Those Glorious Fan Magazines

The following post by Anne Helen Petersen is part of our online companion to our Winter 2013 issue on Classic Hollywood. Click here for an overview of the issue.

———

We know what Hollywood publicity looks like today: proliferating gossip blog posts, paparazzi shots on TMZ, carefully cultivated Tumblrs featuring “candid” photos taken by the celebrity’s full-time leisure photographer. Contemporary publicity is at once carefully orchestrated and wholly unpredictable, with only the most conscientious of celebrities capable of completely controlling the narrative of what their images “mean.” Jay-Z and Beyoncé are particularly good at it; the Kardashians oscillate between masterful control and laughable attempts to shift and shape public perception. Even the most mindful stars, with the most skilled publicists, struggle to control the story, in part because there are just too many voices, often woefully discordant, trying to tell it.

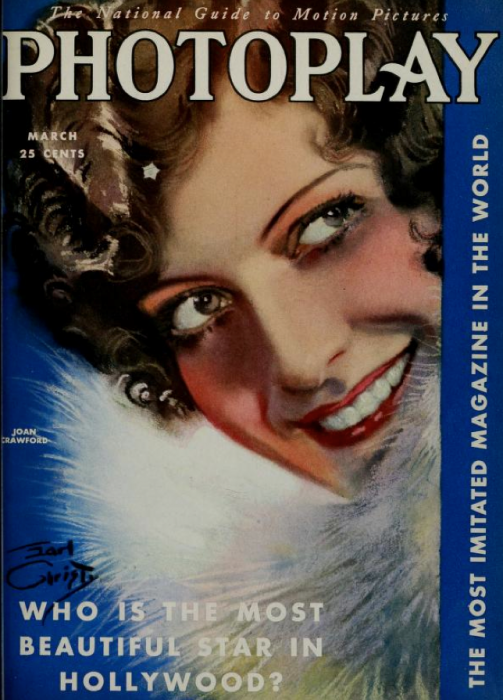

But back in the halcyon days of classic Hollywood, the fan magazines had a monopoly on star publicity—and the rhetorical maneuvering, the delicate yet forceful construction of hundreds of star images, are a marvel to behold. Between 1910 and 1970, there were dozens of fan magazines, each with various periods of longevity, focus, and targeted demographics. The more full-color portraits, the less pulpy the paper, the more obvious cooperation on the part of the star, the higher the target demo. And the queen of the magazines, the People meets Vanity Fair, the veritable doyenne of Hollywood publicity, was Photoplay. Others were important—Modern Screen and Motion Picture deserve mentions—and the gossip mavens (Louella Parsons, Hedda Hopper, Walter Winchell) all had larger daily audiences. But no magazine did publicity quite as smoothly, and with as much aplomb, as Photoplay.

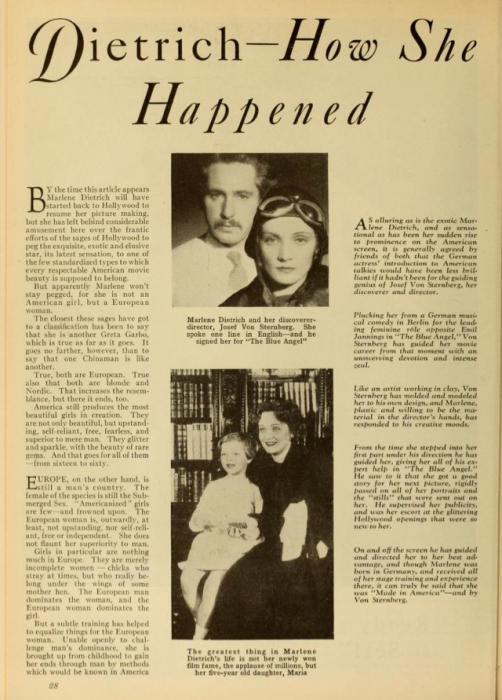

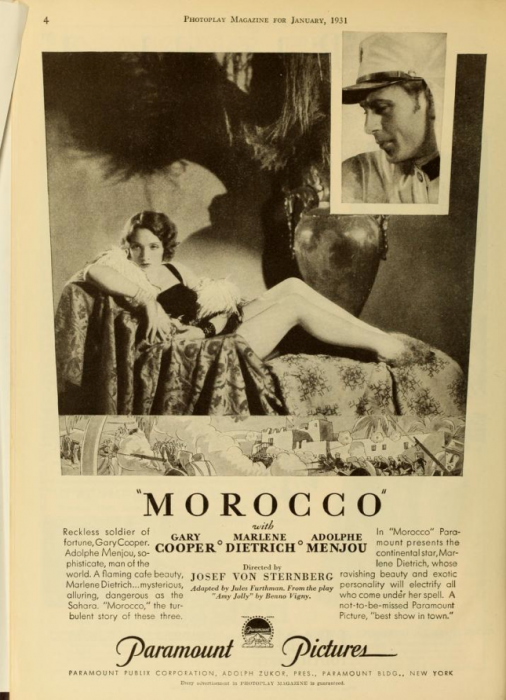

Photoplay was only able to play this role with the complete cooperation of the studios. In exchange for publicizing their stars—and publicizing them in a very precise way, almost wholly dictated by the studio’s publicity department—the studios agreed to massive ad buys. On one page, an advertisement for Marlene Dietrich’s new picture; on the next, a profile of “How She Happened.”

It’s not an unfamiliar tactic—today, we just call it synergy—but the difference was that Photoplay, unlike People, was not owned by a media conglomerate. Rather, it simply committed to a form of market symbiosis that sustained the classic age for several decades, slowly disintegrating alongside the studio system itself in the 1950s.

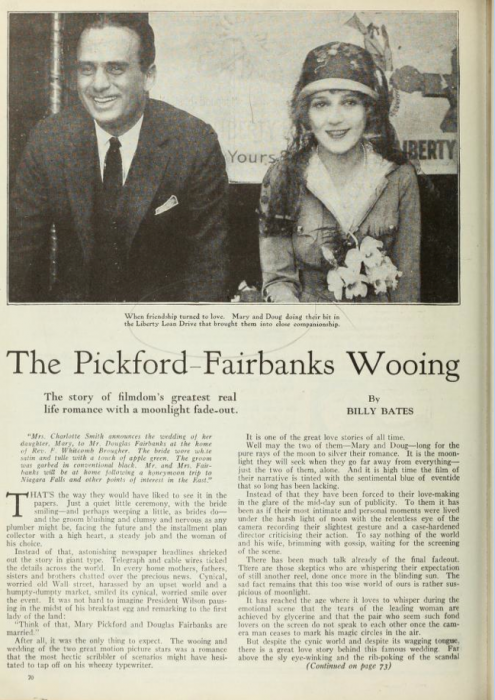

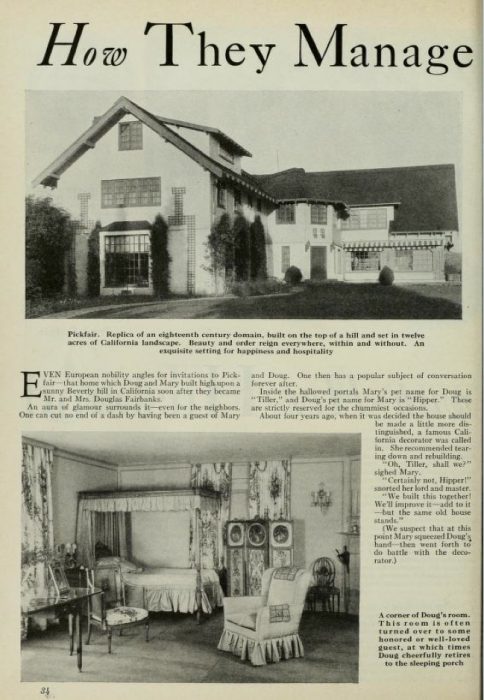

But from the late 1910s through the 1940s, Photoplay ruled supreme. In the beginning, its tone was inflected with that of its editor, James Quirk, a champion of early Hollywood and close collaborator with various industry powers-that-be, including Will Hays, head of the censorship board. In the early 1920s, when a cluster of potential scandals threatened to taint the reputation of the so-called “movie colony,” Quirk understood the power of his publication to help ease anxiety. Photoplay spreads helped to turn the divorces of Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks—and their subsequent marriage to one another—into a narrative of “true romance.”

Photoplay performed the same function as a (successful) interview with Oprah, as a much-lauded appearance on a late-night show, as a beautiful Oscar dress or a paparazzi-documented perfect date to the Central Park Zoo—and it did it for audiences of millions, women and men of all ages.

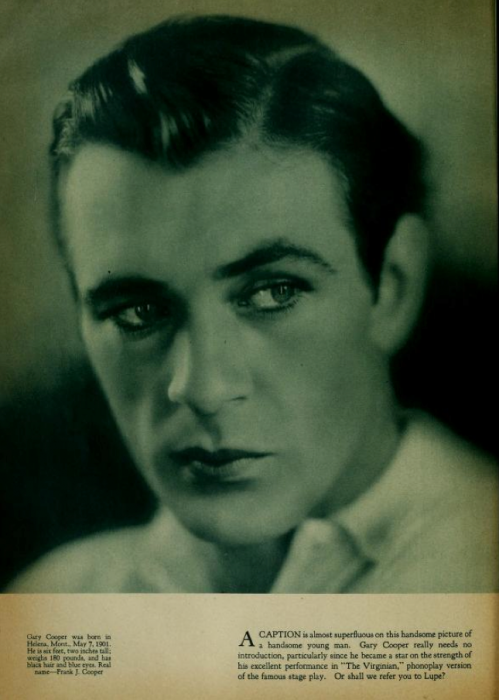

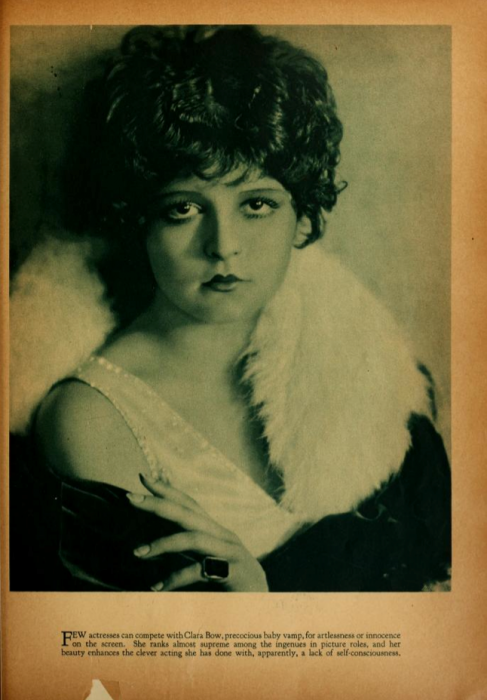

There were “rotogravures,” the 1920s version of the Teen Bop poster you’d pull out and tack above your bed:

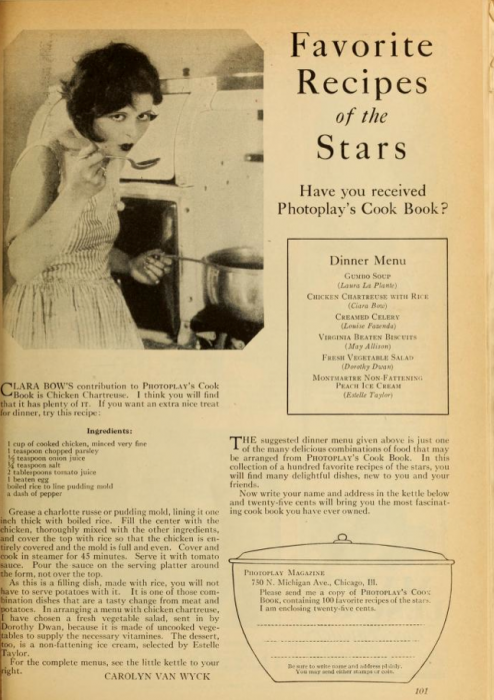

There were glorious spreads that attempted to align the stars with consumption—and, thus, Americanism, effectively establishing “buying things” as their primary Hollywood activity, rather than the much more lurid “drinking a lot and having extra-marital sex.”

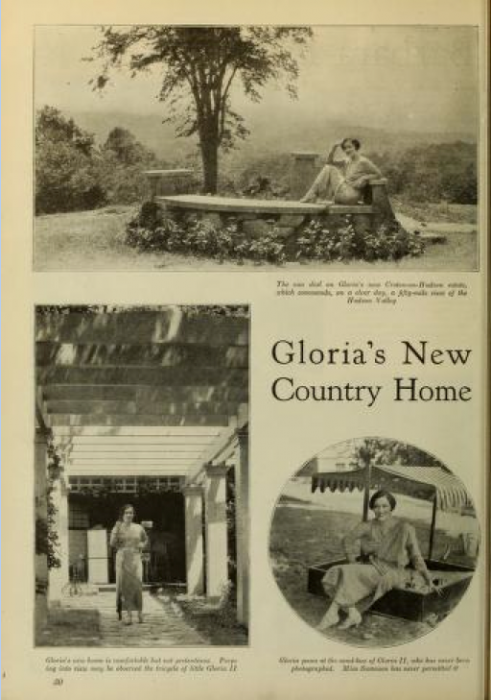

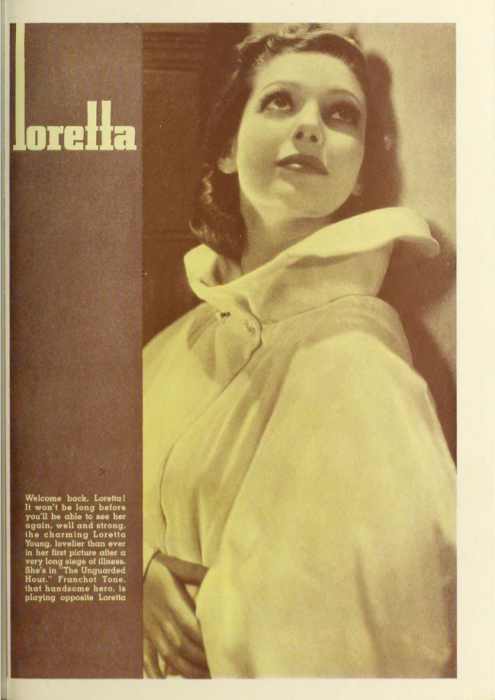

There were images that aligned female stars with domesticity, just in case you were worried that they were actually forsaking traditional gender roles while making hundreds of thousands of dollars.

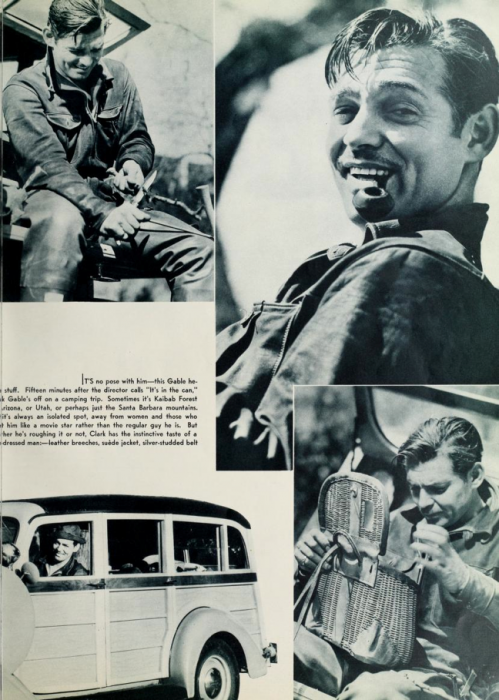

And most importantly, there were long-form narratives that set up a star as a particularly American product: no matter how “exotic” the background (Pola Negri was from Poland; Gloria Swanson grew up in Puerto Rico), the studio press agents and Photoplay writers helped craft a star image that was white, Christian, heterosexual, and overarchingly American. Even the most wild of “Pre-Code” women became demure and fawning, while male stars funneled their energy into fishing and hunting trips.

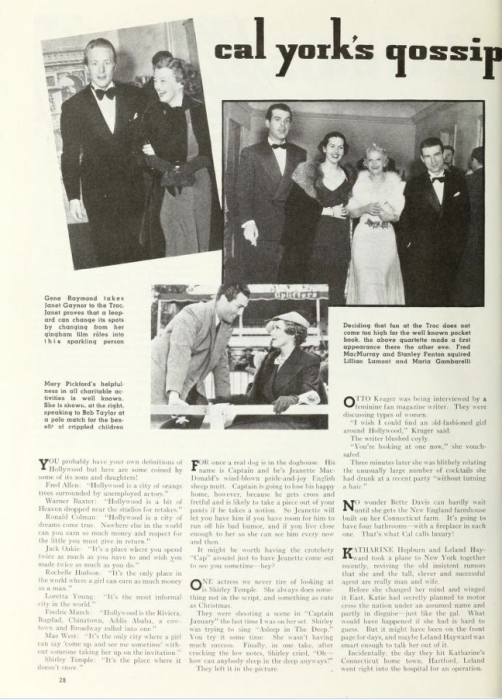

Romance was celebrated; divorce explained and excused. Real gossip was available for those who could read between the lines on the eight-to-ten-page “gossip” sections—”Katharine Hepburn and Leland Heyward took a plane together to New York recently,” York wrote, “reviving the old insistent rumors that she and the tall, clever and succesful agent are really man and wife.”

But when real scandal did go down, Photoplay avoided it: print no evil, see no evil. Indeed, the fan magazines in general were complicit in the studio-headed cover up of all untoward behavior on the part of the stars—if a star serially cheats on his second wife and impregnates his co-star, who then gives birth to a child, gives it up for adoption, then “adopts” an orphan with ears that match those of that star’s former co-star, but no one says a word, did it actually happen?

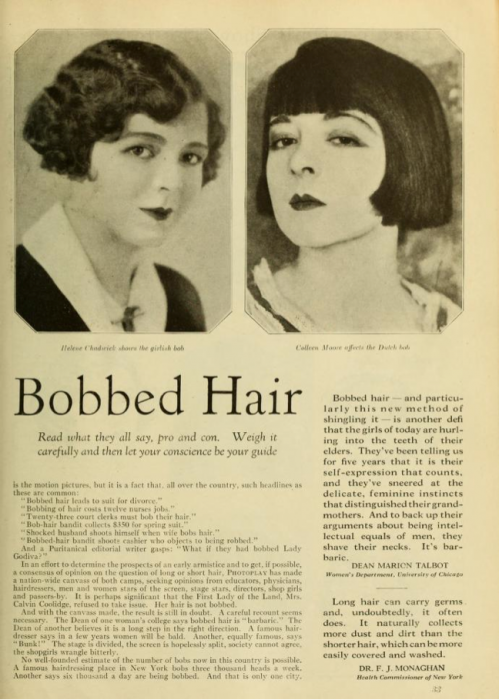

The magazine also offered fashion tips, effectively setting up stars as models whose style and look the reader should emulate—especially through purchase of products, including hair dye and fashion lines, conveniently advertised in the magazine’s pages.

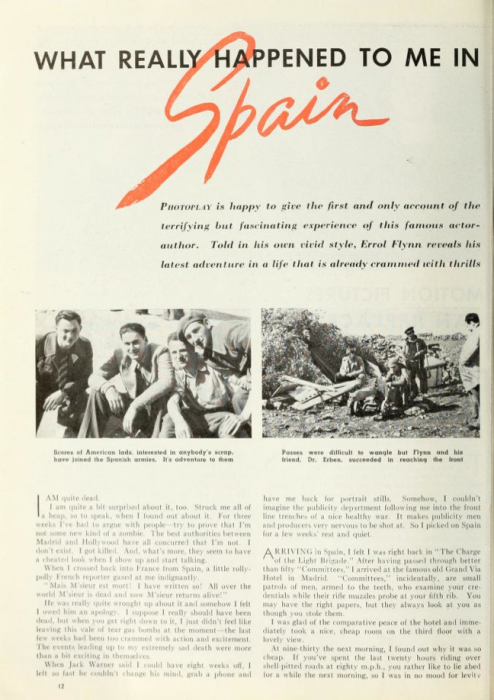

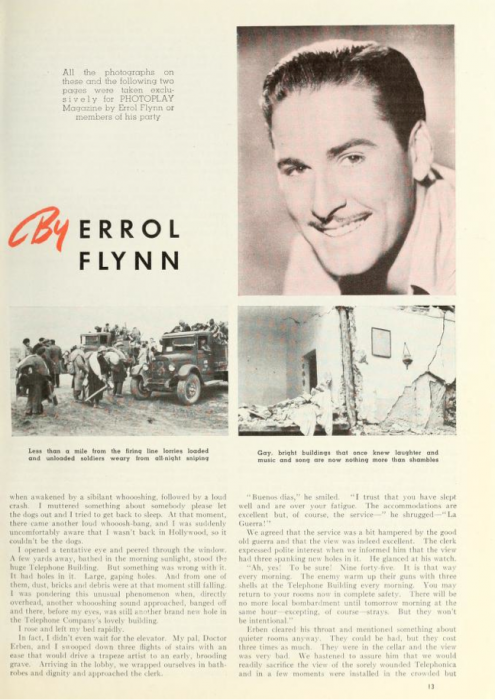

Sometimes, stars themselves would pen articles—again, these were almost certainly written by press agents—defending themselves, “setting the record straight,” or otherwise manufacturing a cloud of authenticity around the formation of their star image. My personal favorites come from Errol Flynn, who authored a series of “Man About Hollywood” columns in the late 1930s:

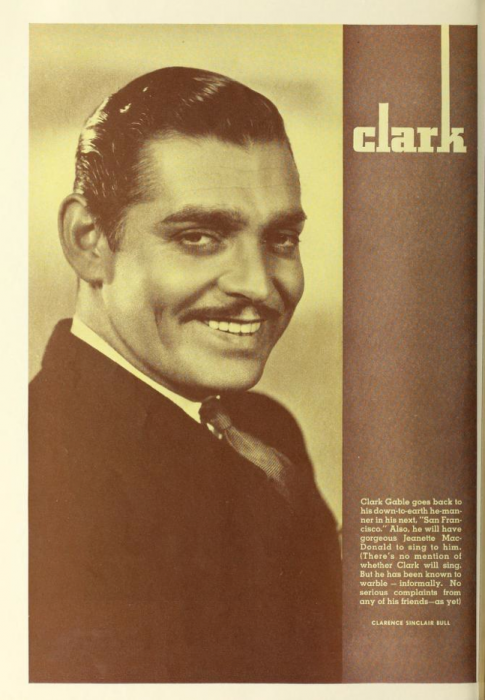

These articles not only set up a particularly dashing and debonair inflection to the swashbuckling masculinity he had established onscreen in Captain Blood and The Adventures of Robin Hood, but framed him as a curious, creative writer. He wasn’t just Warners’ answer to Clark Gable: He could write. And whether or not he actually did author these articles matters little, lest you’re the type who’s deeply invested in Flynn—what matters is that he was overwhelmingly signified in this way.

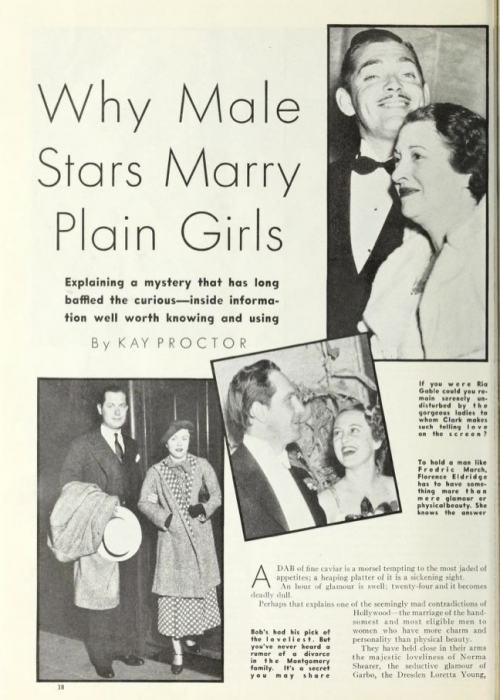

As much as I love the star-authored articles, they have nothing on the fan-magazine editorial. The editors of these magazines took themselves, and their place and power in Hollywood, very seriously. Sometimes they used their podium for good—defending Clara Bow, for example, from the attacks levied on her by nefarious, nasty tabloiders in the early 1930s. But most often, they used it for bizarre ideological purposes. They reified the gender roles in the home, problematized fashion trends that threatened the status quo, and explained why Hollywood stars marry plain girls.

When I say “bizarre” I don’t mean to suggest that they were perceived as odd or absurd at the time. The editorials, just like the star images themselves, communicated volumes concerning what values mattered to the majority of Americans at the time: what cultural edifices needed support, and if compromised, required meticulous rhetorical masonry to repair.

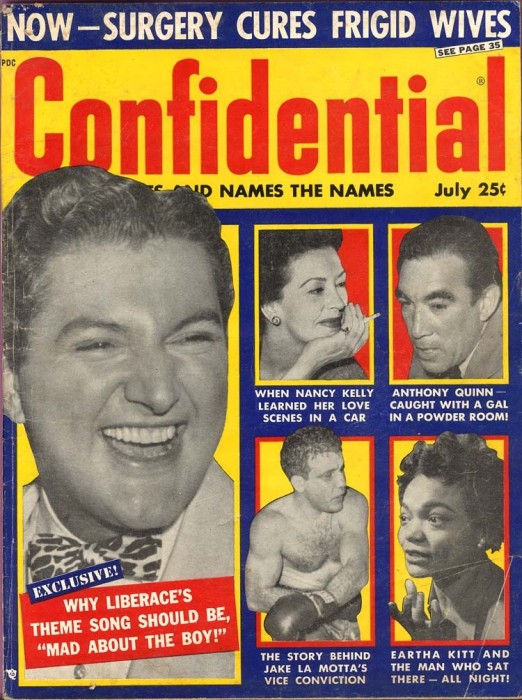

The gossip industry is rarely progressive. Indeed, the vast majority of gossip is used as a club to beat those who don’t conform back into place. If anything, the scandal press—bombastic yellow journalism in the early part of the twentieth century, Confidential Magazine in the 1950s, the National Enquirer from the 1960s to the 1980s, and TMZ today—are the most progressive of their ilk, if for the simple reason that they make the unspeakable speakable, the invisible visible. They open up discourse and start conversations, even if their own discourse can, at times, slant homophobic, xenophobic, and racist.

But the traditional gossip press, the Photoplays and Entertainment Tonights, the People Magazines and Just Jareds, has always had a very clear purpose: toe the publicity line. Shore up the status quo. Reassure audiences in what they want to believe. The stars are who we think they are, they represent what we want them to.

As long as we have stars and celebrities, we’ll have a press that upholds what they want to mean and a press that undercuts that belief. During classic Hollywood, the studios succeeded in nearly silencing all publications—all “voices”—that spoke contrary to what they wanted the public to believe. It was, as they say, the golden age. Stars were more beautiful, the movies in which they appeared, and what they seemed to represent, all the more shiny. But beneath that shiny exterior, like the plot of classic film noir, lay all matter of deceit, infidelity, debauchery, and drunkenness.

Today, we like to believe that the proliferation of gossip sites, the skill of the paparazzi, and the general clumsiness of celebrities when it comes to social media renders all things known—all the secrets have been told. But the more you learn about the way that People works within Time Warner, the more you understand about how TMZ is owned by the same conglomerate, the more you listen to the avid attestations from both that they remain free of conglomerate oversight, the more you realize that the publicity game only seems to have changed.

We don’t have Photoplays anymore. But we do have all matter of publicity outlets, functioning within the greater celebrity industrial complex, that buttress various ideologies, some more insidious and destructive than others. I love reading old Photoplays because the manipulation is so obvious, even ham handed, even as it attempts to elide its own existence. I’m sure some readers looked at Photoplay in 1928 and threw it down with disgust. But for most, the ideological maneuverings were invisible, if only because these readers were, in Louis Althusser’s phrasing, interpellated by them—these stories spoke to readers, and those readers answered by reading, believing, consuming.

I’m left to wonder: how does People speak to me today? There’s much that I, as a scholar of film history, can readily see, but what remains invisible? And what will the scholars of the future tell us of our particular publicity moment—and our society’s eagerness to believe ourselves immune?

———

Also: Read Anne Helen Petersen’s “The Rules of the Game: A Century of Hollywood Publicity” (VQR, Winter 2013)

About the author: Anne Helen Petersen received her Ph.D. from the University of Texas at Austin, where she wrote her dissertation on the industrial history of celebrity gossip. She is a member of the media studies faculty at Whitman College in Walla Walla, Washington. She writes the “Scandals of Classic Hollywood” column for The Hairpin and blogs semi-regularly at Celebrity Gossip, Academic Style.