Like a Novel

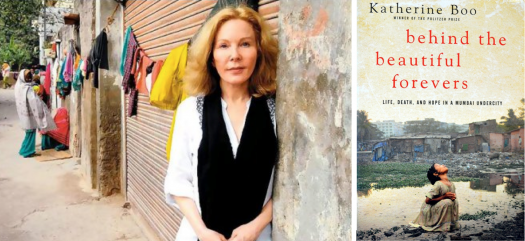

I recently read KatherineBoo’s 2012 National Book Award–winning portrait of a Mumbai slum, Behind the Beautiful Forevers, with my students in a creative nonfiction class at Dartmouth College. Boo spent a little more than three years in the slum, Annawadi, practicing what’s sometimes known as immersion journalism. It’s a term she may have taken too literally: “To Annawadians,” she writes in an author’s note, “I was a reliably ridiculous spectacle, given to toppling into the sewage lake while videotaping.” That’s close to all we know of her adventures, though, because Behind the Beautiful Forevers is written in a voice that might be called “strictly third person.” Besides that note, there’s no hint of Boo’s presence in the lives of the slum dwellers.

“Dickens,” observed one of my students—as in Charles, as in fiction. The word “paternalism” arose, though more as a question than a charge: Did Boo, in assuming the role of an omniscient narrator, inadvertently set herself up to look down on Mumbai from on high? Another student wondered why one of the blurbs on the back was from David Sedaris. “Isn’t he, like, funny?” Behind the Beautiful Forevers is not a funny book, but it wasn’t the blurb-presence of a humorist that caught my student’s eye. It was what Sedaris wrote: “It might surprise you how completely enjoyable this book is, as rich and beautifully written as a novel.”

Emphasis mine, cliché Sedaris’s. Should we blame him? He liked the book. He wanted people to read it. And Sedaris is nothing if not a savvy salesman. He must’ve understood that the promise of “enjoyment,” married to all that is implied by a novel—characters, plot, resolution, a seamless world—would give Behind the Beautiful Forevers a readership far beyond the market share for true tales of relentless filth and poverty. Especially if the promise is made by a bestseller such as himself. “Reads like a novel”—that’s the elevator pitch. That’s how you sell suffering for $27.

Tom Wolfe made the phrase like a novel his own in the introduction to his influential 1973 anthology, The New Journalism. “Like a novel, if you get the picture,” he wrote; emphasis his. Wolfe really did have Dickens in mind, nineteenth-century fiction that derived its “unique power” from its “immediacy.” But immediacy is an illusion, the disguise of the mediation that is the author standing between you and the reality depicted by the story. Immediacy is fiction. It’s what screenwriter Ed Burns, in an episode of The Wire about falsified you-are-there newspaper stories, derides as “the Dickensian aspect.” Offered up by blurbers with the best of intentions, the immediacy implicit in like a novel suggests that the book on hand can be engaged with as art rather than as fact, so realist it’s not real; a story rather than the state of things, a condition in which we might be complicit. The blurber may be speaking of craft—the use of scene, dialogue, character—but publishers traffic in genre, the overstated distinction between art and fact that makes one book “current events” and another “a timeless story”—that is, a book with a shelf life.

Adrian Nicole LeBlanc’s Random Family: Love, Drugs, Trouble, and Coming of Age in the Bronx? “Like a novel.”

Michael Lewis’s The Big Short, a hair-pulling anxiety disorder of a book about financial ruin? “Like a novel.”

Sonia Faleiro “brings a novelist’s eye” to another account of degradation in Mumbai, Beautiful Thing; Aman Sethi, author of A Free Man: A True Story of Life and Death in Delhi, “possesses a novelist’s ear.” I’ve never heard the nose of a literary journalist compared to that of a novelist, but there’s no shortage of praise within the genre for “pungent details,” the kind novelists are thought to be especially good at producing.

To be “like a novel” seems in many other renderings to be a sort of spiritual condition. In The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down, a winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award, Anne Fadiman explores a tragic culture clash between Western medicine and a Hmong immigrant family with what Richard Bernstein in the New York Times describes as “a novelist’s grace”; William T. Vollmann rambles through the history and statistics of poverty in his nonfiction Poor People with “a novelist’s grace,” according to Esquire. Powell’s markets Blood Done Sign My Name, Timothy B. Tyson’s astonishing hybrid of history, memoir, and reportage, as written with the “eloquent grace of a novelist.” Grace is a gift, of course, and in this sense it functions as a modern metaphor for the muse, and a romantic conception of writing at odds with reporting.

It’s not just literary journalism. Historian Kevin Boyle’s erudite account of Jazz Age race relations and murder, Arc of Justice—also a National Book Award winner—“holds the reader like a fast-paced detective novel,” according to the Washington Post. Greg Grandin’s Fordlandia, a National Book Award finalist, “illuminates the auto industry’s contemporary crisis [and] the problems of globalization,” warns the Los Angeles Times, but don’t be deterred—it’s “recounted with a novelist’s sense of pace.” (Presumably not Proust’s.) Worried that the brutal details of the eighteenth-century slave trade might be too pungent for an enjoyable read? Don’t fret—Bury the Chains, the National Book Award finalist by Adam Hochschild, possesses the “dramatic power of a great epic novel,” says the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

These are brilliant books, all, pulled from my own shelf. But I’d dread the novel that delved into the economics of the slave trade with as much cool detail as Bury the Chains; and much of the interest in Beautiful Thing lies in the ways Faleiro’s subject, a bar dancer named Leela, fails to resolve as a “character.” That’s because she isn’t a character, she’s a human being who has been partially documented by Faleiro. It’s no insult to Faleiro to note that her documentation is incomplete, that she can never know her subject as well as she knows the characters in the novels she writes. The best nonfiction recognizes the impossibility of perfect representation, the dream of the 1:1 ratio.

Sometimes that acknowledgment is explicit, as in James Agee’s lament in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men that he cannot offer, instead of words, a box full of “lumps of earth, records of speech, pieces of wood and iron, phials of odors, plates of food and excrement.” Sometimes it’s just a nod, albeit a crucial one, as in Boo’s description in her author’s note of her prolonged attempts to draw the unarticulated thoughts of some subjects to the surface, where they could be rendered in approximate English by Boo’s translators.

So why, my students wanted to know, would Boo want her masterpiece of reportage, its “pungent details” acquired only with great effort, to be described as “like a novel”? If she’d wanted to write a novel, why hadn’t she? If she hadn’t wanted to write a novel—if the actuality of Abdul the trash sorter and Sunil the scavenger mattered to her—why wouldn’t she bridle at the comparison?

I didn’t have a ready answer. My own work has on occasion been compared to a novel, and whenever it was, I was delighted. I knew that for a book to be “like a novel” meant that it was safe for mass consumption. I knew that to be “like a novel” meant sales, even though nonfiction outsells fiction. But facts like that are beside the point. For Sedaris to say that Behind the Beautiful Forevers is like a novel is to reassure the reader that the suffering documented on every page isn’t what matters. It’s the experience. The reader’s, that is. This book will make you feel close to that suffering, but not too close.

Boo’s reviews are almost uniformly positive, with only one really notable exception at the Times Literary Supplement. TLS assigned Behind the Beautiful Forevers to the legal philosopher Martha Nussbaum, who faults the book for failing to offer a reform agenda in response to the poverty it depicts. Nussbaum seems wholly innocent of the tradition of literary journalism, of which muckraking is just one strand, but there’s a sense in which she’s taken the idea of “like a novel” seriously, and followed with a logical question: “What kind of novel?” Dickens, yes; and what does that tell us? “The English novel was a social protest movement from the start,” she argues, “and its aim (like that of many of its American descendants) was frequently to acquaint middle-class people with the reality of various social ills, in a way that would involve real vision and feeling.”

Along with Wolfe, it seems, Nussbaum feels that such novels possess “a unique power.” But where Wolfe seeks sensation, Nussbaum believes these realist novels should result in “constructive action.”

You may, like me, be wincing: The philosopher seems to have missed the point of fiction, a genre distinct from the petition and the manifesto. “If readers are to be steered in the direction of intelligent action aimed at change,” writes Nussbaum, “the narrative journalist needs to give them not just sympathetic characters, but also historical and economic analysis.”

The idea of Boo “steering” her readers to “intelligent action” smacks of a more troubling kind of marketing altogether, even if Nussbaum’s definition of such action is compatible with all the most high-minded ideals. But in a way, Nussbaum has stumbled backward into the problem with the notion of nonfiction being “like a novel.” In staking its limited representation of the world on a relationship to fact, every work of literary journalism asserts at least an implicit historical analysis, if not an economic one.

Nussbaum compares Behind the Beautiful Forevers to Rohinton Mistry’s novel A Fine Balance, also about an Indian slum. As fiction, Boo’s work couldn’t stand the comparison; as nonfiction, though, her book shines with what Agee called “the cruel radiance of what is.” It isn’t like a novel because it’s true. True not in the abstract sense, the sense in which novels may possess truth, but trued, like a wheel, aligned as closely as possible with arguable facts. That attempt—and its inevitable failure, too—matters more than “sympathetic characters.”

That attempt is one of the two essential facts of any work of documentary prose; the failure of the attempt is the other. We can true a wheel, but to some degree it will always wobble. We can research and fact-check and interrogate every assumption, every mark of punctuation, but the words are not the things they stand for, only coded approximations. That’s what literary journalism is: an approximation. It’s not like a novel, it’s like nonfiction, only it hasn’t quite gotten there. It’s still trying.

So, since like Sedaris I want you to read Behind the Beautiful Forevers even though it’s not “immediate,” even though it’s not illusion but rather documentation—to the best of Boo’s perception—of a reality all too common but perhaps startling to the average American middle-class book buyer, I’ll just say this: It may surprise you how enjoyable this book is, as rich and beautifully written as if everything in it were true.

That’s the ambition.

——

About the author: Jeff Sharlet, a contributing editor to VQR, teaches literary journalism at Dartmouth College. He is the author or editor of six books, including The Family, Sweet Heaven When I Die, and Radiant Truths, forthcoming in 2014.