Speak (Correctly), Memory!

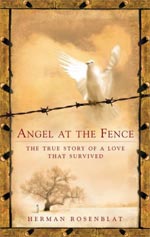

This spring, a colleague at the Christian Science Monitor and I collaborated on a piece that ran under the headline: “Memoirs: whose truth — and does it matter?” The context, as I wrote at the time, was a “string of high-profile scandals,” from the James Frey debacle to the revelation that Mischa Defonseca, the author of a fantastical memoir of the Holocaust—which suggested Defonseca had been rescued by a pack of wild animals—”lived in Brussels during World War II, is not Jewish, and was not raised by wolves.”

Teresa Méndez and I split the reporting, mostly because there was so much ground to cover: presumably, editors, writers, and publishers would have a wide range of viewpoints on the necessity of truthiness in modern memoir. We talked to dozens; many were happy to chat, and only a few demurred. And for the most part, almost everyone—save Jack Shafer, Slate’s formidable media critic, who had come out loudly against David Sedaris in a 2007 column—was in agreement: totally false was bad, but a little slippage was acceptable. As Sedaris told me, speaking from his home in England, “I guess I’ve always thought that if 97 percent of the story is true, then that’s an acceptable formula. Put it on a scale. Is it 97 percent pure?”

How much is too much? Do you care if a memoir isn’t 99.9 percent true? And wherein lies the dividing line between memoir and fiction?