis.

Which is another way of saying: Why is it we feel so singular and alone? And when we talk about death, what are we even talking about?

Maybe the tether in kodokushi isn’t made of solitude connecting two states of being—life and death. Maybe solitude is the journey we take to remember that life and death are of the same unified field.

My own perfection of solitude contains a measure of pride I won’t deny; it’s something I’ve honed and polished since childhood. But in this looming and inevitable situation, when the failure of the body lingers in my thoughts, it’s clear that I’ve left too much undone or unrealized, from the mundane to the transcendent, the profound, the sublime.

Simply clearing out my house would require a back-breaking amount of time and effort. The treasures around me are precious, watermarked with love and experience, with days gone by. But for anyone else? Without me, the guitars are just guitars, rather than instruments loved ones once played to awaken the neighbors or shake the gods with lightning and thunder. A mattress becomes a mattress again, and not the coiled plane of dream I’ve known it to be—where I visit the dead I love before vanishing each night into the void we all carry within. Soon enough, that place of dreaming will be thrown into a dumpster and given to the county landfill, just as my body will be given to fire and transformed into vapor and ash, my ashes then given to the earth and wind.

This is what I’ve been thinking about.

The lyric care we give

to the lonely. Each soul in the crossing.

Each signature, vanishing.

The created thing we call our lives.

Where we live. This housing

of time. Protons. Neutrons.

The invisible all around us. Simple as air

breathed in, breathed out. Days,

months, whole decades.

This thing we call solitude. This thing

we call a life.

The word after. Where the trees leaf out

in green. Landscapes

draped in sun and shadow. The eye

of the moon in the broken motion

of clouds, bright and curious in one moment, turning to dream

in another. This is the way things are. Each glimmer, caught

as if in amber, the world moving on

around us,

our ears gone deaf to its many engines.

Anuj Shrestha is an illustrator and cartoonist currently residing in Philadelphia. His illustration work has appeared in The New York Times, The New Yorker, The Washington Post, ProPublica, McSweeney’s, Wired, and Playboy, among others. His comics have been listed in several editions of...