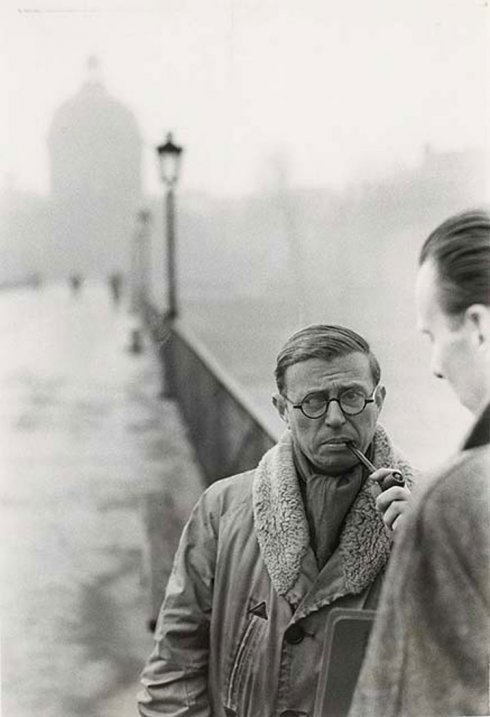

Jean-Paul Sartre in VQR

Jean-Paul Sartre, 1946. (Photograph by Henri Cartier-Bresson)

In October 1945, with the tumult of the Second World War and the repressive censorship of the Vichy regime newly ended, Jean-Paul Sartre founded a literary and political quarterly called Les Temps modernes (Modern Times). In his preface to the inaugural issue, Sartre derided writers who believed in pure literary art—calling Marcel Proust an “accomplice of bourgeois propaganda” and dismissing Gustave Flaubert as a “talented coupon clipper.” He argued against their notion of “art for art’s sake” and in favor of littérature engagée (“a literature of engagement”). We might wish to turn away from the events of the world, Sartre wrote, but “we have only this life to live, amid this war,” and writers who feel a greater obligation to craft than to community, who write for the ages rather than their historical moment, “have allowed their lives to be stolen from them by immortality.”

Sartre’s words ruffled feathers among the French literati, but he was still virtually unknown to English-speaking audiences. He had only gained a toehold with American readers that previous spring, when he was invited to give a pair of lectures to the French Department at Yale. The graduate students in French were so smitten that they requested a course on Existentialism. The class, the first in America to feature Sartre in the curriculum, was taught by professor Kenneth N. Douglas, who, in turn, began publishing a series of articles on Sartre in small magazines like Yale Review and French Review. In his essay “The Nature of Sartre’s Existentialism,” published in the Spring 1947 issue of VQR, Douglas wrote:

Existentialism is a crusade on behalf of forgotten man, of the man who feels, and thinks, and does, against man as an object to be tested for aptitude and achievement, tabulated on charts and reduced to a punch card, experimented upon, casually explained away, utilized, fired, junked, liquidated, cremated, or atomized. Sartre has begun to play his part, to write his part, in this project.

To accompany his piece, Douglas was asked by VQR editor Charlotte Kohler, who feared that Sartre would be unknown to her readers, to arrange for a translation of one of his recent essays.

Douglas selected “We Write for Our Own Time,” a response to the criticisms of his introduction to Les Temps modernes, for uncredited translation by Sylvia Glass. Like his introduction before it, Sartre’s new essay—published in French in Erasme in October 1946—was a manifesto for Existentialism and literature that speaks to its moment. The essay was, by turns, aphoristic and philosophically dense. “Art cannot be reduced to a dialogue with dead men and men as yet unborn,” Sartre writes in the opening paragraph. Later, he explains that urging writers to write for their own time does not mean they should “reflect it passively. It means that we must will to maintain it or change it; therefore, go beyond it toward the future; and it is this effort to change it which establishes us most deeply in it.”

Even with this potent statement of purpose, Kohler felt compelled to explain to readers that the author was “a leading exponent of the philosophy of existentialism” whose recent work had “aroused a good deal of controversy in Paris.” She noted, too, that having been taken

prisoner in the war by the Germans, he was released after eight months’ internment and assumed the chair of philosophy at the Lycée Condorcet in Paris. Besides his best-known philosophical work, “L’Etre et le Néant,” he has written many novels and plays of ideas. One of the latter has been presented in New York this year under the title “No Exit.”

Of the play, Douglas wrote: “The action takes place in Hell, and the thesis developed is that Hell contains no devils with pitchforks or cauldrons of boiling oils. ‘Hell is other people.’”

Yet, Douglas explained, Sartre’s ideas of intersubjectivity were neither so bleak nor so easily summarized:

Men live together. They need each other, in the first place, in order that they may remain alive. Beyond that, they need each other. For each of us seeks to know himself, and many aspects of ourselves can be seen only by others, we can learn of them only through others. Am I witty, aggressive, self-centered, sly, easily annoyed? The terms have little meaning for the castaway on a desert island. Nor can this information be obtained from creatures I am trying to debase to the level of objects, as slaves, “perfect” servants, members of “subject races.” My freedom requires theirs, and requires that they realize their freedom.

Seen in this light, Sartre was arguing not only that literature should serve the common good, but that it was immoral for writers to approach literature as a fundamentally personal act. Only by understanding and engaging the lives of others could we ever come to understand ourselves; only by valuing all people and all races—an indictment of Nazi Germany but also French imperialism in Algeria and Jim Crow laws in the American South—could we ever hope to find anything of universal value in our subjective view of the world.