Don’t Be a Square

Scientific progress is fitful, uneven, and slow. Public awareness follows belatedly. Culture comes last.

It was in 1856 that Eunice Newton Foote, a pioneering suffragist in Seneca Falls, NY, observed that increased atmospheric carbon dioxide would warm the planet. The Swedish chemist Svante Arrhenius made the link to fossil fuels in 1896, but it took another six decades before the American scientist Roger Revelle warned that a hotter planet might have rather negative consequences for human civilization. Scientific consensus on climate change arrived in 1979 (crystallized by the Carter administration’s Charney Report), but widespread public alarm didn’t set in until 1988, on the hottest June 23 in the history of Washington, DC, when NASA scientist James Hansen told the US Senate that global warming was no longer a theory—it had already arrived.

In the thirty-five years since, the public imagination of climate change has been dominated by a single genre: dystopia. This is to be expected—it’s human instinct, when faced with bad news, to leap to worst-case scenarios. And climate change has kept up its end of the bargain. It has delivered the worst: the worst fires, hurricanes, floods, droughts, and extinction crises humanity has encountered, with each year worse than the next and the promise of much grander devastation to come. One would anticipate novels, films, and visual art depicting Category 5 hurricanes and plagues and parched exoduses across post-apocalyptic wastelands, and that is mainly what we’ve received.

But dystopian art, for all its finality, is never a terminus. It is just the beginning—a subgenre of fantasy that abhors nuance and delights in extremes. Dystopias instruct and entertain but they are a blunt tool and, over time, go the way of all childhood fascinations.

The cultural history of the nuclear age offers a guide. In 1951, six years after Hiroshima, the first nuclear dystopias hit American movie theaters. Their pace accelerated through the decade; On the Beach was published in 1957 and filmed in 1959. Five years later, Stanley Kubrick isolated the comic absurdity in the premise of mutually assured destruction (Dr. Strangelove, 1964). But it was an additional twenty years before Don DeLillo could write a novel (White Noise, 1985) about how atomic anxiety had infected the national consciousness. The world didn’t need to wait for a nuclear exchange; the mere threat of one was sufficient to warp daily life in unpredictable and far-reaching ways. With that recognition, nuclear art had reached its maturity, forty years after the Trinity test.

Margeaux Walter’s photographs don’t instruct, warn, or harangue. They ask questions—personal questions. Most critically: How has our sense of reality already been deranged by climate dread?

Our sense of reality has become, in a word, shaky. Winter is uncannily mild. Spring is summer. And summer…summer is demonic. There is nothing “natural” about the natural world; the term “natural world” has become a bleak joke. Every square inch of land and atmosphere bears our smudged fingerprints. If Walter’s photographs alienate at first glance, it is only because they manifest the weirdness of a planet behaving utterly unlike itself. The planet is behaving, instead, like us: erratic, confused, callous, violent, vengeful.

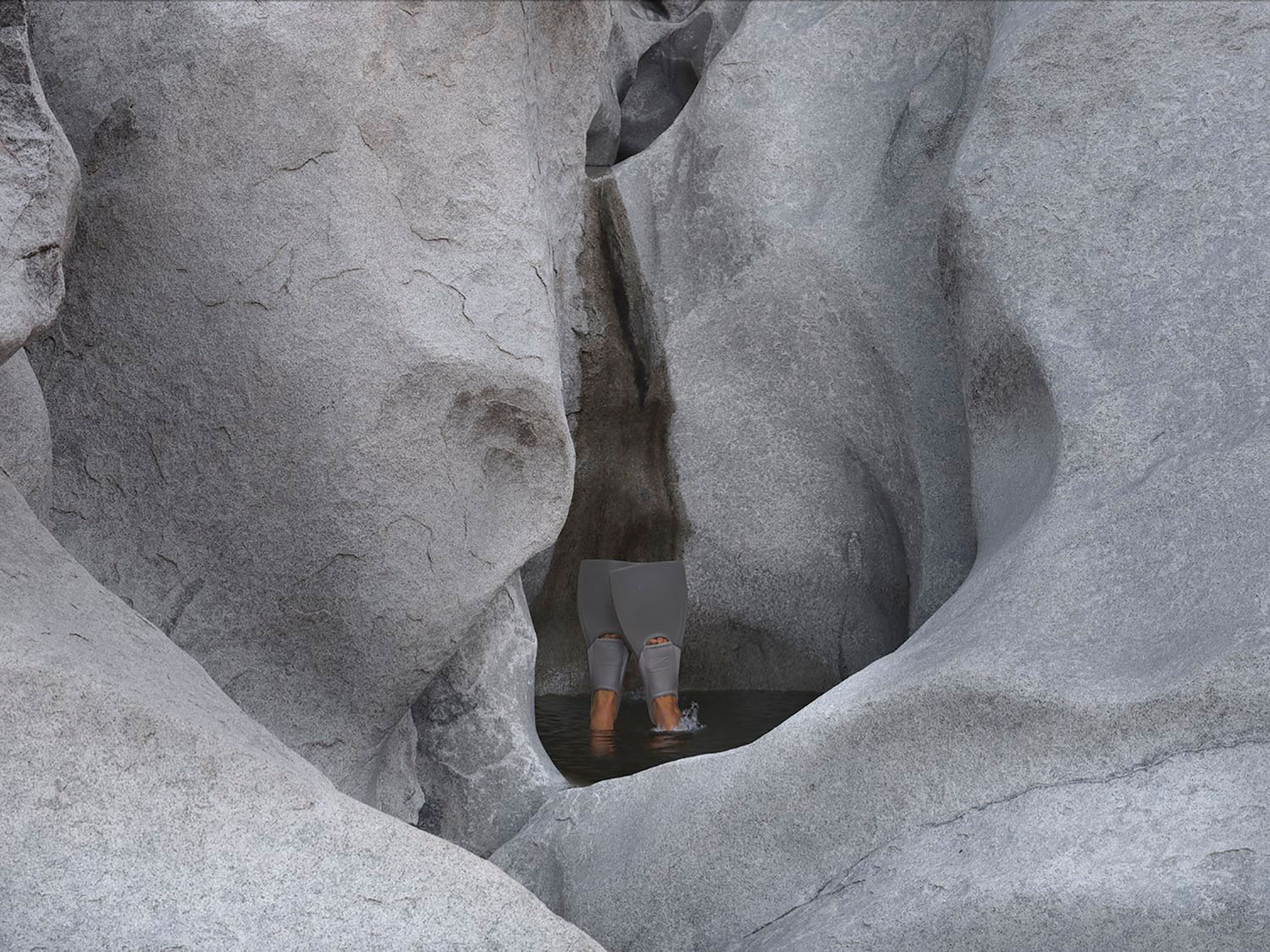

In the series Don’t Be a Square, Walter has found a visual language for this uncanniness. The photographs present a majestic, often symmetrical landscape, only something is off. The something is a person—Walter herself—who seems to be trying, and failing magnificently, to blend in. The colors don’t quite match: The DayGlo orange stand in Juice Bar is a garish send-up of the burnt sienna of the desert mountains lit by the falling sun; the synthetic green wig in Yucca mocks the bright detonations of sharp leaves around it; the gray diving fins in Flip Flop are pallid companions to the folds of richly textured rock that engulf it. We can’t reproduce the majesty of the world we inherited; we can only simulate it. Crudely.

There’s tragedy in this realization—a tragedy that any conscious person must, at some point, confront. There’s no going back to the nature ideal, the illusion of wildness and purity. It was always a myth, of course, a vestige of the Romantic age, but in landscapes like the ones Walter photographs it could be entertained for a time. That time has passed.

Walter’s photographs suggest a perverse and not entirely dispiriting alternative. Might we be able to find sublimity in this ruin? Or even freedom, majesty, a sense of the sacred? Might these qualities, which we’ve come to associate with untrammeled nature, be carried over into a damaged world? Is it not, at the very least, worth the effort to try? Our landscapes might be compromised but our art needn’t be.

Margeaux Walter’s work has been exhibited at such institutions as MOCA, the Butler Institute of American Art, Tacoma Art Museum, and the Griffin Museum of Photography. Her work has been featured in publications including the New York Times, WIRED, the Wall Street Journal, the Seattle Times...