The Gay Godfather of James Bond

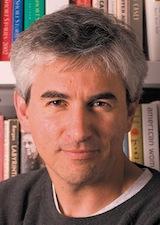

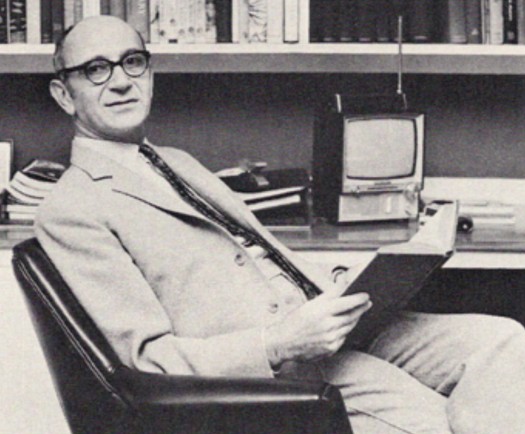

Born a hundred years ago today, the poet and critic Paul Dehn trained spies, won an Oscar and, notwithstanding his long, loving co-habitation with another man, helped create the epitome of 20th-century heterosexual virility—yet even Google all but asks, “Paul who?”

How could this be? What tastemakers did he offend? Did he throw a drink in Malcolm Cowley’s face, make a pass at Edmund Wilson? Hardly. His only crime was to excel at the art that dare not speak its name:

Paul Dehn was a screenwriter.

In addition to his great unsung original scripts, Dehn wrote or helped write the definitive James Bond picture (Goldfinger), two excellent John le Carré films (The Spy Who Came in From the Cold and The Deadly Affair), a virtual primer on how to translate an Agatha Christie novel to the screen (Murder on the Orient Express), and a fondly remembered adaptation of a certain derivative Elizabethan playwright (The Taming of the Shrew). He has credits on all four initial Planet of the Apes sequels, and won the Oscar for his very first screenplay, the widely influential Cold War suspense film Seven Days to Noon.

In the process, Dehn [as in “the melancholy …”] resurrected or reinvented at least three genres given up for dead at the time: the British mystery, the Shakespeare adaptation, and the spy film. He understood a thing or two about espionage, having refined and then practiced it with distinction in England’s Special Operations Executive during World War II. Yet the 100th anniversary of Dehn’s birth is passing today without the merest hiccup of notice.

In an upcoming issue of VQR, I hope to lay out some of the reasons that make Paul Dehn worth remembering not just on his centenary, and by a few film scholars, but generally, and by everybody interested in the authorship of their favorite movies. Dehn wasn’t the best screenwriter who ever lived. He wrote too few originals, and too often in collaboration, to claim for him anything of the kind. Nor was he the best author ever to approach film as an art form, rather than a form of slumming. That would be Graham Greene or perhaps Harold Pinter, the only (even half-time) screenwriter ever to win the Nobel Prize for literature. No, Dehn was merely very, very good. Just as important, he had a sensibility that withstood even the overbearing director’s attempts to flatten it.

I also hope to highlight at least a few plot turns in a life story that plays out, at times, like a corking good yarn. There will be holes aplenty, owing to the critically and criminally under-archived nature of almost every screenwriter’s work. (Anybody who knew Dehn is hereby encouraged to come forward before he fades from living memory.)

But beyond his own considerable merits, let Dehn’s story double as a kind of cenotaph marking the tomb of the unknown screenwriter. Behind him stands a legion of writers for whom, alive or dead, a hundred years can pass and no one lights a candle.

See you in print soon.