A Detective for a Topsy-Turvy World

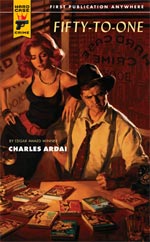

This month, New York magazine ran a short—and surprisingly flat—piece on Charles Ardai’s new pulp novel, Fifty-to-One. Discerning readers will recognize Ardai as the mastermind behind the Hard Case Crime imprint, which has in recent years published a string of retro-noir books, including The Colorado Kid, by Stephen King, and Grifter’s Game, by Lawrence Block. (Fifty-to-One is the latest installment in the series.)

But it seems to me there’s also a political dynamic at play here. American filmgoers, for instance, are drawn to cowboy flicks in times of international crisis. (This happened during the Cold War, and again a couple years ago, as the Iraq War was intensifying. See 3:10 to Yuma, and the Assassination of Jesse James for further evidence.) When all the news is of doom and gloom and internecine warfare, we long for a modicum of unambiguous moral drama: a bad man and a noble man, and the fate of the world hanging in the balance.

Good noir is quite a bit more tangled than that, of course—the genre’s heroes tend to carouse and fight and dabble in extracurricular vice. But pulp writers never let the vice obscure a pure heart; we know in the end that the detective will solve the case, rescue the dame, and later contentedly smoke a cigar in a darkened office.

After all, what is a detective but a figure of allegory—a hero who can make sense of our topsy-turvy world, by reason and the occasional show of muscle? What is a detective but a deft negotiator—a George J. Mitchell in a rumpled fedora? We look eastward with dread: the tumult in Pakistan, the mess in Gaza, the explosions in Afghanistan. Then we pick up a noir novel, where a strong and savvy operator has all the clues in hand, and the end is always in sight.