Image

You should really subscribe now!

Or login if you already have a subscription.

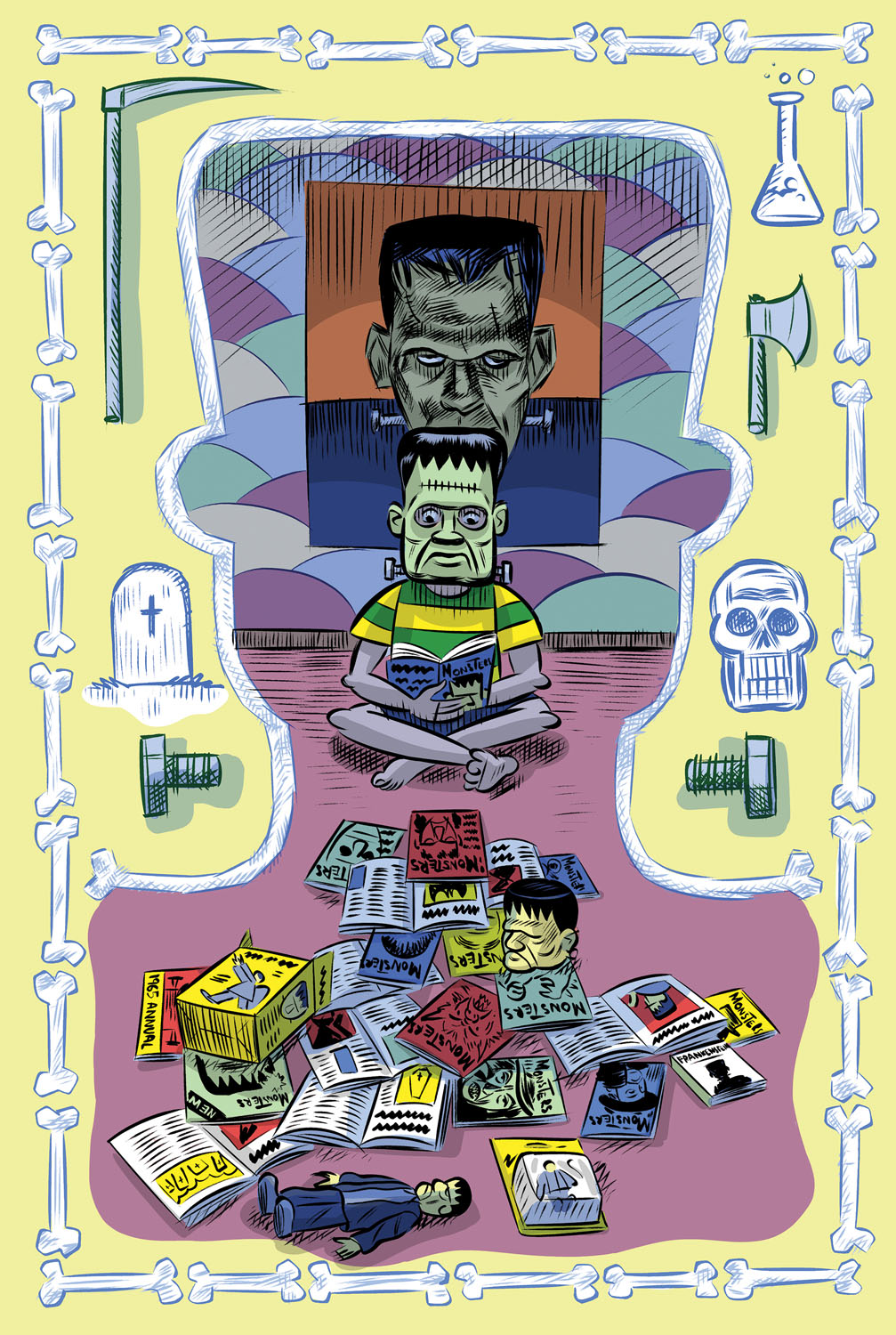

Michael D. Kennedy’s debut graphic novel is Milk White Steed (Drawn and Quarterly, 2025). He is a cartoonist and illustrator from the West Midlands, UK.