The Opal Cleft

Here was Cyrus at the door on a Saturday, unannounced and with a leather duffel hanging from each arm, asking to crash for a night or two—three at absolute most. In the half year since Theo had last seen his cousin, Cy had perfected the all-over look of bohemian tragedy: down ten pounds he couldn’t afford, a premeditated shabbiness to his winter coat, and his hair tied back with a shoelace. He had shows coming up in DC neighborhoods Theo recognized vaguely by name; at the last minute, his Airbnb had fallen through, and then his phone had died on the bus ride down from Brooklyn—“so thank God you were home,” he finished, breathless. “Is it okay?”

“Sure,” said Theo. He stepped aside, flooded with gratitude as Cy entered the apartment. Saturday these days meant cleaning, a relentless litany of tasks that required rubber gloves and had to be done well for the subsequent Sunday to be worth a damn. A distraction was welcome. He peeled the gloves from his hands and took one of Cy’s duffels, deposited it near the sofa.

Cy looked around, his eyes widening at the folded afghan on the sofa, the framed photos lining the bookshelves. “Look at you, Mister Lives-with-a-Woman! Is she home? Should you ask first?”

It was a smart question, but Theo bristled anyway. “She’s at brunch,” he said. “I’ll text and make sure.” Though of course the answer would be a thirsty-ass yes, Aja long having hoped to meet this particular cousin of Theo’s. Thanks to YouTube, she was a superfan. One of those twenty-five- to thirty-four-year-old women whom Cy found charming at his shows except when he didn’t, who drank too much on empty stomachs and tipped stupidly well but got their low-hanging earrings snagged in his good wigs when he agreed to photos. Theo wondered whether to warn him about Aja’s fandom, to manage expectations.

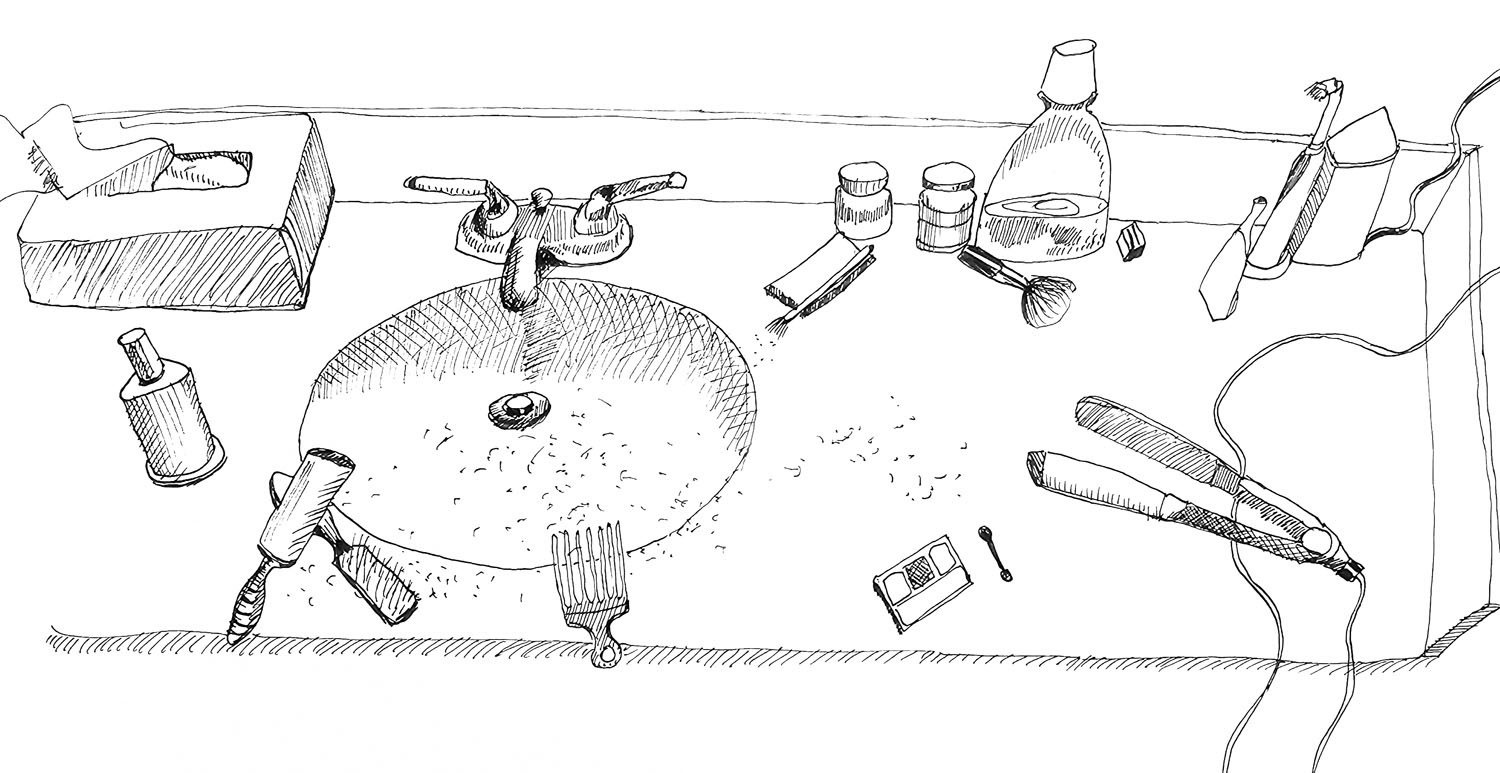

But Cy had already plugged in his dead phone and installed himself in the newly scrubbed bathroom, where he now spilled the contents of a vinyl makeup bag across the sink. “If it helps,” he said, “I can get you guys tickets to one of the shows. Tonight’s sold out, but probably for tomorrow? Or Monday or Tuesday?”

Theo added this proposal to the text he was drafting, leaving out the Sunday and Monday offers. The whole point of cleaning the house on Saturdays was to reserve the next two days for the catatonic consumption of football and takeout wings, one of few rituals that had survived Theo’s move from Brooklyn into Aja’s U Street apartment.

And on second thought—he hesitated at the part about Tuesday too. For Tuesday evening he’d loosely slated drinks with Brandon and Tiffany, old college friends who’d both recently made manager at their respective consulting firms and seemed poised to reach down a hand. Engaged, too, to each other—which meant Aja’s presence would be expected if not mandatory.

But drinks with Brandon and Tiffany, if done correctly, could be contained to a neat ninety minutes; long enough to connect and get loose, not long enough to get sloppy. Anyway, how often was his cousin in town? Basically never. Theo cleaned up the text, skimmed it, pressed send.

“Tonight you wouldn’t like, anyway,” added Cy, yelling a little over the whine of his electric clippers. “Seems like a pretty white crowd, bunch of girls doing Top 40, you know? But on Tuesday I’m soloing at Maisie’s. Jazz. Not sure what your lady’s into, but I’m thinking that’s more your speed?”

Theo’s phone buzzed, a reply from Aja: Omg YAY! Everything clean, right?

His mind cast back to the previous Saturday, a brief but irritating fuss over some grease buildup on the stovetop. He retrieved his gloves from the counter.

“Wipe up when you’re done, man,” he called out when, a few minutes later, the clippers went silent.

“Of course.” Cy leaned out of the bathroom, the point of his chin coated in honey-colored powder. “Oh, and thank youuuu,” he trilled in a voice Theo recognized from their roommate days, when he’d half watched dozens of these metamorphoses on Cy’s show nights. In the early stages of transformation, Cy basked in the playfulness of it, trying on ever-campier personae as his face disappeared incrementally behind the makeup. Another eight layers of paint or so and he would no longer be Cy but Heaven, azure shimmer everywhere, highlighter dappling her cheekbones; and her speaking voice would follow suit, a languid contralto like a cloud floating majestically past. Or so it had been explained to Theo. And that was to say nothing of what happened when whichever wig went on, the inexplicable shoes. Cy already stood even taller than Theo, a willowy six-foot-four, the extra height inherited from the towering Danes on the other side of his family tree. Heaven on heels was a spectacle. Aja would lose her mind on Tuesday.

Aja. “Anytime,” said Theo, and leaned in close to inspect the surface of the stovetop. Clean, as far as he could tell.

“Oh, Jesus Christ,” said Aja, skimming a towel across the bathroom sink. She held it up to show Theo, the hot pink microfibers matted with stubble and powders. “He saw the bathroom like this?”

Theo paused the TV. “Babe,” he said, keeping his tone light. “He left it like that. I just haven’t gotten around to cleaning it again.”

A brief silence as Aja confirmed that the hairs on the towel were Cy’s, fine and sandy, and not Theo’s coarser, darker ones. “Ugh, oh well,” she said, and came out to nestle on the sofa beside him.

Her head was heavy and her voice raspy from an afternoon’s worth of brunch cocktails, which could have one of two diametric implications: either she’d be all talked out, her girlfriends having absorbed her every microdroplet of gossip—

“Oh my God,” she murmured on his chest. “You wanna hear what Brielle said?”

—or else exactly the opposite. Someone would have pissed her off, necessitating a meta-download. Brielle was the only other Black associate at Aja’s firm, and thus a necessary ally. Big, unwieldy breasts and no ass. Who, at the house party Aja had thrown to celebrate Theo’s move in, had more than once let a hand graze Theo’s dick when they found themselves together at the drinks table. On this point Aja escalated over the next few months from incredulous to defensive until Theo finally dropped it, baffling though it was, her protectiveness of this person who he quickly learned was desperate and predatory as fuck around partnered men, which Aja herself had been quick to point out—but anyway. These days he kept his distance.

Aja had propped herself up on his chest with both elbows and now stared at Theo, her dark eyes wide and lovely and sparkling with brunch makeup. “She said”—fruit and syrupy liqueur on her breath; Bellinis, he thought—“that if Kyle doesn’t put a ring on it by her birthday, she’s getting her IUD out anyway. She already has the appointment. Kyle has no idea, and we’re all, That’s fucked, but then again, what’s she supposed to do? Give an ultimatum, admit defeat and strap in for, like, four to seven miserable years of resignation?”

There was a Kyle? Theo had never heard of Brielle’s having any sort of relationship within striking distance of an ultimatum. “Wow, babe,” he said. “That’s wild.”

“Right? God I’d hate to be her.”

Theo’s mind groped. He knew better than to cosign on the sentiment, pondered a better reply. But now Aja was sort of straddling one of his legs, her locks brushing his shoulders, a black bra peeking out of her collar and her skirt bunched up beneath her ass, which still regularly struck him as extraordinary. She moved the afghan gingerly to the coffee table, and that was the sign. His mind stilled.

He’d lived with women all his life—a mother and twin sisters, three chaotic but familiar presences; a fastidious housemate in his senior year of college; the Manhattan trust-funders who’d graciously offered up a glorified closet into which his bed just barely fit during the lean year before he’d learned to handle his ephemeral start-up salary; the Park Slope screenwriter who’d traded him the master suite for significantly more rent during the more bountiful Goldman Sachs years that followed; Heaven, in the moments after she emerged from their shared Williamsburg bathroom and before she flounced out the door to one of her shows—and the well-known generalities held. The main things were to (1) mind his business, and (2) invest in a TubShroom.

But then there was living with a woman, a different animal entirely, complicated further by the fact of her name all by itself on the lease. It began and ended with the strange humiliation of handing her a check for a nominal amount on the final day of each month. (And why a check, when everything else—down to splitting the bill at meals on Dutch days—was digital? “It’s our business,” Aja always said with a wink, tucking the limp slip of paper into her wallet. “Venmo doesn’t need to know how much this pussy is worth.”)

And in between were the other surprises. The sudden disappearance of most of his books, which turned up eventually in a plastic storage crate at the back of the coat closet, the bookshelves apparently reserved for framed photos and a curated handful of Aja’s books of equal shape and size. His offer to bring home takeout when she seemed stressed at work, only to be told that it actually relaxed her to cook elaborate meals. The deep offense she took when he fell a step behind in the saga of her friends’ relationship statuses. Her little bolts of bawdiness (Venmo!), after all the work he’d done to sanitize his vocabulary.

And then it would be the end of the month again, and there he’d sit at the teak table she owned, scrawling out another check in his shitty handwriting. The amount, which they’d settled on when he’d received his first bleak contractor’s paycheck, embarrassed him. Worse, she’d given him May free, before the job materialized, and never let him square up for it.

He’d once watched his father, then a gig bassist, empty his pockets of cash tips, a dirty little pile building on the counter. His mother’s mouth set in a grim line as she watched, counting silently, and then scooped the ones and fives into the rent envelope along with the hundreds she’d already taken out of the ATM.

Aja didn’t want to hear about that any more than he wanted to talk about it. “I’m just glad you’re here,” she’d say, et cetera. He tried different ways of making up for it, but all their favorite takeout places were cheap, and she’d never eat that many wings anyway.

“Whoops.” Aja giggled, wriggling back into her tights. “We should have hung a sock on the door or something, just in case.”

“Ha,” said Theo. “Cy probably doesn’t even go on for another two hours. Those shows go late.”

“Better save up my energy for Tuesday, then.” Aja started for the bedroom, then paused at the door and pointed toward the bathroom. “Could you, um”—his eyes followed her gesture and he understood—“wipe down the sink again, and then finish whatever you were watching?” She gave a sheepish little smile, then disappeared into the bedroom and shut the door.

Well. He would do it, but he would finish his Black Mirror episode first. Didn’t matter that it was a rewatch. He waited till Aja seemed to quit stirring behind the bedroom door, then resumed the episode.

As an afterthought, he went to the (spotless!) kitchen and found a Dogfish Head in the fridge. It was, after all, a Saturday night.

In the morning, he left Aja reading in bed and Cy snoring lightly in the living room and exited the apartment, taking the stairs instead of the elevator. In the lobby, he ran in place until he thought he could deal with the November cold sans outerwear, then pushed through the revolving door and began jogging the length of U Street. He took the long way around to Meridian Hill Park and then jogged the perimeter, glaring at his own 15th Street office building from across the street. God, what a depressing place, particularly on a Sunday morning, a few North Face–clad drones beeping in to close out the week that had just ended, or jump-start the one coming up. Thirsty asses.

Not that he didn’t relate—in his Goldman Sachs days, he’d spent more Sundays that way than not, hunched at his desk. Relegated to following Cowboys games by refreshing the stats on the team’s website rather than risk streaming anything on company computers. In a way, it was better now. At least no one here expected him to spend weekends in his sad little hole of a government office. Certainly they weren’t paying him to do so; and even if he’d wanted to, they made it insultingly difficult for a lowly contractor to gain access outside of business hours. Even his access badge was a different color, the photo horizontal instead of vertical.

He stopped at Starbucks for bagels and coffees, remembering at the last moment to get extras for Cy, and then walked home, the cold catching up to him. Before the elevator door opened, from all the way down the hall, he heard familiar voices. He had to set the Starbucks on the floor to unlock the apartment.

In the kitchen, Aja and Cy, their heads thrown back in loud laughter. She at the stove, pushing something savory around in the big skillet; he on a barstool in a bathrobe, one long leg draped over the other. “Theo!” they said in unison as he entered, and Aja dropped the spatula, came forth with a performative kiss. Along the countertop: the open-mouthed waffle iron, batter drooling from its edges; a plate of waffles punctuated with chocolate chips; another plate of fat chicken sausages split longways; a half-empty bottle of brut rosé, a nearly full bottle of orange juice. A mimosa at Aja’s elbow and another on the counter in front of Cy.

For reasons unclear, irritation surged in Theo’s throat. “Wow,” he said. “Everybody’s up already!”

Cy rose and pulled a third champagne flute from an overhead cabinet. “I’m getting to know my hostess!” he said. “Also, last night’s crowd sucked and I was in early.”

Early still had to mean after 2:00 a.m., when Theo had finally gone to bed after a while spent tooling around on ZipRecruiter. But all right; Cy was grown.

“Here,” said Cy. The mimosa he handed Theo was no more than 10 percent OJ, and it dissolved some of Theo’s unexplained annoyance. The cousins clinked glasses, like in their roommate days.

“Tell him what happened last night,” Aja prompted Cy. “The money thing.” She tipped the skillet and poured sautéed mushrooms onto a clean plate, pan sauce over top. Drippings of butter and herbs landed on the counter and there they remained as she arranged servings of each food on yet another plate.

“Oh, that,” said Cy, waving a hand. “Typical group-project bullshit. There was this flimsy little ensemble number in the middle and two of the girls didn’t know it.”

“And you have to know it,” Aja interjected. “It’s a whole political, contentious thing.”

“Which they knew,” continued Cy. “Posted everywhere backstage. They dock you if you’re late, they dock you if you don’t know your lip sync, they dock you the most if you fuck up the group number. Which these two knew.”

“But then!” said Aja, and set the plate before Cy. She’d added whipped cream to the waffles and a little sprig of fresh parsley on the side. Theo eyed it.

“But then, this place, they also pool tips,” said Cy. “And one of the girls, the ones who didn’t know the number, is tight with the manager, and got him to divide what was left after docking those two.”

“Such bullshit,” said Aja. “Basically, they ended up dividing the penalty.”

Theo’s mind whirled. Aja had settled on the other barstool, opposite Cy, so Theo went to the cabinet to seek out his own plate.

“Let me know if you need more whipped cream,” said Aja, leaning halfway over the counter to watch Cy cut into a waffle. “If I can’t be as thin as you, then I need you to be as fat as me.”

Laughter from both. Theo shut one cabinet and opened another. “Are we out of plates?”

“And then it’s so annoying that you have to go back tonight,” said Aja.

“But on the bright side,” said Cy, spearing a minuscule bite of waffle with his fork, “where else would I wear that other basic-ass, low-rent Disney princess dress I brought to town? What a waste that would be.”

“At least there’s Maisie’s,” said Aja.

“Whole different thing, thank God.” Cy nibbled and swallowed dramatically. “I’ve done Maisie’s twice before—night and day. Actual art appreciators in the audience. Worthwhile tips. And that was before I even”—here he pantomimed creating and completing some craft with his hands—“had Heaven together. You know?”

“That’s so great,” said Aja. “So great. I can’t wait.”

“So glad you’re coming,” said Cy, and reached across the tabletop to clasp her hand in his.

“Gotta shower,” Theo said, and headed that way, tucking the Starbucks bag—all three bagels still warm inside—under his arm.

He understood, of course, what Aja imagined. What anyone would imagine, clouded with Paris Is Burning references and encountering Cy’s waifish thinness, the shoelace in his hair. Cishet persecution and starving artistry. Lazy coworkers stealing the communal tips when poor Cy had already had to pay out of pocket for the bus ride down.

How very fucking annoying. Did you have to look out for him a lot as a kid? she’d asked once, when Cy was still just a vision from YouTube.

And, well, sure he had. Boys in the nineties, what could you expect. At summer camp, willowy Cy, taller than everyone else their age, would sign up for dance and fiber arts and spend free periods on the fringes of deep fields, talking to birds. He’d embodied plenty of the stereotypes, and Theo remembered that sometimes some shoving had been necessary to shut some bully up.

(And, yes, he’d omitted the occasional salient detail, the times he himself had been the instigator or had waited perhaps longer than he should have to intervene in the face of a threat. No one was perfect at that age, were they? Not even Cy himself, with his short fuse and surprisingly fierce right hook.)

But between their mothers—Cy’s the sensible elder sister and Theo’s the younger and flightier—Cy’s had been better suited to raise the son she had. Aunt Cassandra and her husband, the towering Dane, had chosen Quaker schools with progressive values and rich arts programs, paid for outside dance lessons, all that shit. Whereas Theo had once, due to his mother’s fumbling a registration deadline, spent a whole semester in the wrong public school; not the rigorous one he’d tested into, but the one rumored to be for—well, you couldn’t even say the word anymore. That chunk of wasted time, his first introduction to the tragedy of a false start.

So, whatever the fuck. It was sad, of course, losing a few bucks to a couple of flakes. If the loss cut too deeply into Cy’s bus fare, maybe Miss Waffles-and-Moneybags would spot him the difference.

“Thought you weren’t coming today!” said the guy at the wings place.

“You thought wrong,” said Theo. “We play the Vikes in ten minutes.”

“Cutting it close!” said the guy. “Let me guess: your lady.”

“Ha,” said Theo. He wondered whether his domestication gave off an actual scent. Maybe the brain-cell-killing artificial lavender of Fabuloso, at least a cup of which he’d had to use on the war-ravaged kitchen countertops.

“Here,” said the guy, and dumped in an extra dozen before sealing the Styrofoam container. Half buffalo and half rosemary. For the first time all day, Theo’s mood brightened.

Some three hours later, though, he was grouchy again. A loss—especially one that narrow, four freaking points, and especially on home soil—really was a shitty way to launch another grinding DC workweek. It was true what a buddy of his had once said: You didn’t need to lay down money to feel you had skin in the game. The highs were there either way. Though so were the lows, of course.

Cy had stayed out someplace overnight, and Aja slept in and teleworked on Mondays, so Theo drank his reheated day-old coffee in the kitchen in peace before bundling up for his commute. Unlike at Goldman, where everyone had found hyperpromptness exhilarating, coked up on their own high standards, here there was no reason whatsoever to clock in before 8:30.

If one had a reason to be grateful for this job beyond the excruciatingly obvious, it was that one could finish all one’s assignments within the first half of the day and reserve the rest for nobler pursuits. After lunch, Theo rewatched several key segments of the previous night’s game, pinpointing exactly where the Cowboys had gone wrong. Turnovers right out of the gate, and then a terrible onside kick attempt in the third quarter.

His hand twitched toward his phone. But instead of navigating to a fantasy roundup or some other forbidden website, he texted Brandon, of Brandon and Tiffany, consulting-firm power couple: Where for drinks tomorrow?

While he awaited Brandon’s reply—to hear Brandon tell it, life as a manager was both a sprint and a marathon: constantly busy, sheer productivity its own metric—he scrolled the internet, adding to his research file on both firms. Either would represent so drastic an improvement that it was hard to rank them. Though there was the fact that the junior associates at Brandon’s firm tended to be a year or so older than those at Tiffany’s—at least according to the application-gaming message boards. But how much did that really matter now? He, king of the false starts, would be older than every underling at either place, regardless.

He followed up with a second text: Aja and my treat.

Someone poked their head into his office—they didn’t knock around here—and asked him to make copies of a stack of documents. Menial but time sensitive, the worst combination. He got up and did it. By the time he came back, Brandon had replied: No, it’s our turn to treat this time, it read, and offered the name of a bar.

To pass the day’s final hour, Theo googled his father’s name, as he did from time to time, following it up with words that seemed pertinent. Bass. Jazz. Music. Each returned results that skirted his intentions. A random bassist—not his father, but a man around the age he’d be now—giving an informal interview in which he mentioned contemporaries he admired, among them Theo’s father. A middle-school jazz band butchering a piece of music Theo had determined was one of his father’s notable compositions. Et cetera.

Frustrated, he googled Cy’s name next, and of course the results were in the hundreds of thousands. Most of it, of course, was garbage, bad cell-phone videos of trashy lip-sync gigs like the previous night’s, though Heaven herself was luminous and, judging by the cheers that rendered her act inaudible, pleasing to her audience. This, for the record, was the reason Theo had never managed to get to one of Heaven’s shows, despite Cy’s periodic invitations. What was there to like about spending the evening being trampled by a crush of rabid fans? Each crowd was bawdier and more boisterous than the last.

Without meaning to, Theo finished the day that way, following one link to the next. Pop song after pop song. Wig after wig. Smoothly waved chestnut, racially ambiguous blond, teased-out Diana Ross Afro. Once or twice, Theo startled at how Heaven resembled a young Aunt Cassandra, though differently proportioned—and aside from the glittery bluish glow, of course.

Aja and Cy were at the teak table. “Theo!” they said in unison, again, as he entered.

Aja reached for his hand. “Look!”

They’d pulled out an old photo album, an unsolicited gift from Theo’s mom, which they must have found tucked away in the coat closet. Theo sat obligingly and let Aja show him a photo of himself and his cousin at around five years old. Two little reeds with arms slung around each other, one a sunbaked brown and one less so. Atlantic City, read someone’s handwriting in the corner.

“Soooo cute,” cooed Aja.

“I sure was,” said Cy. “Kidding!”

“Well, you were,” said Aja.

“But there’s a family secret,” said Cy, “which is that basically one person in each generation gets the looks, and then everyone else is just an also-ran. Anyone else who wants them has to paint them on.”

He took the book and flipped back several pages to an older photo: their shared grandparents at their peak. Aja leaned in and drew in her breath. “Gorgeous.”

“Ha,” said Theo. “So, yeah. It was our grandfather, and then here’s his dead ringer, plus some Denmark.”

“Yeah, but no,” said Cy, furrowing his brow. “Mom and I look like Granddad. But the beauté originale was Grandma Opal.” He turned to another page, later, their by-then-widowed grandmother on the Boardwalk holding some infant sibling or cousin of theirs.

Aja leaned in again, and gasped again. “Oh my God, weird,” she said. “Theo, you look—”

“Just like her?” supplied Cy, triumphant. He framed a portion of the photo with his hands. “The little chin dimple?”

Aja reached up and ran a hand across Theo’s chin.

“I always called it the Opal cleft,” said Cy. “Theo and his mom have it, and no one else. I have this pointy shit! That’s why I’ve spent a fortune on little teeny-weeny contouring brushes. I draw one on myself for worthwhile gigs.”

Theo leaned in. It was surreal, hearing himself described this way to Aja, who’d surely looked through these photos with him before, though probably not this closely. And to have his own vague misinterpretations so summarily dispelled. Sure, he knew about the family secret, but it had never occurred to him it wasn’t a glamorization of the good looks of his late grandfather, who’d died young and handsome. And the so-called Opal cleft—he’d never given that any thought at all, more concerned with his relief at what his mother hadn’t passed down.

“Speaking of which,” said Cy, rising, “anyone need to get into the bathroom anytime soon?”

The guy at the wings place had his back to the door and sat alternating his gaze between the old television mounted on the wall and the display on his phone. Theo recognized the orange and green of the DraftKings website. “Hey,” he said. “Picking up an online order.”

“Oh—hey, man.” The guy turned and started assembling Theo’s order. “Who’s the naked ones for?”

“Huh?” said Theo, distracted. On the old TV, a panel of commentators sat dissecting the 49ers’s first string, running scenarios for the evening’s home game.

“The plain wings,” said the guy. “I never seen you get plain ones before.”

“Oh, yeah,” said Theo. “My lady eats them without sauce.” He shrugged. “She doesn’t like getting her hands dirty.”

“They be making us do things,” said the guy, returning the shrug.

Indeed. Aja almost never watched football with him; on Monday nights, she absented herself to meet up with friends or lingered at work. Her offer to join had come as a surprise—a little dose of happy-couple theater for their houseguest’s benefit?

The guy sealed the Styrofoam container with Aja’s naked wings and heaped in another dozen with Theo’s, spooning barbecue sauce over the extras. “Oh well. More for you.”

The guy’s phone dinged: A DraftKings notification? Theo wanted to ask whether he had money on the 49ers, or maybe a fantasy team poised to advance pending the night’s outcome—but look at the time, only ten minutes till kickoff. Instead, he handed over his twenties and took the bags in silence, dawdling only briefly before the TV.

“Ugh, this bathroom,” said Aja the moment Theo walked in.

Theo set the wings on the table and peered in. Again, Cy had left behind a storm of cosmetical offal, a sink full of stubble, a sheen of blue over everything. “I’ll get it after the game,” said Theo. He set the takeout bags on the countertop and reached into the fridge for a Dogfish Head.

Aja watched him crack the bottle open. “Could you, um?”

“Could I what?” He sank onto the couch, remote in hand, irritation surging. “Babe, I’ll get it after. Or, better yet—Cy’s grown. Let him handle it when he gets in.”

On-screen, the 49ers were jogging onto the field, a few minutes behind schedule. Thank God. But then Aja wandered into his sight line, arms folded. “He’s company,” she said tightly.

“He’s family. I cleaned up after him once already. Can you sit, please? Can I—we—watch the game?”

Aja perched on the arm of the sofa. “Can I ask you something?”

Theo sighed and muted the television.

“Back when you lived together,” said Aja.

A vision of the Williamsburg apartment snapped into Theo’s mind: Spartan, serviceable furniture dotting the living room; Cy’s dead houseplant and Theo’s long-empty fish tank on the windowsill; bare kitchen cabinets; a counter perpetually covered in takeout containers. A faint dusting of shimmer that thickened as you approached the shared bathroom.

“Toward the end, I mean,” continued Aja. “Didn’t Cy have to spot you once? Rent, utilities?”

Theo’s jaw tightened. “You know he did,” he said. It was one of the things they’d talked about once so that they would never have to again. His lowest of low points. With his final Goldman paycheck already spent, the Cowboys got knocked out before the conference championship. His phone, exploding with notifications from various betting sites, a string of bad decisions coming home to roost. Debts piling higher than the dishes in the kitchen sink.

And Cy, affable as always, no detectable judgment in his kohl-ringed gray eyes as he tapped the numbers into his cell-phone calculator, then sent over a sum to cover the bulk of Theo’s share of the bills.

Not once, in fact, but twice. Which of course Aja knew.

“I actually find it bewildering,” she was saying. “That you don’t feel more—”

What was the word on her tongue? Appreciative, indebted, maybe pathetic? Theo sat up straight and drummed his fingertips on the remote to keep from hurling it at a wall.

“That you aren’t more supportive,” she finished finally. “If it were my cousin? I’d be at all his shows, even the bad ones.”

“We’re going tomorrow, right after drinks with Brandon and Tiffany.”

Aja’s eyes narrowed. “Right after what now?”

Another source of bewilderment: that two people could share twelve hundred square feet of space and still bungle a simple transfer of information. Aja’s face registered zero recognition as Theo explained the plan, Brandon and Tiffany’s new managerial statuses, the bar Brandon had proposed.

“You did not tell me,” she said when he finished.

“Absolutely, I told you,” Theo repeated, slapping the back of one hand into the palm of the other for emphasis.

“I would have said no. I hate watching you network with friends.”

“It’s not networking—it’s just drinks. You would have said no to, like, ninety minutes of sitting at a bar two blocks away?”

“If you had actually asked, I probably would have consideredit. But you’re springing it on me at the last minute, and it’s on the same night as Cy’s show. And it’s definitely networking.”

Feeling ridiculous as he did it, Theo grabbed for his phone and searched his text history, trying different word combinations. Drinks with Brandon. Drinks with Tiffany. Drinks on Tuesday. Nothing, nothing, nothing. What the fuck. “We talked about it,” he said, his voice thin. “Like yesterday.”

Aja laughed dryly. “Yesterday? While you were slamming around the house being rude to your cousin and then going into a football coma?”

“I wasn’t rude!”

Aja got to her feet and did a hulking imitation. “No one’s paying attention to me, wahh. I’m gonna go eat bagels in the bathroom! Meanwhile Cy’s trying to tell us about losing half a night’s pay—”

“Half a night’s pay,” repeated Theo, the words cutting at the insides of his mouth. He jabbed at the remote and sound burst from the TV. “You know what, forget it. Forget it. I’ll just go by myself.”

Aja stared, stunned, and finally stalked off toward the bedroom. “Great,” she called over her shoulder. “Have fun not networking.”

She was out first the next morning, per Tuesday’s norm, and Cy didn’t stir on the sofa when Theo reheated another deferred Starbucks cup.

The bar Brandon had chosen was wood-paneled, with rich-looking espresso chairs. The sort of place the Goldman bros would have chosen, laughing if you looked agog upon entry. Theo supposed that was Brandon and Tiffany now: effortlessly resourced, no longer impressed by places with two-for-one rail specials.

They did, to their credit, limit themselves to asking once each—where was Aja, anyway? Brandon asked it as they were seated, before he’d even removed his moneyed leather coat; and then, while Brandon was in the restroom, Tiffany leaned close, peering over her Warby Parkers, and asked again, as if the answer might change.

That thing couples did as they situated themselves further into couple-dom. Losing their ability to socialize in odd numbers, unsure how to physically orient themselves at a four-top, even how to order drinks. After interrupting Theo twice, Brandon finally grinned apologetically at the server and said they’d have a round of mezcal mojitos.

Their new jobs? Wonderful, wonderful! Everything falling into place, their leadership skills really progressing, even the rigorous schedule an easy adjustment since they were both on it. And it made the wedding planning so much more efficient, ironically, if he knew what they—well, of course he’d let them know when he was ready for the inside tip on wedding planning, right?

But, yes, the jobs, everything fantastic. And his? Just great also, nice to have more of a work-life balance for the moment after Goldman, though he was beginning to think maybe it was time for—

Here were the drinks. God it was nice to go crazy and have a sugary mixed drink on a weeknight, responsible old grown-person wine got so boring, though of course it made mornings easier; could he believe there were still people his age who did this every night and kept their jobs?

During a lull, peering into the phone in his lap, Theo found he had a text from Aja: Hope you’re having fun drinking casually with your friends. I’m heading to Maisie’s early. Stopping at the ATM. Don’t forget cash for tips.

He resisted the urge to ask just how well she planned to tip. His own perception of Cy’s charlatanism aside, it was her money to spend. None of his business.

Though maybe after Cy had left, safely on a bus back to Williamsburg, Theo might pose the question in some unassholish way, leading Aja to draw her own conclusions. How exactly did she think Cy was making ends meet, lo these six roommateless months, in gentrified Brooklyn, on a few nights per week of pooled tips? The same simple money-earned, money-spent hamster wheel Aja herself had been on throughout adulthood, or was there a more realistic explanation? An indulgent mother and a towering, deep-pocketed father, perhaps? Cy could do whatever he wanted and fall up. Not everyone was so lucky. Some people had to try other things.

Theo returned his attention to the table and managed to reach the bottom of his cloyingly sweet drink, admired Tiffany’s ring once more, offered again (unsuccessfully) to pay the check.

And when, just before they reached the door, Tiffany doubled back to hit the restroom, he found the balls to touch Brandon’s arm and say: “You know, if either of you has an opening anytime soon, I’d love you to keep me in mind.”

In another chapter, this sort of thing had been so easy for Theo. Evidently that chapter had closed, giving way to this awkward and domesticated DC chapter. Back in the empty apartment, he gave the kitchen another thorough cleaning, until he reached the bottom of the tub of Lysol wipes. Just to settle his nerves.

Maisie’s sat tucked just off the main strip, behind a row of more conventional and brightly lit gay bars meant to invite foot traffic. You had to know it was there, which until this weekend Theo had not. He paid the cover, had his hand stamped, squeezed into an open sliver of space at the bar, searched the crowd until he found Aja and, by her side, her dick-grazing friend Brielle. Both laughing and wearing low-hanging earrings. Their purses full, presumably, of law-firm cash.

Well. He turned and ordered a drink, something simple and cheap, pleased to watch the bartender’s heavy-handed pour. The crowd here was mostly male, and nothing like the screaming legions he’d seen on YouTube. Jazz fans, he supposed. Professional dress, neat haircuts.

He claimed a seat at the bar and checked his phone. An email from Brandon, brief and to-the-point:

Really enjoyed catching up with you, man. Shared what you said with Tiff and we’ll both keep it in mind. We think you’ll find a good fit soon. Wanted to say that we think it’s good you’re taking a break from some of that for now. Wouldn’t want to see you burn out again so soon, or get caught up in anything else. Just enjoy the extra time with Aja.

Theo took a sip of his drink and swallowed. Returned his phone to his pocket, just as the lights dimmed.

A spotlight swung over a stage at the back of the room, a standing microphone stretched to maximum height. Music started up, prerecorded but voluptuous in the high-end speakers, and touched off a scattering of whistles throughout the room. A bass line, the skitter of a hi-hat, a crescendo of piano melody.

Then Heaven appeared onstage, first one endless leg and then the other, the blue dermal shimmer toned down to emphasize a glittering blue gown; and there indeed was the painted-on cleft in her chin, though nothing looked painted at this distance and in this light. In her shoes, remarkable pale gray platforms with sequins down each stiletto heel, she must have stood at least six-foot-seven; somehow, though, she was lithe and glittering, feline, not the least bit gawky. The room around her stilled and Theo felt his mind quiet along with it, all thoughts of the night’s failures receding.

As many dozens of metamorphoses as he’d seen, as many times as he’d watched Heaven emerge from the bathroom, a sky-colored spectacle with a blizzard of cosmetics in her wake, somehow he hadn’t expected what now stood before him. Where in there was his cousin—overtall, underweight Cy, who’d tripped over his own feet as a child? Pampered Cy, whose parents paid his rent? Nowhere to be seen. He stole a glance at Aja and saw her full-bodied gasp, her pretty hands covering her mouth exactly as they had the first time she’d seen a Basquiat up close.

He turned his gaze back to Heaven. He watched her shine a demure smile around the room, seeming to make playful eye contact with every member of the audience all at once; and then she began to sing, a contralto like a cloud floating majestically past, and you had to admit maybe there really was something to this whole thing.

Anna Schuleit Haber’s work has appeared in public and institutional settings, in galleries, museums, and theaters. She studied painting and art history at RISD, creative writing at Dartmouth, and was named a MacArthur Fellow for works of “conceptual clarity, compassion, and beauty.” She is currently working on a series of...