Due North

“Walkers are ‘practitioners of the city,’ for the city is made to be walked, [Michel de Certeau] wrote. A city is a language, a repository of possibilities, and walking is the act of speaking that language, of selecting from those possibilities.” —Rebecca Solnit

I’m an island boy and wear that designation with pride, and so I decided that, despite New Yorkers’ cautions to the contrary, I would not live in their city as some worker bee too busy to make contact with passersby. Strangers might stamp me as crazy, but I planned to talk to them. They would be my skeleton key to the city.

I came to the city—which, for me, meant all five boroughs (yes, even Staten Island)—after Hurricane Katrina flicked me north. And I intended to immerse myself in its rich, colorful cultural life by spending a lot of time walking; after all, that’s how I got to know the vibrant streets of Kingston, Jamaica, where I grew up, and New Orleans, where I spent almost a decade. “You can tour the world at the cost of a monthly subway pass,” I once heard a New Yorker boast. Indeed, tour I would, but this meant getting off at stations almost at random and walking, lots of walking and talking, to observe, to absorb, to understand.

For the myth of the place, the promise of New York, was that, with a dose of sparkling luck, you could join its throngs and have their fascinating lives broaden and deepen yours. “If you’re bored it’s because you’re on the wrong block,” said my indefatigable friend Maxine, who lived a few blocks from the never dim (though often dull) Times Square. I could hop on a train to Jackson Heights in Queens and walk along sidewalks made resplendent by Indians, Bangladeshis, Tibetans, and Nepalis who shop and sell side by side; and, night owl that I am, I could return at 2:00 a.m. for Nepalese food, eating yak while chatting away. This was the city of high social and cultural aspirations and achievements—the “city of opportunity”—where, I was led to believe, cosmopolitanism won the day. I had every intention, then, to join its pageant of walkers.

I arrived in New York in October 2005 and immediately began walking all over the city, exploring for hours at a time. As I traversed its landscape, I discovered a topography of social conditions. Some days, I would linger on Thirty-Fourth Street among the glamorous workers of Midtown Manhattan rushing to and from their high-rise buildings—in swift pursuit of their ambitions, I’d assumed. I’d watch them zigzag around and dart past the enthusiastic tourists filing into the Empire State Building, that colossus rising majestically above as a beacon of hope and symbol of American derring-do.

Then I’d stride northward, eager to explore Whitman’s “Numberless crowded streets – high growths of iron, slender, strong, light, splendidly uprising toward clear skies.” A little over two hours later, I would end up in Harlem at the courtyard of a housing project on 125th Street, where residents lounged on benches and welcomed each other with cheerful banter. They also welcomed me, and I sat beside them, took one of the kiddie’s box drinks they offered, and enjoyed their jovial talk in that relaxed, open space in Harlem far removed from the hurried dynamism of Midtown.

But as I’ve circulated through New York’s streets, nothing reveals the city’s opposites in stark juxtaposition like the walk from the Upper East Side to the South Bronx, two neighborhoods separated by a brisk ninety-minute walk, or a quick twelve-minute subway ride. I’d call them neighbors were it not so clear that they occupy such distinctly different worlds. To walk the streets from one to the other, as I often do, is to bear witness to a landscape of asymmetry. The city that comes into view is one of uneven terrain, vistas of opportunity alongside pockets of deep poverty too often lost in the periphery.

In early 2006, almost six months after moving to the city, I was hobbled from roaming around because of a botched surgery on my right knee. A few months later, I switched hospitals to the Hospital for Special Surgery, located on the Upper East Side, where I eventually underwent two more surgeries to get back to walking the streets without chronic pain. As a result of the operations and follow-up physical therapy, the Upper East Side became a regular destination. I spent a lot of time watching people go about their lives, many of whom were middle- and working-class people employed in hospitals, museums, universities, hotels, and elsewhere on the Upper East Side. Plentiful as these workers were, they didn’t define the neighborhood—at least, not in a way that forcefully impresses itself upon the mind when you think of the Upper East Side. No, the population that embosses its mark on the neighborhood is the wealthy—the extraordinarily wealthy, to be precise.

The Upper East Side houses one of the richest zip codes in the US. This wealth touches almost everything in its vicinity. Many of the less-flush people I met going about their days worked at institutions that were among the world’s finest—the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, Hospital for Special Surgery—and that were easy access for their upper-class neighbors. In addition to stellar medical care and world-class museums, I’d walk past some of the city’s best private schools, public libraries abuzz with parents and nannies—many of whom were foreigners—playing with children, and music schools with eager and not-so-eager kids developing their skills. Here was a neighborhood stocked with the resources for worldly success.

Walking through that part of the Upper East Side was not unlike a jaunt in a museum. On Park or Fifth Avenue, for example, one could walk for hours and admire magnificent buildings fronted by well-manicured gardens and quiet, clean sidewalks. Serenity suffused the atmosphere. Nothing seemed out of place, and, to my untrained eye, it all looked unspoiled.

There are stunning apartment buildings that look like cathedrals in high heels. Überchic boutiques—throne rooms of specialization meant to cater to people with the most rarefied, and demanding, of tastes—abound. You can pick up scented shoelaces for your teen daughter from a store filled with accessories for tweens, buy a bra for a few hundred dollars from an Italian lingerie store, and then drop off your puppy for a spa day, all in under a half hour. And, shhh, the stores were very quiet, I’ll-glare-if-you-speak-loudly quiet. I was often hushed, too, since sticker shock often dumbfounds me. Though, I should confess, something perverse in me wanted me to scream upon entering those hush-up stores.

All around are luxe restaurants with patrons to match, and sophisticated bistros with fresh-looking, pleasant-smelling—oh, those lovely scents!—upscale clientele. And for outdoor relaxation and play, Central Park is a quick stroll away—across the road, even. It’s as if the neighborhood was curated to cater to the needs and pleasures of its wealthy residents. Dig through the historical record and you’ll find that, indeed, starting with Fifth Avenue in the late nineteenth century, later joined in the early twentieth century by Park (formerly Fourth) Avenue, elegance and convenience have characterized the Upper East Side’s moneyed class and its tony residences.

Yet, for all its beauty, the neighborhood today feels like a welcome mat with spikes, or, more aptly, like a museum after closing time. You could stand nearby and look in, but that’s as far as you could go: admiration from a distance. My feet met their limit.

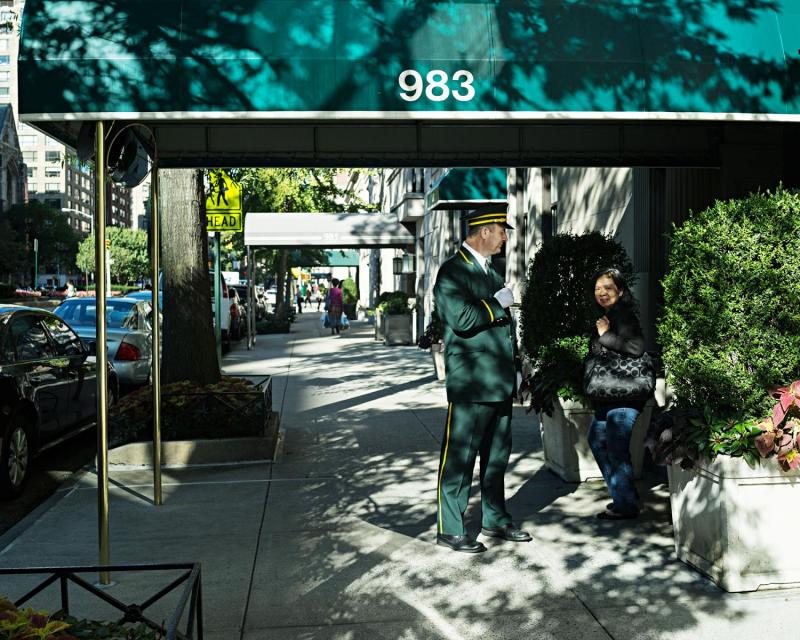

So much of the lives of the very wealthy was a mystery to me, not least because I couldn’t hope to stand and chat with them. The city was this enticing language I was learning, but they were a cipher. They lived, as my friend and walking companion Suketu once put it to me, in vertical gated communities—fortresses within layers of insulation. I’d see them shuttle from cabs or chauffeur-driven cars into their elegant buildings fronted by attentive doormen. Or I’d see them interacting with each other as I strolled past a posh establishment. They were sharply dressed ghosts; I would see them for a brief moment, only for them to quickly disappear into vehicles or buildings as mysteriously as they came.

There was a come-hither-stay-away quality to it all. Apartment lobbies looked inviting, but dapper doormen in their white shirts and black ties stood between you and them. Brownstones were beguiling, but you dared not sit on their steps. And I couldn’t shake the feeling that someone my shade, the color of the neighborhood’s nannies and gardeners and janitors but not their neighbors (at least, none that I saw), was more unwelcome on a stranger’s stoop.

Nor would I ever see people hanging out on their own steps. The beauty of the Upper East Side, the visual allure, had a placidity I felt detached from. There was something disquieting about all that silence. Certainly, one of the joys of living in the city is the wonderful solitude it affords, the option to, as E. B. White memorably put it, opt out and announce, “I did not attend.” The city is a place of escape as much as it’s one of pilgrimage, and, to someone outside of their circle passing through, the affluent inhabitants of the Upper East Side resemble a group who entered a compact to “not attend.” The serenity felt fragile, and I feared that if I did anything that was perceived as a threat to it, no matter how simple—approaching that friendly face to have a chat, leaning over to inhale perfumy flowers—that I would be promptly reminded that I could inhabit those streets only so much.

When I leave the Upper East Side on foot, the streets declare it to me almost immediately. I cross Ninety-Sixth Street—on Park Avenue, say, and the picturesque quickly recedes. Islands of gardens are supplanted by train tracks that tear out of the ground and rise alongside and above houses, transporting streams of Metro-North trains and dispersing noise across the neighborhood. Pristine sidewalks are replaced by dusty ones, and time and again micro-dirt tornadoes, with candy wrappers within, whirl around. And luxury mansions are replaced by tenement-type buildings, row houses, and “superblocks” of housing projects.

And the population becomes increasingly darker. A lot more. And friendlier. A lot more. More Spanish is heard (significantly so), more bodegas are seen on corners, and the hum of the Upper East Side gives way to a skipping, sometimes clamoring, beat. (On weekends with good weather, there are block parties aplenty). You almost begin to wonder—at least, I often do—if East Harlem is the town crier announcing, “Yeah, you’ve left the Upper East Side. The South Bronx is three miles, and an hour’s walk, thataway.”

When I enter the South Bronx my pulse becomes polyrhythmic. And how could it not? Afro-Caribbean music greets me from cars doubling as drive-by sound systems. Strangers greet me with friendly salutations—“Hola, Papi!”; “Whaagwaan, Bredrin!”; “Yes, Rudie!”; “Wassup, G!”; “A’ight. A’ight”—that have the flavor of family nicknames. Chatter intermingled with laughter is ubiquitous. The smells of Jamaican and Mexican and Puerto Rican and Ghanaian food pervade the atmosphere, and my stomach is at odds with my brain. (“Okay, I plan to head in that direction, but that fragrant … Oh wait, is that curry?”)

And, most delightful, people are open and ready to talk: in parks, on playgrounds, on street corners, on their stoops, from their bedrooms (“Hey, what song is that?” I’d think nothing to shout, and a reply would soar over the music through the bedroom window, “Juan Luis Guerra, Papi”). Perhaps, to repurpose the Psalmist’s observation, “deep calls to deep” and the Caribbean in me is simpatico with the sounds and smells of the South Bronx. But, splendid as the food and music is, the real luxury of the walk is in the interactions. Life feels larger on the streets of the South Bronx. There are always people gathered on someone’s steps, and I can always find welcoming faces ready to talk and laugh and argue with me about my understanding of the neighborhood or my inexplicable belief that anything below sixty degrees Fahrenheit counts as cold or the ways New York City has changed over the past decade or half century.

This verve and neighborliness was everywhere I went in the South Bronx, no matter the circumstances. Most remarkable, to me, was Hunts Point, one of the South Bronx’s and New York City’s poorest neighborhoods—so much so it’s often cited as the Upper East Side’s economic polar opposite. In all the figures that economists quote to show standards of living and quality of life—median household income, percentage of population below the poverty line, life expectancy, educational-attainment levels—Hunts Point, a neighborhood of poor and working-class people, lies near the bottom when compared with other US neighborhoods in dire conditions. When I walk around Hunts Point’s industrial environment, with many of its residential houses four sighs away from collapsing, I’m struck by the nakedness, the vulnerability of the surroundings. Open spaces, with few trees to shade me, leave me exposed to the unrelenting tag team of the sun and heat-radiating asphalt. Recent development and revitalization efforts notwithstanding, the neighborhood has the aura of abandonment, particularly at night, where a motley gang of strip clubs, auto body shops, and prisons suggests backs turned.

Few, if any, people walk around the neighborhood just for walking’s sake. With the high crime and severe poverty, it’s a place that people who have no business there try to leave. Not that wayfarers are made unwelcome. Slow down a bit on its streets and you’ll run into friendly small talk and laughter that rebuke the glum backdrop. (It wasn’t all “happy town,” though: People also spoke as if their lives were like one of the short, shabby dead ends I sometimes encountered amid the neighborhood’s industrial landscape, and the very poor weren’t always in the mood for neighborliness). One night, not long after midnight, my ready-to-hoof-anywhere pal, Suketu, drove me along with two of his friends to the Hunts Point Food Distribution Center, popularly called the Hunts Point Cooperative Market. (Most New Yorkers who do know of it know it as where Manhattan’s beloved Fulton Fish Market was relocated to join markets that deal with fruit and vegetables and meat and poultry.) We hopped from market to market, talking with some of the thousands of mainly male workers employed by the various food wholesalers, distributors, and processors that are part of this fork-shaped collection of frigid warehouses and loading bays alongside the Bronx River.

Until shortly before sunrise, we learned more than we would ever need to know about the food coming from all over the world to this node before dispersing all over again. In the brightly lit produce market, we walked down corridors one-third of a mile in length, past a field of colors—lettuce, peaches, strawberries, sweet onions, tomatoes, scallions, lemons, corn, potatoes, peppers, and many more than we could take in. We kept craning our necks to sniff, four bumblebees hovering around berries and bananas and plums and other sweet-smelling fruit. The employees, for the most part, seemed puzzled that four grown adults were walking around at 2:00 a.m. for fun. We moved on to the meat market, where, in warehouse-sized refrigerators (or, so I considered the cold-to-the-bone spaces in which my teeth were chattering), there was meat and poultry, enough to make a vegetarian queasy for months. Men ought to cry their way through the entire workday in these subzero temperatures, but this was where the party was. The four of us learned about butchering, distribution, union issues at the market, the red-light district nearby, and other things that I missed because my breaking point is cold temperatures. The fish market was a stinky pleasure, its odor made bearable because of the laughter that suffused the atmosphere. I suppose if you are going to work with guts and funk, you had better have a sense of humor. And smiling faces, Duchenne smiles, were in abundance wherever we migrated.

As far as I could tell, apart from the four of us, the only people around were those who had business there. We were like four kids let into a playground alone after closing hours, roaming at random and clowning around with the workers—in one instance, taking a photo with a knife in mock plunge to one of our throats—and learning a bit from them about the neighborhood right outside the guard-protected gates of the markets. There was joy, but there was mainly bustling, since the work done there results in billions of dollars in receipts.

After five hours or so of moving among the different markets, the sky took on a hue that announced morning was on its way. We decided it was time to go, but we were with Suketu, so that meant that it was not a simple departure for home. Another adventure was to be found. Nocturnal being that I am, I was ready for whatever enjoyment he had ahead. But when we jumped in his car, I felt dislocated. The comfort of the car felt stifling, like a cocoon of glass and steel, and the artificiality of my movement—machinery taking me to my adventure, rather than my own two feet following my senses—dampened my zeal. I wasn’t being a sourpuss—near impossible around Suketu, with his radiating charm and humor—but I recognized the previous five hours of walking had only prepared me for more walking. In a car, I was too preoccupied with the landscape of my imagination, rather than attentive to the one before me. The music and movement of the car too easily displaced the movement and music of the streets I’d become used to. I felt I had at once lost and gained too much control; you ought to know where you’re going when you’re driving, and a surprise is the last thing you want. I wanted to be the “[a]foot and light-hearted” walker that Whitman praised. To “take to the open road, healthy, free, the world before me, the long brown path before me leading wherever I choose.” I wanted to be on foot. I wanted to meet other people on foot.

When we left the artery that was Hunts Point Market, the eerie silence outside felt condemning. The ailing conditions glared. No one was on the street. Prostitutes, who used to dot the neighborhood’s corners and sidewalks, had retreated inside due to the convenience of doing business online. (So we were told by some of the men we spoke to earlier—apparently reliable sources based on their remarks about after-work recreations.) We drove around a bit, past sidewalks now bare, where in the day I had numerous delightful conversations, raising my voice above the sound of loud freight trucks expelling foul exhaust. Hunts Point at night might as well be another neighborhood, I thought; I hadn’t recognized until then how much its residents imbued it with color.

On the way back home, Suketu drove through the Upper East Side, past glittery boutiques and sexy bistros, enticing department stores and showy high-rise apartment buildings. At that moment, I recognized that, for me, there wasn’t much difference between cutting through the neighborhood on foot and in a car. There was, of course. But leaving from Hunts Point, where time in a car away from residents removes so much of the neighborhood’s pleasure, and arriving in the Upper East Side around fifteen minutes later, only to recognize that I felt at arm’s length from a lot of its residents even when I walked through, reminded me that inequality also deprives the very wealthy. In ensconcing themselves in their circles, the very wealthy had cut themselves off from a range of perspectives and temperaments and stories—stories that are a central part of their city’s vibrancy and appeal. In Hunts Point, I witnessed deprivation due to an absence of resources; in the Upper East Side, I witnessed deprivation of a different, but related sort: the absence of enriching interactions.

I became an obsessive walker as a matter of necessity. Too poor to take taxis when I was growing up in Jamaica, and living in a neighborhood where taxis (and, alas, friends) refused to go at night, I learned to walk wherever and whenever to get home. This meant walking through some very dangerous parts of Jamaica. Observation was more about survival—Will he rob me? Will he stab me? Will they shoot me?—rather than about exploration: What will she tell me about this city? What will I learn about my country? Myself? Eventually, by the time I was able to afford cabs, it had become natural for me to venture all over the island, because some frequencies I could only hear while on foot. My interactions with others would enlarge and fortify my identity. And there was something exhilarating about participating in the oldest of rituals: human dealings through the sharing of stories.

One pleasurable afternoon when spring was showing off and pulling everyone out of their homes, only to smirk “Gotcha!” and hit them with a heavy downpour, I took an acquaintance, Genevieve, to the South Bronx. She’d asked to explore it with me but I thought that the wet outdoors would make our walk a letdown. We walked around, wandering down streets that looked interesting because of the architecture, or, more commonly, because of liveliness on their corners and sidewalks. We stopped to talk to a young man laying mulch on his front-yard garden. “Yeah, it comes in all colors these days. I like the look of the red,” he obliged, as I cut into his gardening time. He was focused on packing fertilizer around the roots of flowers that had just begun to bloom, and nightfall wasn’t far away; he had the urgency of a man trying to beat the clock, either to race the coming of dusk, or to be on his way out to enjoy the night. Nonetheless, he leaned back, arms akimbo, and spoke with us about gardening.

I asked directions of a woman on the sidewalk waiting for friends: “Uh-huh, take that street to go to the park. You’ll see the playgrounds on the way.” And so it went—moment after moment of stopping people to ask for directions (even when we knew where we were going; I discovered some time ago that New Yorkers are all too ready to play compass and map to those who ask, and a question for a location could become a conversation about the neighborhood). The dampness seemed to have had no effect on the neighborhood’s exuberance. People were playing music and enjoying it with friends on their porches. Pick-up basketball games were all around. And just about everyone we passed exchanged a pleasant smile or greeting. Even when we cut into their gardening time.

After a few hours of wandering, we went to a Nigerian eatery named Patina African Restaurant, a homey spot made more so by the conviviality of the staff and fellow diners. We began talking with a waitress who said she was from Sierra Leone, and whose name, Ayomie, which means “joy,” could not have been more befitting. She was busy befriending us while juggling a bunch of responsibilities, and helped Genevieve with her decision-making: “Your first time here? Okay, I’ll give you a sample of everything so you can decide what you want.” When she found out that my travel companion’s name was Genevieve, she yelped excitedly and it seemed her only job after that was to inform all the women hard at work in the back cooking, cleaning, and organizing that “Her name’s Genevieve.” People came out and looked at Genevieve and smiled and asked if she knew. Well, now she did. It turned out that Genevieve is the name of a beloved Nigerian singer and actress, and I might as well have been sitting across from her, for there was such palpable excitement about the one I knew that I was sure I’d brought a celebrity to eat with me. A week or so later, Genevieve told me that she was speaking with someone from Africa and mentioned her name as “Genevieve, like the singer,” and that simple acknowledgment led to a more amusing and pleasing exchange.

The stories people tell each other and the stories they allow themselves to encounter are part of what gives New York City its energy. And the stories I heard ignited my imagination and reshaped my ideas about the city. One afternoon during my physical therapy session, I had one such chat with a patient who was part of the neighborhood’s elite. She was a college professor—of English literature, if my memory hasn’t deceived me—in her seventies, not much more than five feet tall, and overflowing with warmth and élan – more cute-aunt than authoritative dispenser of knowledge. Her friendliness, conveyed with a mellifluous voice, made me stop my rehabilitation exercises and listen away. She spoke about the world with unbridled enthusiasm and genuine wonder, and her drive to explore it made me want to cut her off and rush in search of her adventures. But what stayed with me weren’t the wonderful stories.

I’ve unfortunately forgotten them all, inspiring as they were—but, rather, it was her ability to give one a greater sense of possibility. I often wish I could take this woman on my walks. A greater sense of wonder, a greater sense of the multifariousness of the world, a greater sense of possibility: These gifts she bestowed, and these were what I most wanted to dispense when I crossed the divide to where people too often were in desperate need of these traits along with resources.

Serendipity reveals a world of people holding views and undergoing experiences unlike ours. But serendipity also exposes our commonalities, showing how much our joys and frustrations and anxieties are similar: We all want happy marriages and healthy children and kind in-laws; we all want what we think is best for our children; and we all feel helpless and crumble in the face of mortality. Inequality manifests itself both as the inequality of resources and, looking in the other direction, the inequality of interaction. But, really, everyone is diminished by the absence of interaction, the lack of shared experience. The very wealthy and very poor—inequality makes equals of them all.

“Due North” is excerpted from Tales of Two Cities: The Best and Worst of Times in Today’s New York, edited by John Freeman, and will be published by OR Books, in association with Housing Works, on October 23, 2014.

Ruddy Roye is a Brooklyn-based documentary photographer specializing in editorial portraits and photojournalism.