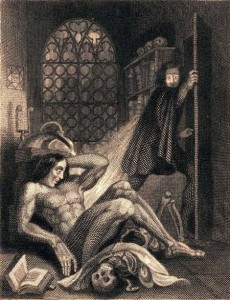

A Modern Prometheus

Summer holidays are good for many things: sleeping in, time in the sun, and, for some people, writing. Nearly 200 years ago, Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley used her summer travels to Switzerland to develop the idea that eventually became Frankenstein.

Shelley imagined her character as the ultimate incarnation of the medically unbelievable, and during the early days of the 19th and even 20th centuries, he probably was. However, science and technology are anything but static, and in 2009 when it comes to jaw-dropping tales of medicine, I can’t help but think that sometimes truth is stranger than fiction.

During my first week as the medical student on the gynecology-oncology service, I wasn’t supposed to be daydreaming in the OR. Most of the time, the medical student experience involves standing, for hours at a time, cutting sutures, suctioning blood and who-knows-what-else, and always retracting, holding the instruments that keep organs and tissue out of the way so the operating surgeons can see what they are doing. It’s exhausting, so on this particular day, I couldn’t believe my good fortune when I was offered a chair. “Sit here,” my resident told me. “There won’t be anything for you to do since they’re using the robot.”

“The robot?” I thought. “Does the patient know about this?” When the surgery began, my right-brain couldn’t banish the thought of Frankenstein, even as my left brain leaned forward for a better view. Laparoscopic surgery—operating through tiny incisions in the body, with the help of a fiber optic camera that displays the view from within—has become more and more common as medical technology has become more sophisticated. Twenty years ago, removing a gallbladder left a ten inch scar. During my surgery rotation, I scrubbed in on just such a cholecystectomy, and it left the patient with just a pair of one centimeter incisions on her abdomen and a scar buried in her belly button. So I was used to surgery that involved staring at a TV screen and manipulating very tiny and very expensive gadgets. Yet even with laparoscopy, a real surgeon still has to manipulate the tools.

Then I met the Da Vinci surgical robot, the next iteration of surgical innovation and perhaps a marker for the future of medicine. The problem with laparoscopy is that it forces surgeons to operate in 2-D, confined to the view on the screen. When the Da Vinci is used to operate, the surgeon controls the robot, and the robot controls all of the surgical tools inside of the patient. To operate the robot (and the second generation Da Vinci at our hospital has four arms), the surgeon sits in the corner of the OR, staring through a console that uses the video from the robot cameras to create a 3-D image of the view from inside the patient. Each of the arms moves by flipping a toggle, manipulating hand grips, or pushing pedals with one’s feet. I’m not sure who came up with the concept of the surgical robot, but I suspect it was someone who played a lot of video games as a child (and maybe as an adult…) The best surgeons can precisely control the smallest movements of their fingers, but the robot bests even the most skilled humans, because in translating motion from the console to the mechanical arms, even the most minute of tremors are eliminated.

Watching this for the first time, it was hard not to feel that I’d stepped into an alternate reality. There was the patient, draped like usual, but instead of being surrounded by the surgical team, she was enveloped by the metal arms of a multi-million-dollar robot that vaguely resembled a giant octopus. The anesthesiologist was the only person anywhere near the patient, because the rest of the surgical team was huddled around the screens scattered throughout the OR, eyes darting from the view inside the patient’s abdomen to the robot’s console in the corner, where our attending was pulling on levers, moving his feet, and pressing his face into the eyepieces with all the enthusiasm of the most devoted video gamer. Except he was a surgeon. In the OR. In the midst of dissecting out metastasized ovarian cancer from the surface of a patient’s abdominal blood vessels.

When he stepped away from the console to answer a page, I took the opportunity to sneak a view through the eyepieces. I held my breath as I stared at the view through the console—an intact abdominal cavity from the inside, complete with peristalsing intestines, pulsing aorta, and glistening strands of yellowish abdominal fat.

In the nearly two centuries since Mary Shelley used a fictional creation to wonder about the limits of human technology, the challenges posed by what we can do versus what we should do have only become more complicated. Advances in science and their corresponding applications to medical practice have created ethical quandaries that would have been considered science fiction in the not-so-distant past. At the same time, sometimes technology can also be used to great benefit. As I watched the arms of the Da Vinci twist and turn, seemingly in control of the entire procedure, I couldn’t shake the thought that somehow it just didn’t seem normal for a four-hour surgery to proceed without the surgeon ever touching the patient.

I went on rounds later in the day, and visited the patient. I was anticipating her post-op state to be as bad as that of ovarian cancer patients who have undergone traditional open laparotomies, in which their abdomen is incised from pubic bones to sternum.

“How are you doing?” I asked.

“Oh I’m just fine!” she said, almost cheerfully, alert and clear-eyed from her bed. “How are you?”

I have to conclude that whether or not something is “normal” isn’t the best test of technology. If technology can sometimes be monstrous, it can also at times be magical. Remember: Frankenstein was the scientist, not the monster.