Reading the Pictures: Graphic Novels

For my generation, comic books received a bad rap. Parents were convinced comics were a contributing factor to a great epidemic of juvenile delinquency and a concomitant claim that the readers of comics were, by definition, stupid. It was not until the publication of Art Speigelman’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Maus: A Survivor’s Tale (Pantheon, 1986) that the cultural stature of comics, now called “graphic novels,” underwent revision. Though there was some of the usual grousing by interested parties about what defined the “new genre,” my sense of the distinction between the old-style superhero comics and their more recent cousins is something approximating the difference between cartoons featuring Mickey Mouse or Tom & Jerry and recent films like Toy Story and Shrek.

Of course, some shrewd publisher had already anticipated the pedagogical utility of picture stories (as Ben Katchor calls them) by creating fully illustrated versions of great literary classics, originally known as Classic Comics, then Classics Illustrated: A Cultural History, With Illustrations (McFarland & Co., 2001).

These pulp fictions have been superseded by a thriving “A Such and Such for Dummies” industry. And not to be outdone by publishing hucksters, the US government found it useful to employ comics in various propaganda initiatives; histories include Comic Books and the Cold War, 1946-1962: Essays on Graphic Treatment of Communism, the Code and Social Concerns, Chris York and Rafiel York, eds. (McFarland & Co., 2012) and Government Issue: Comics for the People, 1940s-2000s by Richard Graham (Abrams ComicArts, 2011).

The late 1960s comics took on a kind of bent humor, with such masters as Robert Crumb, Gahan Wilson, B. Kliban, and Glen Baxter. Until recently, the definitive book on the genre was still Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art (William Morrow, 1993).

Now comes three volumes of Russ Kick’s The Graphic Canon,of which the third volume, “From Heart of Darkness to Hemingway to Infinite Jest” (Seven Stories Press, 2013), offers an amazing (and I mean amazing) anthology of more than seventy graphic adaptations of world literature and acts as a kind of survey of visual narratives and a useful retrospective on comics qua comics.

Some people enjoy submerging themselves in the massive biographies that detail all manner of minutiae (which no doubt reveal how the child became the man or woman). For you, there is James Gleick’s Genius: The Life and Science of Richard Feynman (Vintage, 1993). The rest of us might do better with Feynmanby Jim Ottaviani and Leland Myrick (First Second, 2011).

And while there is great value in Jon Lee Anderson’s Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life (Grove Press, 1997), less dedicated readers will find Spain Rodriguez’s Che: A Graphic Biography(Verso, 2008) useful.

The Autobiography of Malcolm X (Ballantine Books, 1965) is anurtext in black American history, but a useful adjunct is Malcolm X: A Graphic Biography by Andrew Helfer and Randy DuBurke (Hill and Wang, 2006).

If you are aware of Leon Trotsky, beyond his name being taken as an insult within progressive political circles, good for you. Otherwise Tariq Ali’s (with Phil Evans) Leon Trotsky: An Illustrated Introduction (Haymarket Books, 2013) is a useful primer on the great Bolshevik theoretician.

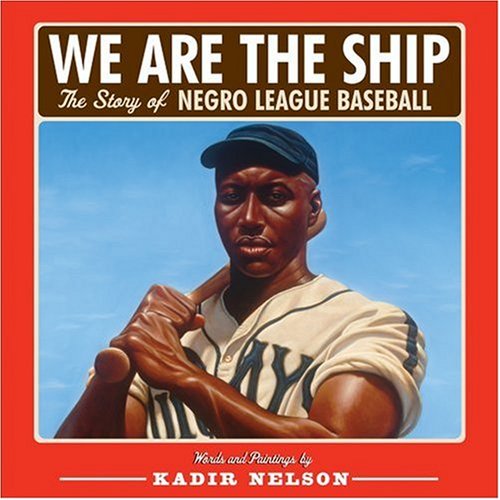

Baseball is rich with great and colorful personalities, and 21: The Story of Roberto Clemente by Wilfred Santiago (Fantagraphics Books, 2011) and Satchel Paige: Striking Out Jim Crow by James Sturm and Rich Tommaso (Hyperion Books, 2007) are outstanding exemplars of graphic storytelling. Also, Major League Baseball has done some work establishing the importance of the Negro Baseball Leagues. (Think of 42,the bio pic of Jackie Robinson). One of the best books I have seen on this subject is by artist Kadir Nelson, We Are the Ship: The Story of Negro League Baseball(Hyperion Books, 2008), which is richly illustrated by full-color, full-page paintings, touching on the main points of black baseball lore and its legends.

If the books already listed aren’t sufficient to support the seriousness of intent and purpose of graphic-book authors, one need look no further thanA People’s History of American Empireby Howard Zinn, Mike Konopacki, and Paul Buhle (Metropolitan Books, 2008). While no substitute for Zinn’s magnum opus, A People’s History, this tome does make that 800-page book more accessible.

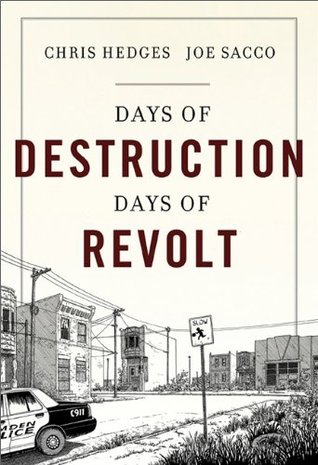

American underground comic-book writer Harvey Pekar takes on the quagmire of Israel’s existence with Not the Israel My Parents Promised Me (Hill and Wang, 2012). And Joe Sacco’s recent collaboration with Chris Hedges, Days of Destruction, Days of Revolt(Nation Books, 2012), is a stirring, heartfelt look at and critique of “the sacrifice zones, those areas in America that have been offered up for exploitation in the name of profit, progress, and technological advancement.”

Sacco’s forthcoming The Great War: July 1, 1916: The First Day of the Battle of the Somme(with Adam Hochschild; W. W. Norton & Co., 2013) looks to become a classic of the genre, as was Art Spiegelman’s Maus.

Still more volumes to consider:

• There is no shortage of advocacy in graphic narratives—none more dramatic than animal-rights activist Sue Coe’s oeuvre, led by her opus,Cruel: Bearing Witness to Animal Exploitation (OR Books, 2007).

• At least for writers, The Elements of Styleby William Strunk, Jr. and E.B. White (Harcourt Brace, 1919) qualifies as a classic, and the inimitable Maira Kalman transforms it in The Elements of Style Illustrated(Penguin Books, 2005).

• MacArthur Fellow Ben Katchor’s body of work is a study in originality, and his latest book, Hand-Drying in America: And Other Stories(Pantheon, 2013), carries on his amusing take on the quotidian. Curious minds will want to delve into the workings of “The Brotherhood of Immaculate Consumption” and other bizarre imaginings of Katchor.

• And speaking of offbeat originals, Red Handed: The Fine Art of Strange Crimes by Matt Kindt (First Second, 2013) is an amusing takeoff of hard-boiled noir, set in the city of Red Wheelbarrow and driven by the genius of master detective Gould.

———

About the author: Robert Birnbaum’s Social Security number ends in 2247. He lives in zip code 02465 and area code 617. He was born in the 2nd month of a year in the 20th century. He doesn’t social network (used as a verb) except through his Cuban retriever Beny (named after Beny More, the Frank Sinatra of Cuba). Izzy Birnbaum also has cloud storage and uses electronic mail. He hopes his son Cuba is the second coming of Pudge Rodriguez. He mutters to himself at Our Man In Boston.